The Roaring Girl, Swan Theatre, Stratford-upon-Avon, review

Support truly

independent journalism

Our mission is to deliver unbiased, fact-based reporting that holds power to account and exposes the truth.

Whether $5 or $50, every contribution counts.

Support us to deliver journalism without an agenda.

Louise Thomas

Editor

We're used to heroines in Elizabethan and Jacobean plays who disguise themselves as boys for protection or in order to pursue the men they love. But once the barriers to marriage are surmounted, they discard these assumed identities. Not so the title character in The Roaring Girl, the 1611 city comedy by Dekker and Middleton. There's nothing covert about her cross-dressing nor does it have romantic designs. It's an open way of life and a calculated challenge to normative notions of gender and femininity.

The authors based Moll Cutpurse on Mary Frith, a notorious London underworld figure who wore men's clothes and smoked a pipe and may well have been the first English woman to perform on the stage in a public theatre.

There is evidence that, in male apparel, she played the lute and sang at the Fortune Theatre. Lucky the punters who saw her there in conjunction with her theatrical double who would, of course, multiplying the ironies, have been played by a male actor.

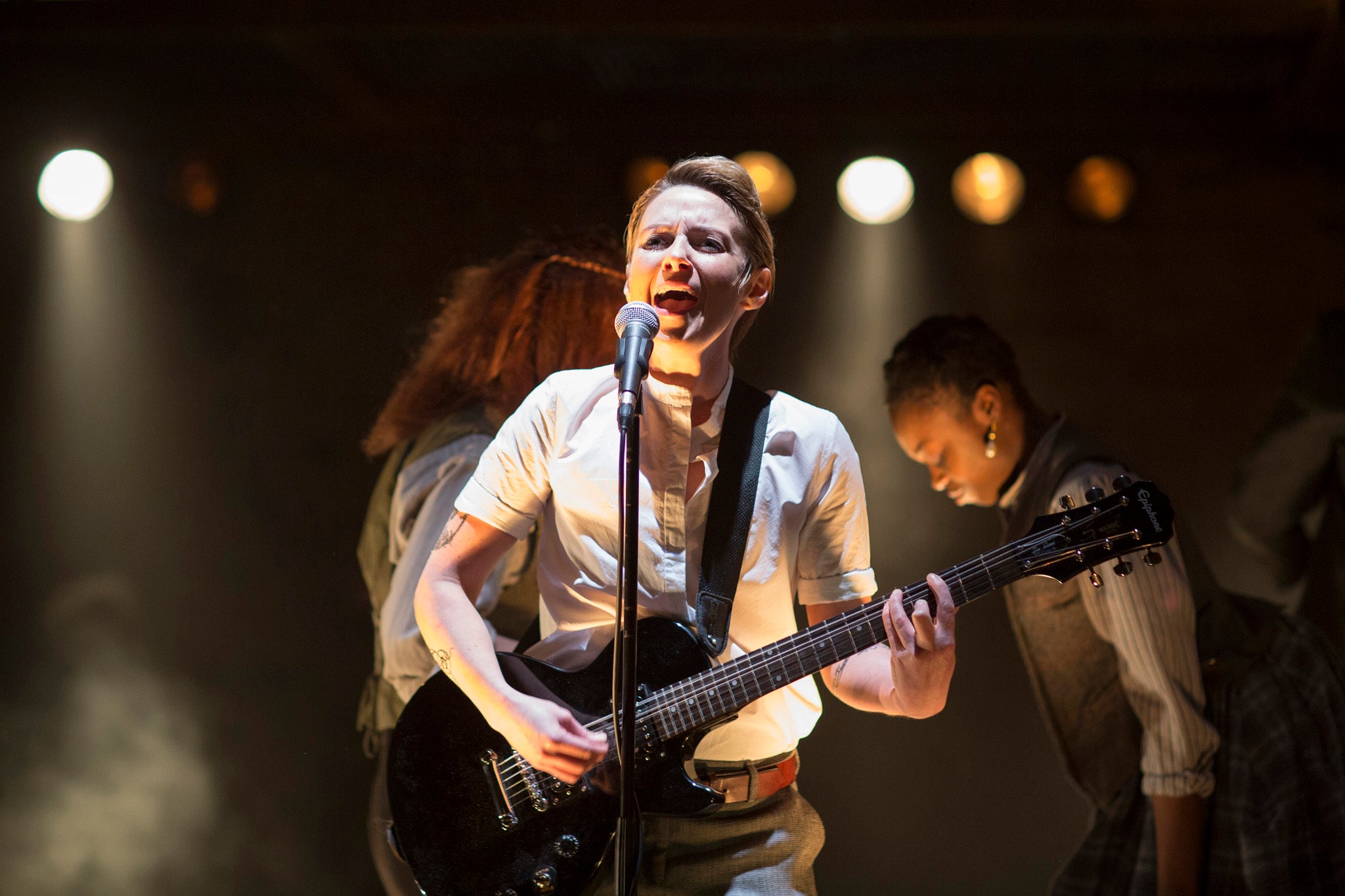

Launching the RSC's “Roaring Girls” season of plays with strong female leads, Jo Davies's vibrant production relocates the piece in the 1880s with the Jacobean gallants now check-suited on-the-make Victorian slickers and the knighted merchant aristocracy brandy-swilling white-tie-and-tails toffs. Lisa Dillon's utterly arresting Moll is a drop-dead super-cool maverick, her cock-of-the-walk swagger beautifully contained in its self-amused confidence.

She smokes with thumb and forefinger; she affects a thin maquillage moustache and little archipelagos of stubble. But she's not a wannabe man; in complete control of the confusing signals she sends out, she's a satirist of gender and its social construction. Dispensing with period authenticity, the production ramps up the sense of rebellious androgyny by turning her, for raucous bursts, into an exultantly defiant rock singer/guitarist who fronts a band of brass-playing fellow-cross-dressers and, at one point, swings on a chandelier.

This is good fun and it's a pleasure to watch the cool, witty contempt with which Dillon wipes the floor, in a sword-stick fight, with Laxton (Keir Charles), the slicker who presumes that she must be a whore: “I scorn to prostitute myself to a man/I that can prostitute a man to me”. But the modern slant which this staging gives to her transgressiveness has a paradoxical drawback.

It emphasises how Dekker and Middleton offer in Moll a rather sanitised portrait of Mary Frith. Belying her reputation for thievery and licentiousness, their heroine is a chaste beacon of honest dealing in a world riddled with sexual hypocrisy and greed. She will have no truck herself with marriage (which is “but a chopping and a changing, where a maiden loses one head and has a worse one in its place”) and yet is willing to play her part as pretend love-object in a comic intrigue that brings a courtship, stymied because of an inadequate dowry, to a conventionally happy conclusion.

The unsettlingly liminal allure of Dillon's performance and the gutsiness of the production (which ends in a very funny sartorial sandwich of bowler hats and bridal veils) might lead you to expect something more radical.

To 30 Sept; 0844 800 1110

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments