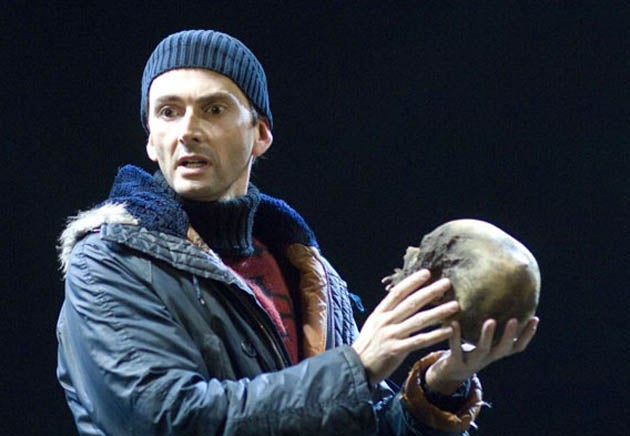

Hamlet, Courtyard Theatre, Stratford-upon-Avon

Doctor who? Tennant captivates as Hamlet

He's alienated, adrift in an inimical universe, and subject to bouts of existential depression and to fits of larky lunacy. He gives the impression of knowing more than he can possibly tell to other creatures. From time to time, he exhibits a penchant for sporting student scarves and he exudes the air of a brilliantly batty, eternal undergraduate. Yes, it's clear that Doctor Who must have been a key role model for young Hamlet. Perhaps the Tardis touched down in Elsinore during the troubled Dane's formative years.

You don't, though, need to resort to such desperately strained analogies in order to justify the casting of David Tennant as Shakespeare's most complex hero. Another doctor, Jonathan Miller, recently attacked the English theatre's "obsession with celebrity" – dismissing Tennant as "the man from Doctor Who" and castigating producers for their attachment to the "merely famous". It's an odd charge coming from a man who gave Joanna Lumley (not exactly media land's best kept secret) the leading part in his Sheffield revival last year of The Cherry Orchard.

Some of Miller's points are valid. Hollywood stars with scant stage experience are good only for box office (and not always for that). But he's way off the mark with Tennant, who is classically trained, with two earlier seasons at the RSC under his belt and the veteran of a number of roles that are sterling preparation for Hamlet, including a wittily edgy Romeo and a manically mordant Jimmy Porter, that latter-day Angry Young Man.

Besides, it's pure snobbery to suppose that Doctor Who fans and people who can appreciate Hamlet are mutually exclusive groups. This is proved by the audiences for Greg Doran's powerful modern-dress revival in which Tennant turns in an extremely captivating performance. It's a joy to see Stratford's vast Courtyard Theatre packed to the rafters and liberally sprinkled with children who remain rapt throughout. And the focusing effect of a booked-out house is intensified because of the huge wall of mirrored panels at the back of the long thrust stage. This reflects the audience and the chandeliered palace and allows for vivid special effects. In the closet scene, Hamlet shoots the eavesdropping Polonius with a revolver and the glass crazes into a huge, psychologically suggestive spider's web of cracks.

The production has plenty to offer Shakespeare aficionados and young first-timers, even if certain broad touches feel faintly gratuitous – such as taking the interval on an artificial cliffhanger with Hamlet's flick-knife suspended over Patrick Stewart's praying Claudius.

Tennant is adept at most aspects of the role but he excels when the prince becomes a prankish provocateur. A lanky live wire with a wry twist to the mouth and mocking brows, he puts on a thrillingly risky display of barbed levity and flippant sarcasm. Even when strapped to a swivel office chair by Claudius's henchmen, this Hamlet manages to improvise a subversive joke that insults his uncle. He whizzes away to his enforced exile on its castors with the sardonically exuberant cry of "Come, for England, wheeeee!!". Barefoot in a DJ, he can hardly contain his baleful delight before the play-within-the-play and, in its chaotic aftermath, he slouches over the throne, his suspicions triumphantly confirmed, mangling "Three Blind Mice" on a recorder and with the crown resting on his head at a rakish angle.

Tennant gives a further serrated edge to this confrontational comedy through the variety of voices he deploys. There's the spoof bored sing-song for the politically incendiary quibble: "The body is with the king, but the king is not with the body. The king is a thing –" or a doddery, toothless old man delivery when he twits Polonius with the idea that there's nothing he would more willingly part with than Polonius's company "except my life, except my life, except my life".

This side of his portrayal is of a piece with a production that finds many opportunities for queasy black humour. Mariah Gale's haunting Ophelia, nobody's fool at the start, seems unsurprised to fish out contraceptives from her brother's suitcase. Polonius's sheer purblind irresponsibility as a father is hilariously and horridly emphasised in Oliver Ford Davies's superb performance by his habit of drifting off into donnishly absent-minded world of his own – especially when making crucial and intrusive decisions about his children. The grimmest gag of all comes in the final hectic scene of slaughter. This Hamlet doesn't need to force the poisoned wine down the throat of Patrick Stewart's creepily self-possessed Claudius. Handed the goblet, Stewart raises it in a cynical salute to his troublesome nephew before downing its contents. It's diabolical cheek: a gesture of "good health" to a man who has only minutes to live because of the drinker's own machinations.

I rate Tennant very highly, but I wouldn't put him in the absolute front rank of contemporary Hamlets, a category which, for me, includes Simon Russell Beale, Mark Rylance and Stephen Dillane. Or not yet, at any rate. The performance has time to grow. This actor has most of what it takes: the braininess, the breadth of spirit, the reckless irony, the bamboozling banter, the sense of layered depth. He can produce moments of sudden stillness when he seems to be dazed by the vortex of meditation. After ecstasies of anger in the closet scene, he can turn into a deeply affecting lost boy kneeling by Gertrude's bedside and trying to reconnect the primal family circuit. But while this Prince is able to reach out and touch his father's Ghost (Patrick Stewart, doubling), his mother can neither see nor feel him.

So what's missing? Well, the part of Hamlet constitutes a special case. However hard you analyse his behaviour and motivations, this character remains to some degree a tantalising mystery. He's not exactly a Rorschach blot – though a critic has astutely pointed out that the idea of one is anticipated in the cloud that Hamlet forces Polonius to agree looks like a camel, a weasel and a whale. But it's why the role is particularly revealing about the personality of the actor playing it. (You don't have to be the poet Coleridge to think "I have a smack of Hamlet, myself, if I may say so".) In the soliloquies, the finest performers seem to be, partly, laying bare their own souls to us, too and laying us bare to ourselves. At the moment, that strange double-feeling of exposure and spiritual connection is not as strong here as one could wish here.

There may be technical reasons for this. It's a pity, for example, that Tennant is using an RP accent rather that his natural incisive Scots lilt that might promote greater intimacy of rapport. One remembers how Fiona Shaw's acting was liberated when she started to speak in her native Irish tones. And then there are some distancing and questionable directorial decisions. This is not an account of the tragedy that plays down the politics (Stewart's low-key, canny portrayal demonstrates that Claudius is the subtlest mind in the play after Hamlet) but the production ends with the arrival of a burly Fortinbras who is left standing mute in the doorway. By axeing Horatio's speech of explanation ("so shall you hear/Of carnal, bloody and unnatural acts") which reduces the revolutionary drama we have seen to the dimensions of a standard gory revenge play, the production unwisely relieves the audience of the exquisite pain of feeling that we know this hero, who has poured out his soul for us, better than any of the survivors.

I expect that by the time the production reaches London, these problems will have sorted themselves out. Meanwhile, this is a stirring and impressive theatrical event. The RSC is not allowing Tennant to sign sci-fi memorabilia – so you can leave your reproduction sonic screwdriver at home. You never know, though, this Hamlet may switch some Shakespeare buffs on to Doctor Who.

Paul Taylor's top three contemporary Hamlets

Jonathan Pryce, Royal Court, 1980

There was a singular departure from tradition in Richard Eyre's powerful production. Jonathan Pryce's splendidly dangerous Prince internalised his father's ghost, hawking up its speeches as though the victim of Oedipal possession.

Mark Rylance, Stratford, 1988

For many, the supreme Hamlet of our times. It's a huge tribute to his performance that when the production visited Broadmoor, one of the inmates accosted Rylance at the end and marvelled: "You really are mad, aren't you?" But this bottom-baring Prince in soiled pyjamas also gave you the piercing sense of great, searching soul snuffed out before its prime.

Simon Russell Beale, National, 2000

Russell Beale portrayed Hamlet in a brilliant performance that combined scholarly ironic wit and a spiritual mellowness and aching regret that were attributed to grief at the death of his own mother.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies