Ripping yarns: Enid Blyton's secret life

Enid Blyton's life was not always as jolly as her stories. As a new BBC biopic is announced, John Walsh reveals the author's darker side

How positively ripping. Shooting has just started, in London and Surrey, for a movie about the life of Enid Blyton. And golly gosh, they've persuaded Helena Bonham Carter to play the children's writer in a BBC4 production, to be broadcast in the autumn. Helena is such a brick...

It doesn't, at first sight, seem terribly promising as biopics go. Blyton's life is not a thing of gripping drama, vivid incident and intellectual ferment. Most of it consisted in her sitting at a desk, knocking off 10,000 words a day and publishing 753 books over 45 years: a torrent of children's novels, stories, poems, the long sagas of the Secret Seven and the Famous Five, the Noddy books, the Angela Brazil-derived, girls-at-school books about Malory Towers and St Clare's, the tales of magic, circuses, farms and nature. They sold 600 million copies around the world and made her extremely rich and famous.

Her works defined escapism for the under-12s. She told stories of children escaping from mad or eccentric aunts and uncles to explore somewhere more exciting; children whose parents were unaccountably away for whole weekends, allowing them to roam, unchecked, through haunts of smugglers, kidnappers and dodgy foreigners – whom they would outsmart at the climax of the story and deliver to the hands of the local constabulary, before being rewarded with platefuls of plum cake and inevitably, lashing of ginger beer.

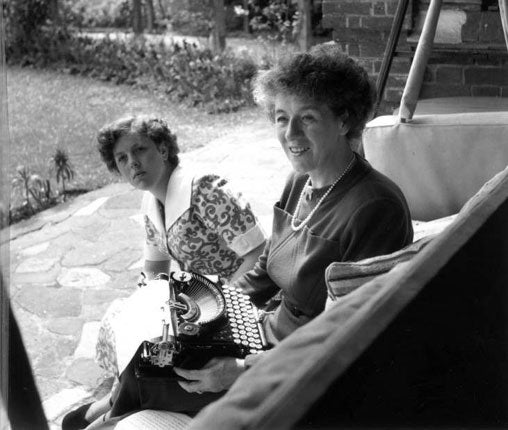

Bonham Carter's fans may enjoy watching her pound a typewriter, but might the excitement pall after a while? Blyton's home life in the 1930s had a picture-perfect quality. She lived in houses called Old Thatch – a fairy-tale cottage, with a lychgate and several pets – and Green Hedges, a mock-Tudor house in Beaconsfield with a nursery, nannies, crumpets for tea, Bimbo the cat and Topsy the dog. The image Blyton carefully projected to the outside world, of an ideal family life filled with benevolence, love and small animals, wouldn't electrify a modern TV audience.

Thank goodness, then, that her life was far from the domestic millpond she wished the world to see. Her neighbours at Green Hedges recalled how Blyton used to complain about the fearful racket made by children playing. She was frosty, distant and unkind to her younger daughter Imogen, who called her "arrogant, insecure, pretentious and without a trace of maternal instinct", and told Gyles Brandreth, "Her approach to life was quite childlike, and she could also sometimes be quite spiteful like a teenager." There was clear favouritism in the way she privileged and rewarded her elder daughter Gillian over her younger.

Blyton's first husband, Hugh, called her "Little Bunny". They were married for 19 years but, as Enid's career took off in the 1930s, Hugh grew increasingly depressed and took to nightly drinking sessions in his cellar. Enid ceased writing long enough to have adulterous affairs. The marriage deteriorated and Hugh moved out. According to the biographer Duncan McLaren, she mocked him in later adventure stories (such as The Mystery of the Burnt Cottage) as the clueless cop, PC Theophilus Goon.

At the time, she was editing and writing for a magazine she'd started called Sunny Stories. For each issue, she contributed tales and autobiographical notes, which would sometimes refer en passant to "my husband". After a bitter divorce, she remarried with startling speed: he was a surgeon called Kenneth Darrell Waters with whom, apparently, she had a properly fulfilling sex life at last. But no ripple of concern, no tiny hint of trouble, alerted readers of Sunny Stories that the person referred to as "my husband" in 1944 was a completely different model from the one in 1941.

They might have been surprised by Blyton's flightiness. A BBC documentary called Secret Lives: Enid Blyton revealed that visitors to her charming rustic retreats could arrive to find her playing tennis naked. It also hinted strongly that Blyton's intense relationship with Dorothy Richards, her children's nanny, was sexually driven. Along with her sensuous side was a streak of implacable stubbornness and cruelty. When her first husband Hugh married again – as she herself had remarried – Enid was so furious she banned her daughters from seeing their father ever again, no matter how much they (and Hugh) begged to be allowed.

Many of her authorial obsessions can be traced to her father, who left her mother when Enid was 12. She effectively seized up, physically. Later when she consulted a gynaecologist about her failure to conceive, she was diagnosed as having an "immature uterus". She needed special surgery and hormone treatment before she could have children. She remained, in other words, a little girl, stuck in the paraphernalia of childhood, suspended in a world of picnics, secret-society codes, madcap pals and midnight feasts at school – a gigantic, prepubescent comfort blanket.

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 day

New subscribers only. £9.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled.

ADVERTISEMENT. If you sign up to this service we will earn commission. This revenue helps to fund journalism across The Independent.

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 day

New subscribers only. £9.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled.

ADVERTISEMENT. If you sign up to this service we will earn commission. This revenue helps to fund journalism across The Independent.

It's often been remarked that, although the Famous Five are technically teenagers, they appear to suffer no hormonal promptings. Georgina ("George"), the one who hates being a girl, is 12 when we first meet her; through 21 adventures, over three or four years, she never develops breasts or mellows her attitude. Barbara Stone, Blyton's biographer, suggested that George was modelled on the young Enid, constantly rebellious, hot-tempered and pugnacious. She had, it seems, a considerable talent for concealment and silence. When her parents split up, she told nobody, not even her best friend. Her relationship with her mother was so bitter that, when she left home and found a job, she let her new colleagues assume her mother was dead. When her mother finally died, Blyton refused to attend the funeral.

So why is Enid Blyton's industrious shade enjoying a renaissance? The signs are unmistakable... Apart from the BBC extravaganza, Disney UK has green-lit a new, animated feature called Famous 5: On the Case, in which the children of the original Five (even the dog) enjoy some new adventures. Amazingly, the creator of Noddy and those malevolent muggers The Three Golliwogs, was named Britain's best-loved author in a poll for the Costa Awards. Twenty "in the style of" pastiches of Blyton classics, from the Five to Malory Towers, have been commissioned by Chorion, the Blyton estate, which comprehensively edited her works in the 1980s and 1990s to remove thousands of "offensive" racist and sexist words, phrases and references. Chorion reports a striking hike of sales (up to £7.5m) in the past 12 months.

Readers looking to explain her revival in popularity point to the recent rash of "Dangerous" books for boys and girls – invitations to connect with a world of outdoor fun, exploring rivers and old houses and mucking about with your pals all day long. As The Dangerous Book for Boys taught children how to tie knots and whistle with two fingers, Blyton's repetitive, one-dimensional adventures tell you, inter alia, how to escape from a locked room and how to write invisible messages. The stories, however flatly written, are about self-reliance and self-empowerment, in which children perform implausibly brave and superhuman feats, solve puzzles, fight crime and help police, while escaping from their parents. They endure because the quality of obsessive self-renewal in Enid Blyton's character, constantly escaping from her own past, comes strongly through.

Will Helena Bonham Carter make a convincing screen Enid? Absolutely. Look at the scene in her debut movie, Merchant-Ivory's A Room with a View, when, playing the headstrong teenager Lucy Honeychurch, she bashes merry hell out of the family piano to express her pent-up rage. It's George from the Famous Five to the life. Her years of being crammed into corsets should give her insights into the minds of Darrell and Co, the rules-bound teens at Malory Towers. Her role as the tough but weary Jewish mother in Paul Weiland's Sixty Six showed that her range could extend to take on the everyday traumas of marriage. And her readiness to remove her kit on screen, as she does (quite unnecessarily, but nobody's ever complained) at the end of The Wings of the Dove is good news for all furtive voyeurs who've always longer to visit one of Enid Blyton's unusual tennis matches. Wizard!

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks