Absence of War, theatre review: Revival of David Hare's play is a history lesson for Ed Miliband - forget the economy, unleash ideals

It makes you pointlessly wonder whether Neil Kinnock, unbound and 20 years younger, wouldn't have been a pretty good fit for 2015

The general election has just been called, and the Labour leader is confronted by his staff with the long-planned daily “grid”: Tuesday, health; Wednesday, education; Thursday, health; Friday, health. “Lord, do we ever do anything else?” he asks.

“Health is the lever,” his chief of staff replies firmly. “Health is the knife that’s going to detach voters from their primary loyalties and get them churning.”

Shouldn’t there be something on the economy, asks the leader’s press secretary. No, says her boss. “What he mustn’t do is… remind people that when he’s elected he’s going to be in charge of their money.”

If nothing else, David Hare’s 22-year-old Absence of War, playing in a gripping new revival at Sheffield’s Crucible Theatre, is a topical reminder that there’s nothing new either about Labour weaponising the NHS or being under continuous onslaught from its manifold enemies on its fitness to run the economy. But of course it’s about much more than that: not only Labour’s chronic inner conflict between principle and electability, but the often dismal nature of modern politics itself.

For anyone who observed the 1992 election close up, let alone saw the play a year later, this production by Jeremy Herrin brings the memories flooding back. Reece Dinsdale is not the late John Thaw whose performance as George Jones, loosely but unmistakeably based on Neil Kinnock, electrified National Theatre audiences two decades ago. But he captures the humanity, inner decency – and humour – of the play’s tragic hero, a man caught in what Hare would later call Kinnock’s “haunting situation” of having honourably decided “that the party could not be elected unless he was willing to make a pact with respectability – a quality Neil himself called a ‘fourth-division virtue’”. And then went down to defeat.

According to one of his closest colleagues at the time, Kinnock, an avid theatregoer who had allowed Hare his ringside seat in the 1992 campaign, was seriously hurt by the play. In a way he shouldn’t have been. The almost unbearable scene in which Jones loses it while making a crucial campaign speech didn’t happen in real life.

Hare, moreover, understood Kinnock’s historic contribution; far more than Tony Blair, he did the heavy lifting to modernise Labour by ditching its anti-European and unilateralist defence policies. And he did, as Jones/Kinnock says in the play, hand the party “in good order” to his shadow Chancellor and successor Malcolm Pryce/John Smith. Good enough to ensure a Smith victory in 1997, but for his tragic death in 1994.

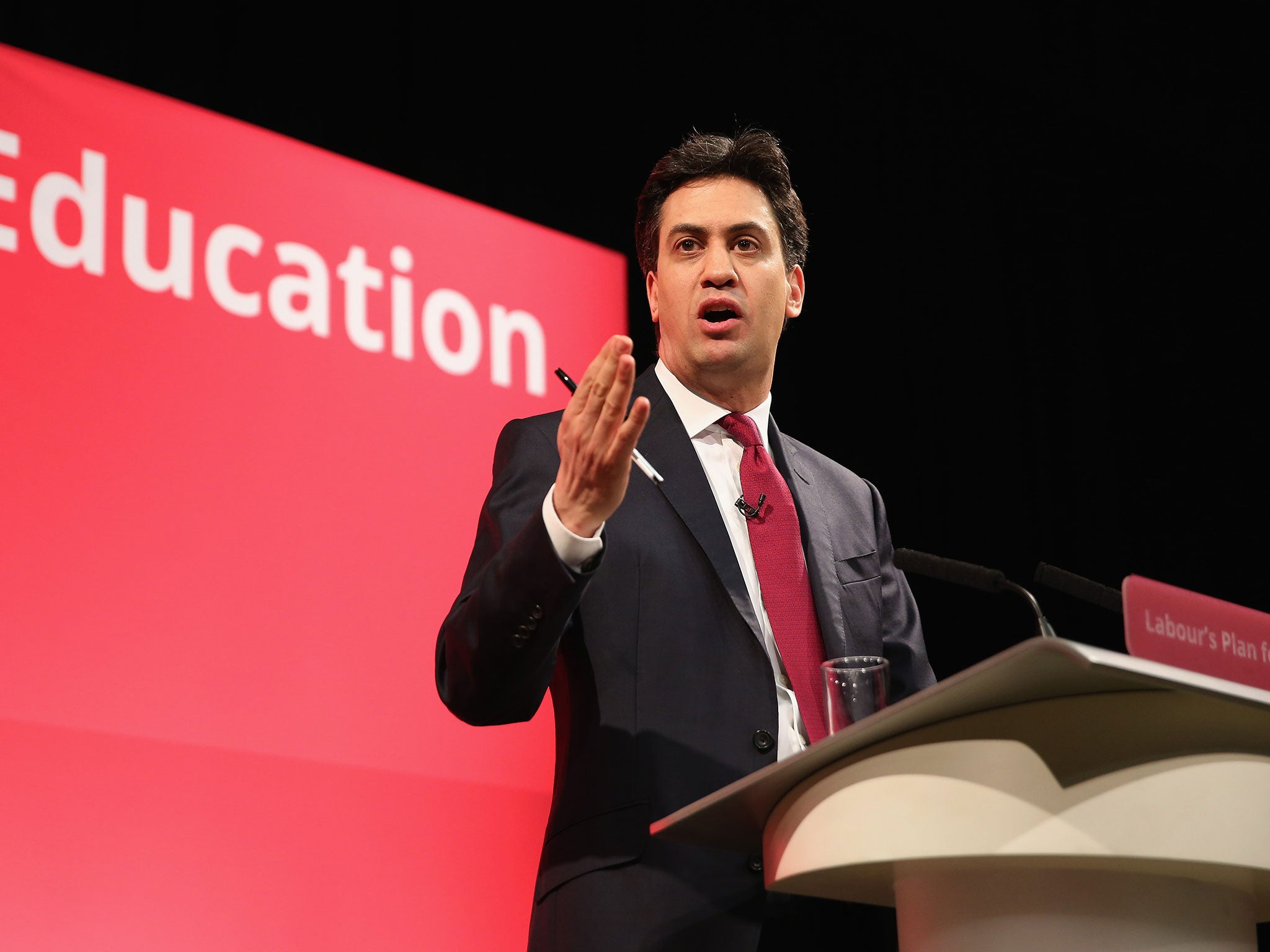

If some of Ed Miliband’s staff sneak off to catch the play during its national tour, what similarities and differences will they find? The torments of a hostile Tory press. The need to rein in your economic instincts to reassure floating voters. Rumblings from the leader’s colleagues: “He’s much too disloyal to be openly disloyal,” his young lieutenant Andrew says about one.

In at least one respect, though, Miliband could find it easier. “Never use the word ‘equality’,” says Hare’s election war book. “The preferred word is fairness.” Which is an accurate reminder that the “E-word”, though once an ideological cornerstone of Labour’s social democratic right, was banned by its leaders for a generation. Yet now that even the Davos-heavy mob worry aloud about economic and social inequality, isn’t it ready to become respectable again?

In a pivotal scene, the leader’s advisers, scenting imminent defeat, hold a crisis meeting to argue about whether he should show the public more of his passion and the “articulate, funny, authoritative” private self, casting off the relentlessly on-message straitjacket they have put him in.

“That’s your talent,” insists his deputy (which it was; Kinnock in his day was a brilliant orator). “Get up on Monday and say what you want. Say it without thinking… They want to see you take the whole rotten thing on.”

Recent research, especially in the US, suggests that voters are much more persuaded by visceral, emotional argument than by fact or reasoned analysis. Which may help to explain the appeal of a Nigel Farage or Alex Salmond, much stronger on the first than the second (even if the great speeches combine both).

The two men’s personal politics are close enough for Miliband to have been Kinnock’s favoured leadership candidate in 2010. But there’s less sign that Miliband is suppressing an inner firebrand as Kinnock was obliged to in 1992, losing much of his charisma and humour in the process. Watching Hare’s play, you can’t help pointlessly wondering whether Kinnock, unbound and 20 years younger, wouldn’t have been a pretty good fit for 2015.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments