Wall Street of the empire

THE ARTICLES ON THESE PAGES ARE PRODUCED BY CHINA DAILY, WHICH TAKES SOLE RESPONSIBILITY FOR THE CONTENTS

A UNESCO world heritage site today, the ancient town of Pingyao in Shanxi province formed the economic backbone of China during the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911). The town housed the country’s first piaohao (money exchange house) that bankrolled the empire when all bookkeeping was on paper and the only way to crunch numbers involved the abacus.

In 19th-century imperial China, business-savvy merchants from Shanxi were making their presence felt in Japan and Korea in the east, Russia in the north and other countries in the south. They had to rely on security guards when transferring their financial wealth, measured in gold and silver, from one place to another. The method was highly risky and led to the inception of the piaohao.

The bank of Rishengchang, which means “sunrise prosperity”, was established in 1823 and became the prototype of China’s early financial system, offering remittance services and loans, and accepting deposits. It even boasted a high-capacity underground vault.

At its peak, the Rishengchang bank had more than 30 branches across the country, with business expanding overseas and reaching as far as Europe and the United States. More than a century later, in 1932, the exchange house halted its operations, but its preserved antiquity on public display today continues to fascinate all and sundry.

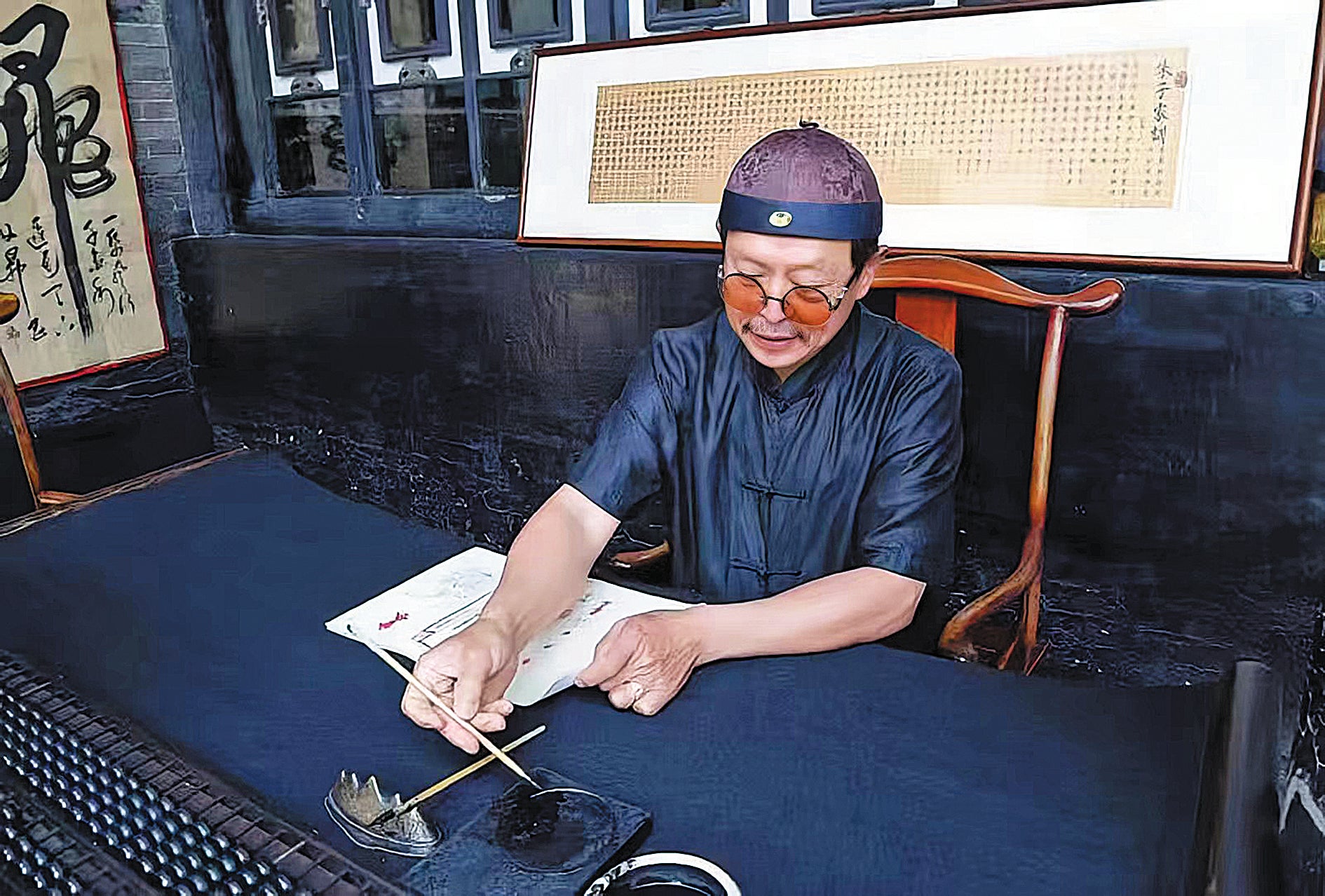

The erstwhile Rishengchang building was traditional in style, comprising halls and open courtyards. Jia Weixing, a museum guide, sits in traditional costume at a desk in a corner of a courtyard, which is now a museum.

For a decade, it has been Jia’s job to jot down the name, address, “silver exchange” and other details of visitors on a yellow tinted bill, which is then folded neatly into an envelope, in a re-enactment of how serious transactions were conducted 200 years ago.

“The idea is to show people how banking was done in the past. I love the piaohao culture of Pingyao. As we travel back in time, I love playing my part, writing a few ‘bank drafts’ to entertain visitors from across the country,” Jia says.

In his book Chinese Currency and Banking, published in 1915, Indian scholar Srinivas Ram Wagel wrote that the modern bill of exchange and discount methods were first proposed by the draft bank in Shanxi. People didn’t need to carry around silver anymore, he wrote, as the bill of exchange from Pingyao could not be counterfeited.

According to Jia, there were at least five marks on the bill of exchange to guarantee authenticity, just like patterns on currency notes today. There were seals and handwriting proofs. The Chinese characters for Rishengchang were printed as watermarks on four corners of the bill for added authentication.

“The piaohao also encrypted its bills with codes made up of Chinese characters, which were changed on a regular basis to enhance security,” Jia says.

The Rishengchang museum today preserves the only original bill of exchange from the past. It was these bills that allowed the exchange house to control more than half of the Chinese economy for a century.

The rise of modern banks after 1910 began to eat into the market share of the Rishengchang piaohao. “Their operation models were more advanced, and the big banks had foreign capital support, too,” says Li Chao, a member of the museum staff.

Also, the exchange house depended heavily on the Qing administration, which was overthrown after Xinhai Revolution, launched by Sun Yat-sen in 1911.

“Boom turned into bust and the piaohao was eventually replaced,” says Li.

In 1956, whatever was left of the Rishengchang building became the office of Pingyao’s supply and marketing co-operative. Major changes weren’t made; money was spent only on fixing some doors, windows and walls. The co-operative made way for the museum in 1995. The move was part of the protection and development strategy for Pingyao, and the Rishengchang began welcoming guests who wanted to learn about its remarkable history.

Peng Ke’er contributed to the story

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks