How a decorative shrub introduced by the British to India is now threatening tiger habitats

50 years of Project Tiger: In the first part of a series exploring India’s relationship with its national animal, wildlife experts tell Maroosha Muzaffar about the threat posed by this innocent-looking ornamental plant

More than 200 years ago, an innocuous-looking ornamental shrub was brought to India from Central America to adorn the gardens of its British colonial rulers. It was deceptively beautiful, its flowers changed colour with age, turning white, yellow, orange and pink. But within 50 years of its introduction, something menacing started happening: the plant spread from hedgerows and gardens and started killing native plants in its vicinity.

Lantana camara is now considered one of the worst invasive plants in the world – millions of hectares of forest across the globe have been taken over by this flowering shrub. In India, a 2020 study found that 44 per cent of forests were experiencing lantana invasion, contributing to the deterioration of forest ecosystems and threatening the habitat of the country’s majestic apex predator – the tiger.

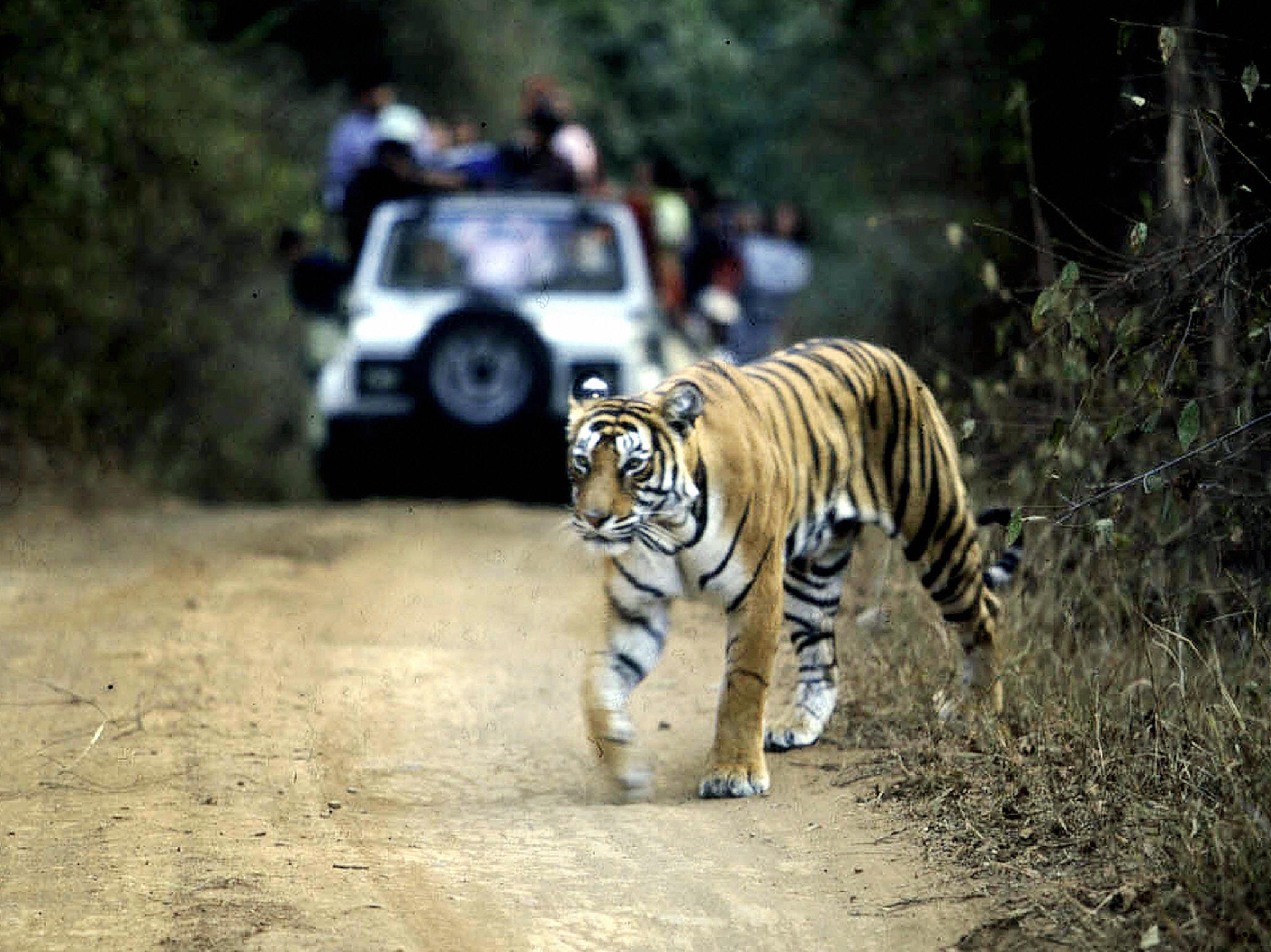

India is this month marking the 50th anniversary of Project Tiger, the initiative to provide safe havens for a species hunted to the brink of extinction. This weekend, the latest tiger census figures are expected to show numbers have leapt from 2,967 in 2018 to more than 3,500 individuals across 53 reserves.

Tigers are highly territorial and an individual can claim up to 150 square kilometres in which to hunt, making habitat loss due to invasive species like lantana a serious threat to the future expansion of tiger numbers in India. Ninad Avinash Mungi who has extensively studied lantana camara and is the lead author of the 2020 study, connects the dots. “These invasions are an important and fragile part of the tiger conservation story” in India, he says.

“It [the invasion of lantanain forests] has dire consequences. They outcompete native plants and grasses that herbivores like spotted deer and barking deer usually eat. These are the plants that are severely impacted by invasive plants.”

Mungi explains that the leaves and roots of lantana have a chemical that kills other plants in its vicinity once it comes into contact with the ground, leading to the depletion of plant diversity in the forest. Deer will not eat the lantana themselves, put off by its strong-smelling flowers and rough, jagged leaves.

As lantana takes over a forest and the deer’s preferred forage plants disappear, these herbivores are forced to look elsewhere for food. Official reports have warned of this decline, such as one recording losses of cheetal [spotted deer] in Bandipur Tiger Reserve in Karnataka due to a “paucity of quality forage and abundance of lantana camara”.

These deer are the primary prey animals for tigers – so they follow suit and move away too. This dynamic is being seen across India and can happen quickly: experts say that if the lantana invasion is not tackled soon, then within the next few decades tiger numbers will plateau and ultimately start to fall.

Rajat Rastogi, a researcher who has studied the invasion of lantana in Kanha Tiger Reserve in Madhya Pradesh, central India, says that the problem is pressing. In a study published in January this year in the journal Forest Ecology and Management by the Wildlife Institute of India, he says that invasive species threaten to “cause a future decline of herbivores, which are an important food resource for charismatic carnivores in these ecosystems”.

Rastogi tells The Independent that the problem is more complex than it seems, and that the presence of lantana in the forest may actually briefly make life easier for tigers before it affects populations negatively.

He explains that in forests dense with lantana shrubs, deer and other herbivores have to invest more time foraging for vegetation they can actually eat. “When they’re searching for food, there’s less time that they can be vigilant for other animals,” he says, making them easy prey for tigers.

“On a tiger reserve level, we’ll see that the carnivore’s health will become better because they are getting food easily. And the herbivores’ health will decline,” Rastogi says.

It is only in the medium term, over the next 10 to 20 years, that tiger numbers will also decline “because now there is no food available [for them]”, Rastogi explains. This vision of the future for India’s tiger reserves will become irreversible, he emphasises, if lantana is not actively removed from forests and replaced with native plant species.

Some scientists outside the field of tiger conversation celebrate the contributions of lantana to forests’ green cover and say the flowering shrubs are a boon to the diversity of both bird and butterfly species.

However, experts like Dr Geetha Ramaswami, who has studied lantana at Mudumalai Tiger Reserve in Tamil Nadu in south India and currently leads the SeasonWatch project at the Nature Conservation Foundation, says her research suggests otherwise.

She was intrigued by these invasive plants because “they have become successful at places where they don’t have an evolutionary history”. She tells The Independent that her research found how lantana doesn’t just increase green cover, but “fundamentally” replaces native species with a monoculture of shrubs.

“Our conclusion was that years down the line, the lantana invasion fundamentally changes how a forest will look,” she warns.

Forest officials are aware of the problem, and both state governments and the central administration in Delhi allocate funds for the removal of lantana and other invasive species from national parks every year.

But the work is labour-intensive and costly: according to rough estimates, the central government spends between Rs 80,000 to 120,000 (about £800 to £1,200) to clear a single hectare of dense shrubbery. To prevent lantana springing back, these interventions have to be repeated regularly over at least a three-year period.

And, for many experts, these efforts barely scratch the surface of the problem. Tarsh Thekaekara has mapped lantana invasion in forests across south India, and says the amount that state governments in the region spend on the removal of invasive species is “absolutely useless”.

He says that the removal of lantana from 30,000 hectares in Mudumalai National Park alone would cost an estimated Rs 3bn (about £30m). “But the [Tamil Nadu] government gives Rs 5m (about £50,000),” he says.

What little effort is made is also not done in a sustainable way, he says. Cleared forests are not then monitored, meaning lantana simply grows back. It’s an issue that has left many conservationists frustrated with the government’s approach, which typically involves manually cutting and burning lantana shrubs or, in extreme cases, sending in JCB diggers to uproot entire swathes of forest.

But there is another way, one prioneered over 15 years ago by Delhi University’s Professor CR Babu. He and a team of students had remarkable success in a pilot at the Corbett Tiger Reserve in Uttarakhand using the “cut rootstock” method. It requires simply making a small cut just below the soil level and then uprooting the plant and leaving it upside down.

“We did the experiment back then in the buffer area of Jhirna, Lal Dhang and Dhikala zones [in Corbett Tiger Reserve] that had been invaded by massive lantana growth,” says Prof Babu. Restoring the forest area also led to the return of rich wildlife – and in turn, better tiger sightings.

Today, several state governments employ Prof Babu’s “cut rootstock method” to tackle the problem in forests and tiger reserves. In Bandipur Tiger Reserve in Karnataka, southern India, an ecological restoration non-profit called Junglescapes has restored biodiversity in more than 1,200 hectares of lantana invaded forests using Prof Babu’s method.

Junglescapes’ Ramesh Venkataraman says lantana is not only a problem that “can hasten the depletion of animal species”, but one that can also leave the forest more vulnerable to wildfires. He says that a huge fire in 2019 at Bandipur destroyed more than 15,400 acres of forests and was later attributed to the area’s massive invasion of the shrub.

The Independent contacted several members of the National Tiger Conservation Authority [NTCA] with questions about the deterioration of tiger habitat and any remedial measures being taken by the government, but did not receive a response.

The problem is urgent, many believe. Mungi says that since his last study, the spread of lantana has only increased and he estimates that more than 60 per cent of forests may now be impacted.

Rastogi also sounds the alarm, and says that lantana is not the only invasive species of concern. He says that while there is more focus on lantana, other invasive shrub species like Ageratum conyzoides and Pogostemon benghalensis have started wreaking havoc on the biodiversity of tiger habitats.

Over the years, efforts have been made across the country to find uses for the lantana plant. The Ashoka Trust for Research in Ecology and the Environment [ATREE] runs “Lantana Craft Centres”, where they train local artisans to create furniture and other products from the removed shrubs. Another group, the Shola Trust in southern India, creates sculptures of elephants from removed lantana shrubs and takes them around as art exhibits.

Thekaekara believes this could be the key to solving the crisis – it is only when there are economic uses for the plant that its removal will become a priority. He criticises the NTCA for not giving clear instructions about the removal of lantana for commercial purposes by the general public – strictly speaking, this would be a breach of the Wildlife Protection Law, which bans any kind of commercial activity inside a tiger reserve.

Venkataraman says that ultimately the challenge of beating lantana “needs a very strategic and holistic approach, with coordination across state boundaries”.

“We are dealing with a very smart adversary,” he adds.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks