What does Exxon’s exit from Russia mean for the climate?

Major oil companies like Exxon may be leaving, but demand for fossil fuels won’t go away unless government takes action, Josh Marcus writes

There’s an old expression: in the oil and gas business, you need to run to stand still. New investments need to be made. Wells need to be drilled. As oil is pumped over time, pressure underground decreases, so more pressure becomes necessary just to maintain the status quo.

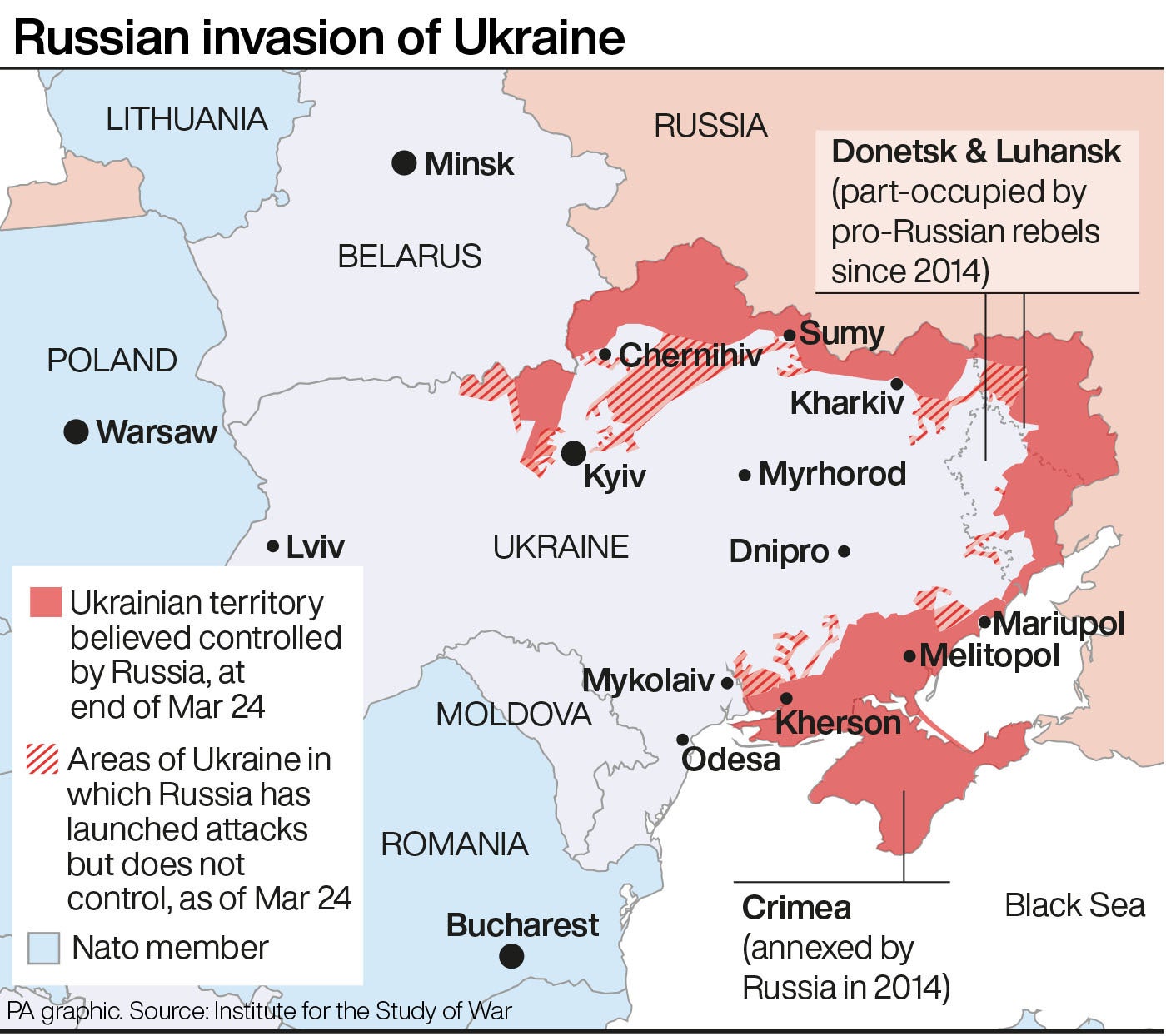

The biggest players in the oil business right now are indeed running – from Russia, as its brutal invasion of Ukraine continues.

Since the end of February, energy companies like BP, Shell, Equinor, and ExxonMobil, the largest oil company in the US, have all announced plans to cease major operations in Russia for the foreseeable future in protest over the Ukraine war, leaving tens of billions of dollars of business behind.

Exxon’s Russian operations alone are worth an estimated $4bn, including its management of the Sakhalin-1 project, a sprawling multinational oil and gas development in the frigid waters north of Japan.

“ExxonMobil supports the people of Ukraine as they seek to defend their freedom and determine their own future as a nation,” read a company statement on 1 March. “We deplore Russia’s military action that violates the territorial integrity of Ukraine and endangers its people. We are deeply saddened by the loss of innocent lives and support the strong international response.”

On the one hand, according to experts, the decision of firms like Exxon and others to leave Russia is a watershed moment in corporate accountability, a sign that even the biggest businesses in the world are willing, under the right circumstances, to put aside profits and take a moral stand.

On the other, for all the reshuffling that’s now taking place in the global oil supply, companies and governments may use this moment of transition to double down on fossil fuel investment, even as the latest United Nations IPCC climate report warns that any pause in efforts to cut greenhouse gas emissions means the planet “will miss a brief and rapidly closing window to secure a liveable future”.

Taking a closer look at Exxon and the American energy response to the Ukraine war reveals that for all that is changing, US climate priorities are largely standing still.

It cannot be overstated just how big of a deal oil, and marquee international oil projects like Sakhalin, are to Russia, where fossil fuel revenues supply about 40 per cent of the budget. The Sakhalin complex, which began production in 2005, is one of the largest sites of foreign direct investment in Russian history. The Russian state oil company, Rosneft, has a 20 per cent stake in the project.

Exxon’s involvement in Sakhalin was negotiated by Rex Tillerson, an oil executive who later became the Trump administration’s Secretary of State.

Exxon has weathered past crises like Russia’s annexation of Crimea, and has maintained ties to other corrupt regimes, like that of Equatorial Guinea, for the sake of ongoing projects. But the Ukraine invasion was simply one step too far for the oil major.

On a symbolic and domestic level, a US company like Exxon leaving Russia and Sakhalin behind is a massive development, says Professor Yan Anthea Zhang, a foreign direct investment expert and strategy professor at the Rice University school of business.

“We have never seen something like this happen,” Professor Zhang told The Independent. “By partnering with those state-owned companies in Russia, they know they’re going to keep generating oil and gas and it may be perceived as helping the Russian government fund the war in Ukraine. The damage to their images is something they cannot bear to take.”

It’s a sign that calls from activists and investors for companies to swiftly incorporate environmental, social, and corporate governance (ESG) frameworks into their operations are actually working, according to Jonathan Elkind, a former Assistant Secretary for International Affairs at the Department of Energy and senior research scholar at Columbia University’s Center on Global Energy Policy. ESG business strategies incorporate not only standard business considerations like profits and losses into decision-making and investment, but also environmental, social, and political impacts. It’s becoming an increasingly potent movement on Wall Street and beyond, where activist investors scored a shock victory last summer and scored three seats on ExxonMobil’s board of directors.

“If companies are getting constant pressure to attach greater importance to ESG performance, if they then took the attitude that Russia’s actions didn’t matter, they’d be in for a world of very difficult questions to respond to,” he said.

Still, despite the major financial blow to the Kremlin, ditching Russian oil might actually make the climate crisis worse, given the methods Exxon and others plan to use to tackle emissions, and national governments’ sputtering attempts to make climate policy.

Thus far, Exxon hasn’t offered a timeline of when it will actually leave Russia, a process that could drag on as it seeks to safely sell and hand over operation of complex projects like Sakhalin.

“Before we can exit, we first have to safely discontinue operations, then address the contractual and commercial obligations of the venture. These steps are underway,” an Exxon spokesperson told The Independent, though the company declined to offer specifics on that timeline, or whether lost profits in Russia might impact its climate goals.

Other firms that are leaving Russia, like BP and Shell, have explicitly said that fossil fuel profits are what help fund their climate goals.

And those are companies considered to be more committed to tackling climate change than Exxon, which announced early this year it had an “ambition” to be net zero by 2050.

Activists have been highly critical of Exxon’s net zero strategy. It involves plans to invest at least $15bn in things like carbon capture, biofuels, electrification of operations, and hydrogen energy. However it fails to account for Scope 3 Emissions – greenhouse gas releases from customers using its products – even as other firms like Shell and Norway’s Equinor plan to address this activity, which makes up the vast majority of emissions from fossil fuel use.

What’s more, global demand from oil isn’t going anywhere, so private equity firms, who won’t face the same kind of scrutiny as public companies, may sweep into Russia to buy up oil assets, while big drillers may look to dirtier oil fields to meet the demand for energy, all while reaping the windfall that sky high oil prices have brought them in recent weeks.

Many governments, meanwhile, even those which have made big-picture commitments to slashing emissions, are also facing immense domestic pressure over rising gas prices and securing non-Russian oil supplies. The European Union has said it intends to boost renewables production and cut Russian oil imports by two-thirds this year, and the UK wants to phase out Russian oil entirely. But both regions’ oil will still need to come from somewhere.

“We’re seeing a spike in oil prices, and that oil companies will be successful in exploiting this scramble from Russian oil and gas by convincing governments to make investment decisions that lock even greater levels of fossil fuel dependency,” said Erica Westenberg, governance programmes director at the Natural Resource Governance Institute, a think tank.

“There are multiple narratives that are kind of at play. The reality is likely that both of those narratives could play out, in parallel or maybe at different timelines. It’s hard to say which one will carry the day.”

In the US, which only imports about 7 per cent of its oil from Russia, leaders have taken this moment both to ban Russian oil imports, as the Biden administration did in early March, while at the same time pressing for more investment and international trading in fossil fuels.

The White House has reportedly been considering new oil deals with Iran, Venezuela, and Saudi Arabia to increase the fuel supply. Oil industry groups and their Republican allies quickly began pressing President Biden to restart the Keystone XL pipeline, even though the export-focused pipeline bears largely secondary importance to the US energy supply.

“All we need to do is have this administration come out and clearly state that we’re going to reopen the Keystone XL pipeline, that we’re going to get back in the energy business,” Tennessee Senator Bill Hagerty said this month, arguing it would cut down on gas prices even though experts say this isn’t true.

Even before Russian troops began invading Ukraine, the American Petroleum Institute, a major fossil fuel industry lobbying group, was pushing for more drilling.

“As crisis looms in Ukraine, US energy leadership is more important than ever,” the group, wrote on Twitter in late February. “Let’s unleash American energy. Protect our energy security.”

Progressive Democrats who have championed climate action, like Senator Ed Markey of Massachusetts and Representative Ro Khanna of California, propose replacing banned Russian oil imports with clean energy over time via the Severing Putin’s Immense Gains from Oil Transfers (SPIGOT) Act, though the legislation is unlikely to move forward in a 50-50 Senate that won’t even pass the president’s clean energy priorities.

In Europe, meanwhile, countries like Germany have halted the $11bn Nord Stream 2 gas pipeline linking Europe and Russia, and the EU has said it hopes to tax oil companies on their current windfall profits from the increased oil price.

That said, Germany is also considering ramping up coal production, trading, and power generation to replace its dependence on Russian gas. That effort, according to German vice-chancellor and Green Party member Robert Habeck, will rely on a form of coal known as lignite, or “brown coal,” one of the dirtiest forms of coal in terms of carbon emissions and polluting particulate matter.

“Brown coal is usually the first thing you want to run the opposite direction of,” said Mr Elkind, the Columbia energy scholar. “The fact that this prominent leader in the German Green Party called for an increase in lignite should tell you a lot about the seriousness of the situation that Germany thinks it is facing. That’s all bad for the climate.”

Taken together, the world stands at an energy crossroads. If Russia maintains its current aggression in Ukraine, large parts of North America and Europe may cease to rely on its oil and gas production for the long term.

“I hope that this represents a wake-up call for the industry and for investors in the industry to really have a moment of reckoning around the types of reputational and governance risks that doing business with corrupt and kleptocratic regimes can create, and how susceptible countries can become to energy dependency when it comes to fossil fuel reliance,” said Ms Westenberg, of Natural Resource Governance Institute.

What comes in to replace that Russian supply is a live question. The world, and Europe especially, has become accustomed to this oil supply, despite the cruelty of the regime that produces it.

Some argue that now is the moment to cut ties with Russian violence against its neighbours, and the violence that fossil fuels will bring to the world if we don’t break our reliance upon them.

“Fossil fuels have helped build a cruel, violent, and unequal world,” Kate Aronoff argued in The New Republic. “Decarbonization might be a chance to create a better one.”

UN Secretary General Antonio Guterres has said increasing fossil fuel use amid the war in Ukraine is akin to “madness” and “mutually assured destruction,” just as using nuclear weapons was during the Cold War.

However, it seems the only way more renewables would come online to replace Russian oil is if governments and investors alike had the same kind of urgency around climate change as they did on the invasion of Ukraine.

Exxon CEO Darren Woods has said that his decision was partly motivated by the fact that sweeping international sanctions on Russia had made it impossible to stay atop a project like Sakhalin and legally do business. No such campaign of global climate sanctions has been implemented against big emitters.

There’s only so much an individual investor or fossil fuel company can do, says Columbia’s Jonathan Elkind. Instead, it is those same governments leading the international campaign against Russian and Vladimir Putin who must step up and lead the same kind of global effort against the climate crisis.

“People are and should be horrified by the devastation that has unfolded in Ukraine. People aren’t sufficiently but should be horrified by the loss of lives that is already happening today as a consequence of a changing climate,” he said.

“Personally, I am more inclined to direct blame at governments that are failing to institute policies that signal very unmistakably to the general public and to companies and investors what are the harms that are associated with continued emissions of greenhouse gas. That’s the job of government, to step up to the plate.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks