Rising temperatures and melting ice could bring alien species to Antarctica, study warns

Floating rubbish from Africa, Australia and South America could bring diseases and invasive species

Antarctica’s ecosystems may soon face a new threat: alien species carried by floating rubbish from Australia, Africa and South America.

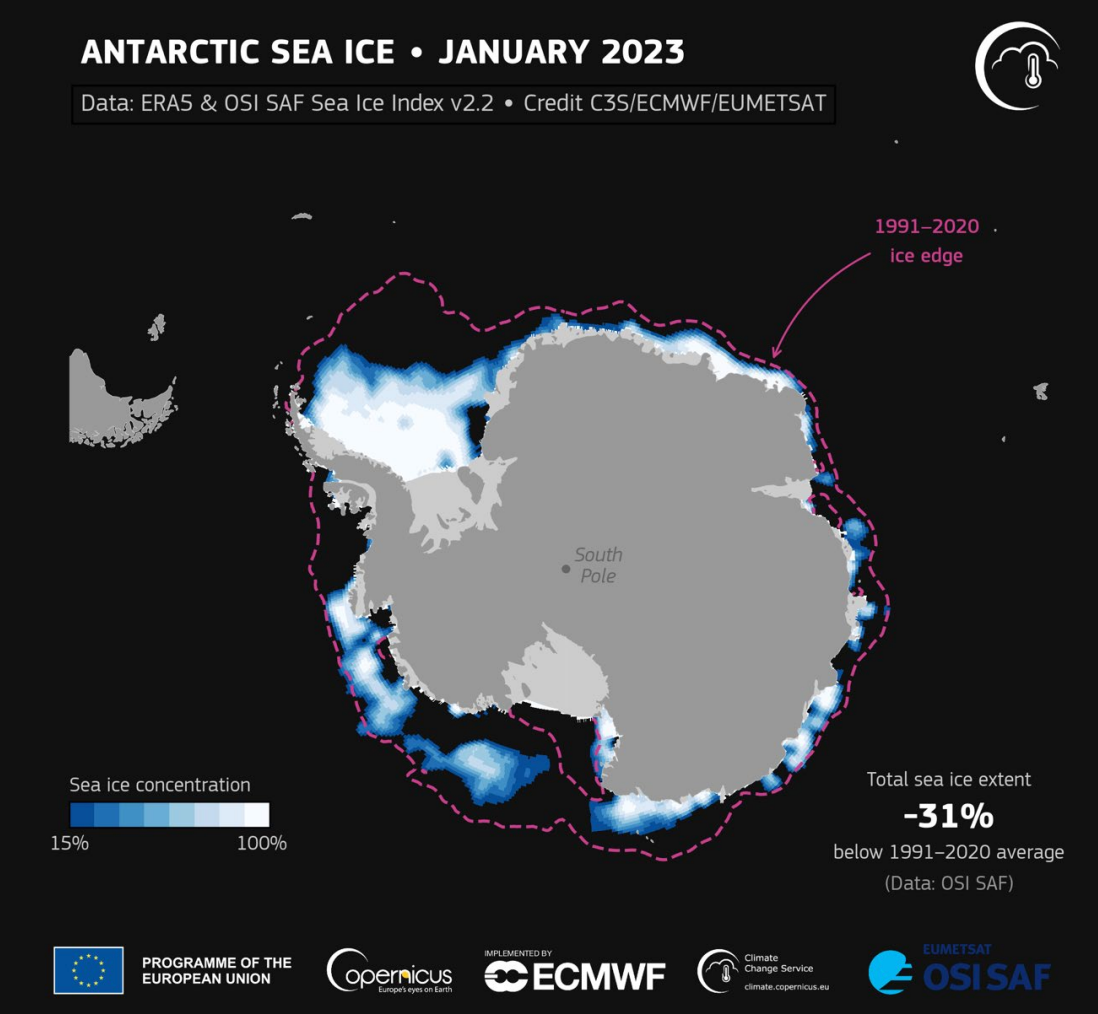

As the planet warms and sea ice melts, non-native species could invade the Antarctic coastline, disrupting its fragile marine life, according to a new study published in Global Change Biology.

For years, scientists believed that only remote islands in the Southern Ocean posed a risk of introducing new species to Antarctica. But the new study, conducted by a team of researchers from UNSW Sydney, ANU, the University of Otago, and the University of South Florida, shows that floating objects like kelp, driftwood and even plastic can reach the icy continent from farther away.

The study’s lead author, Dr Hannah Dawson, explained that increasing rubbish in the oceans provides more opportunities for these species to hitch a ride to Antarctica.

"We knew that kelp could raft to Antarctica from sub-Antarctic islands, but our study suggests that floating objects can reach Antarctica from much further north, including South America, New Zealand, Australia, and South Africa," Dr Dawson said.

This journey across the Southern Ocean isn’t theoretical. The researchers used advanced computer models to simulate ocean currents and track the movement of floating debris from various southern landmasses over a period of 19 years. The results showed that debris could reach the Antarctic coastline every year, with some items arriving in as little as nine months.

The concern is that as temperatures rise and sea ice diminishes, these non-native species might find it easier to survive and establish themselves in Antarctica.

"Sea ice is very abrasive and acts as a barrier for many non-native species," Dr.Dawson explained.

"But with the recent decline in Antarctic sea ice, living things floating at the surface or attached to debris could have an easier time colonising the continent."

According to the researchers, one particular worry is the impact of large seaweeds like southern bull kelp and giant kelp.

“Southern bull kelp and giant kelp are very big, often more than 10m long, and create forest-like habitat for a lot of small animals, which they can carry with them on the long rafting trips to Antarctica,” said professor Crid Fraser from the University of Otago.

“If they colonise Antarctica, marine ecosystems there could change dramatically.”

Most of the floating debris and potential invasive species are likely to land at the tip of the Antarctic Peninsula, the study found.

This region has relatively warm ocean temperatures and is often free of sea ice, making it the most vulnerable spot for non-native species to settle.

“These factors make it a likely area for non-native species to first establish, which may have big impacts on ecosystems,” the study said.

With Antarctica’s natural defences weakening, the arrival of foreign species could change its ecosystems in ways scientists are yet to fully understand.

Scientists are calling for increased vigilance and research to prevent these potential invaders from turning one of Earth’s last pristine environments into a battleground for survival.

Antarctic sea ice has been shrinking in recent years, hitting near-record lows in 2024. In February this year, the ice covered just 768,000 square miles, which is 30 per cent less than the average from 1981 to 2010.

This was the second-lowest amount of ice ever recorded by satellites since 1979 and the third year in a row that the ice had dropped below 2 million square miles.

Researchers at the the British Antarctic Survey who analysed the low levels of sea ice around Antarctica in 2023 said the decline was a one-in-2,000-year event without the climate crisis but four times more likely because of its effects.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks