Farmers could forgo harmful fertilisers by growing black-eyed peas, scientists say

The idea was propogated by a black scientist in the early 20th century

Growing black-eyed peas could eradicate the need for expensive and environmentally-damaging fertilisers for gardening, research from a US university has confirmed.

Legumes such as black-eyed peas, also known as cowpeas, are a unique category of crops in that they attract “substantial amounts” of nitrogen that is essential for also growing other plants.

They do this by forming a symbiotic relationship with nitrogen-fixing soil bacteria called rhizobia.

Rhizobia is attracted to the plant through chemicals the legumes crop emits through the roots. Then the roots form tumour-like nodules that protect the bacteria and supply them with carbon, for which the plant receives nitrogen to turn into ammonia.

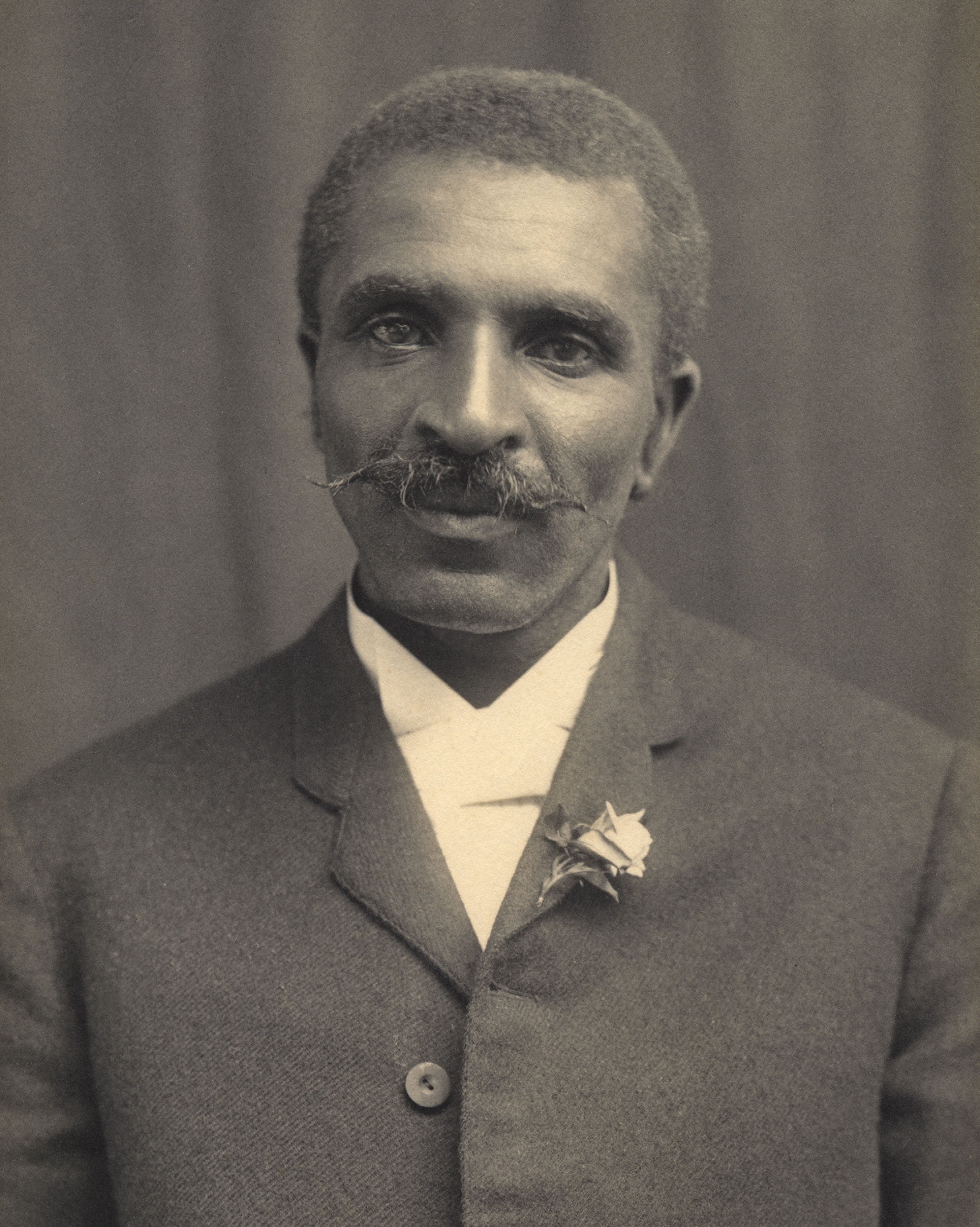

The most prominent black scientist of the early 20th century – agriculturalist and inventor George Washington Carver – had popularised, researched, and taught on the growing of black-eyed peas, peanuts, soybeans, and sweet potatoes to improve soil conditions.

Now, scientists led by plant pathologist Gabriel Ortiz, of University of California Riverside (UCR), have said that modern-day farmers could forgo the use of costly and environmentally-damaging fertilisers by planting legumes.

Dr Ortiz said: “When the plant senses it is going to die, it releases the bacteria into the soil, replenishing it.

“Growers could alternate seasons of legumes with other crops, leaving the soil full of nitrogen-fixing bacteria that reduce the need for fertiliser.”

A black-eyed peas plant’s ability to attract the beneficial bacteria isn’t diminished by modern farming practices, the UCR research shows.

Joel Sachs, UCR professor of evolution and ecology, said: “In fact, some of the strains in the experiment appear to have gained more benefit from bacteria than their wild ancestors.”

He added: “To make agriculture more sustainable, one of the things we need to do is focus on the plant’s ability to get services from microbes already in the soil, rather than trying to get those services by dumping chemicals.”

When already-madenitrogen fertiliser is applied to plants at a rate faster than it can be used, the excess can end up in the atmosphere as a greenhouse gas or washed out into lakes, rivers and seas.

In the aquatic system, nitrogen feeds “harmful algal blooms” – rapid accumulations of algae that typically turn the water green – that use up all the oxygen and end up killing fish.

The UCR experiments involved 20 different types of black-eyed peas, and “point toward a genetic basis for their symbiotic abilities” – the researchers said.

The research results have been published in the biology journal Evolution.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks