Millipedes ‘as big as cars’ once roamed Northern England, rare fossil discovery reveals

Evidence of largest invertebrates of all time found in Northumberland

Just days after the discovery of an extant millipede species with over a thousand legs in Australia, the world of diplopodology – the study of millipedes – is being rocked by a fossil find which has revealed the biggest millipede ever to have lived.

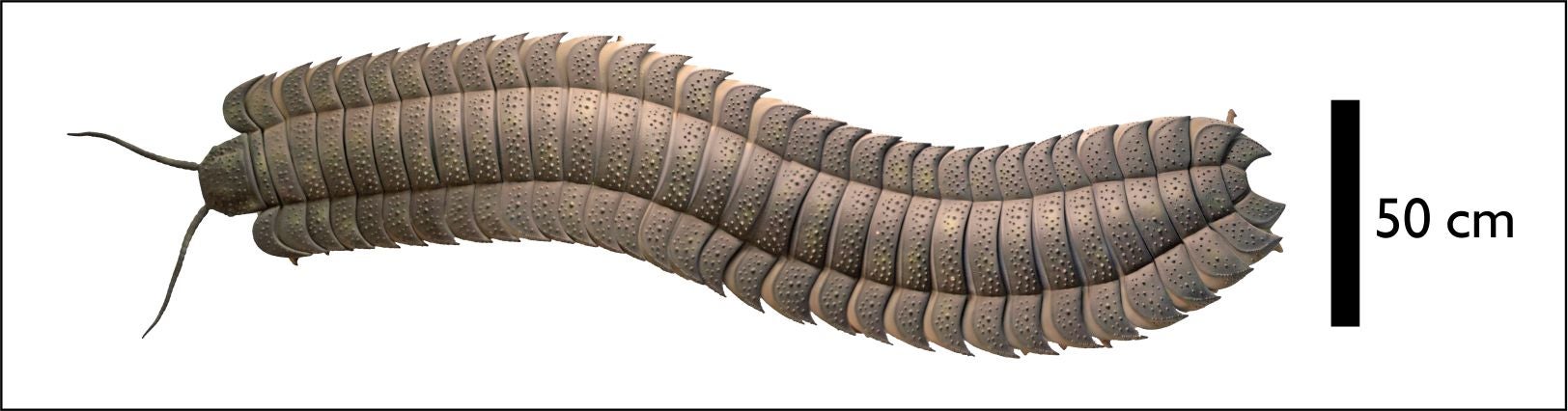

The species, which scientists at the University of Cambridge said was “as big as a car”, apparently roamed what is now Northern England during the Carboniferous period – around 100 million years before the age of the dinosaurs.

Back then, the land which became the cold, damp country we now know as Great Britain lay much closer to the equator, so Northumberland – where the fossil was found – would have had a more tropical climate.

The fossil reveals the creature, called Arthropleura, was the largest-known invertebrate animal of all time – even larger than the ancient sea scorpions that were the previous record holders.

The specimen was discovered in January 2018 in a large block of sandstone which had fallen from a cliff onto the beach at Howick Bay in Northumberland.

“It was a complete fluke of a discovery,” said Dr Neil Davies from Cambridge’s Department of Earth Sciences, the paper’s lead author. “The way the boulder had fallen, it had cracked open and perfectly exposed the fossil, which one of our former PhD students happened to spot when walking by.”

The research team said invertebrates such as this species and early amphibians lived off the scattered vegetation around a series of creeks and rivers. The specimen identified by the researchers was found in a fossilised river channel, and they said it was likely a moulted segment of the Arthropleura’s exoskeleton that filled with sand, preserving it for hundreds of millions of years.

The fossil was extracted in May 2018 with permission from Natural England and the landowners, the Howick Estate. “It was an incredibly exciting find, but the fossil is so large it took four of us to carry it up the cliff face,” said Dr Davies.

The fossil was brought back to Cambridge so that it could be examined in detail. It was compared with all previous records and revealed new information about the animal’s habitat and evolution.

The researchers said it likely only existed in places that were once located near the Equator.

Previous reconstructions have suggested that the animal lived in coal swamps, but this specimen showed Arthropleura preferred open woodland habitats near the coast.

There are only two other known Arthropleura fossils, both from Germany, and both much smaller than the new specimen.

Although this is the largest Arthropleura fossil skeleton ever found, there is still much to learn about them, the team said.

“Finding these giant millipede fossils is rare, because once they died, their bodies tend to disarticulate, so it’s likely that the fossil is a moulted carapace that the animal shed as it grew,” said Dr Davies.

“We have not yet found a fossilised head, so it’s difficult to know everything about them.”

The great size of Arthropleura has previously been attributed to a peak in atmospheric oxygen during the late Carboniferous and Permian periods, but because the new fossil comes from rocks deposited before this peak, it shows that oxygen cannot be the only explanation.

The researchers believe that to get to such a large size, Arthropleura must have had a high-nutrient diet.

“While we can’t know for sure what they ate, there were plenty of nutritious nuts and seeds available in the leaf litter at the time, and they may even have been predators that fed off other invertebrates and even small vertebrates such as amphibians,” said Dr Davies.

Arthropleura animals crawled around Earth’s equatorial region for around 45 million years, before going extinct during the Permian period. The cause of their extinction is uncertain, but could be due to global warming that made the climate too dry for them to survive, or to the rise of reptiles, who out-competed them for food and soon dominated the same habitats.

The fossil will go on public display at Cambridge’s Sedgwick Museum in the New Year.

The research is published in the Journal of the Geological Society.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks