IoS Charity Appeal: The DNA trap to catch ivory poachers

An Edinburgh geneticist uses forensics to track animals killed in the world’s fourth biggest illegal trade – and their killers

You just have to take one glance inside Dr Rob Ogden’s freezer to know it is no ordinary one. DNA samples from a rhino, a Vietnamese tiger, a golden eagle, an antelope and a wild cat are all stored inside.

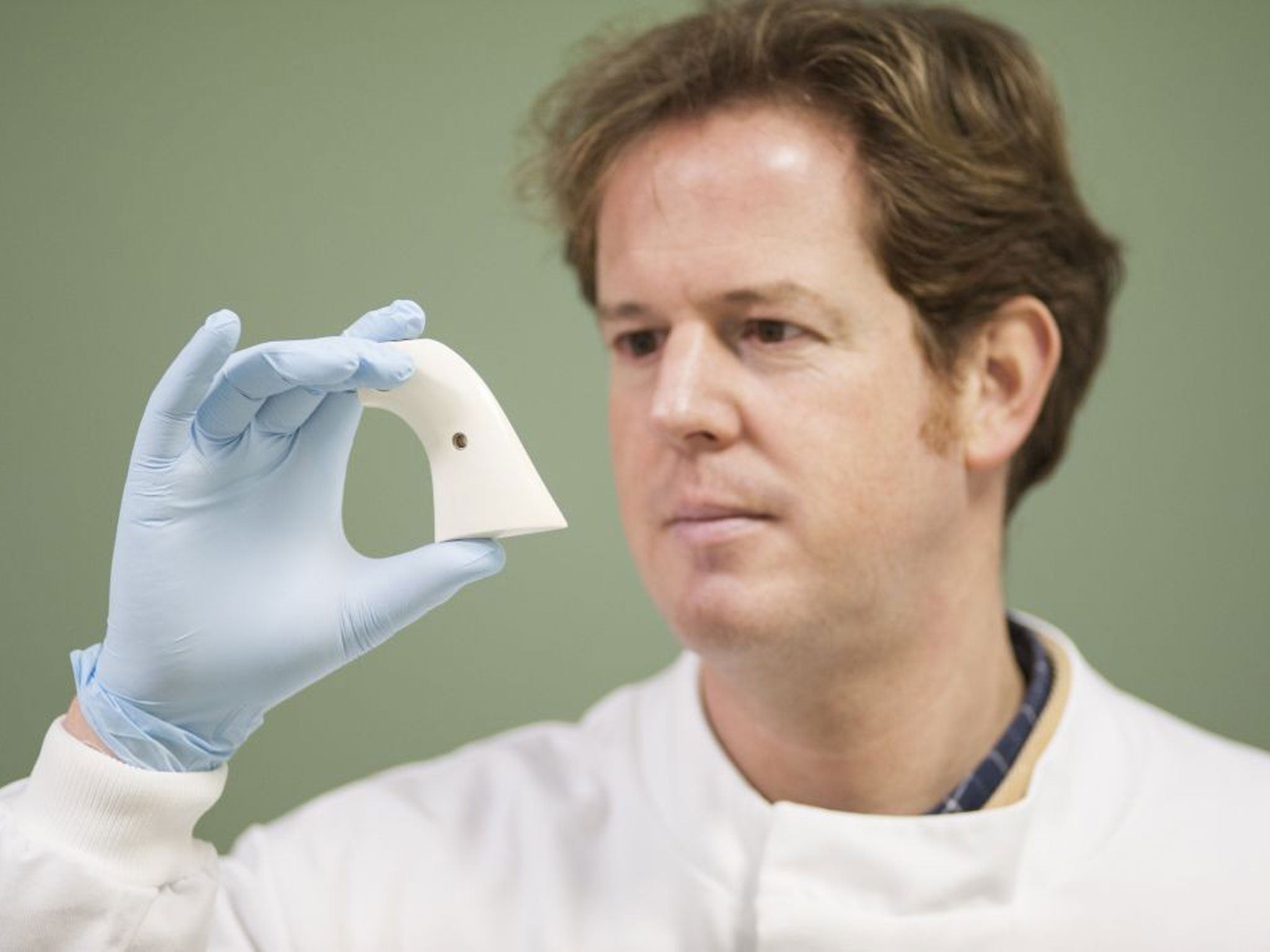

Then there is the block of ivory on his shelf, the size of a door stop, which belonged to an African elephant long before it was brought to his two-room laboratory located at the back of Edinburgh zoo.

The 38-year-old geneticist might not look like someone associated with fighting global wildlife crime – now estimated to be worth tens of billions of dollars each year and ranked as the fourth biggest illegal trade after narcotics, human trafficking and counterfeiting – but among those in the know, he is recognised as a pioneer.

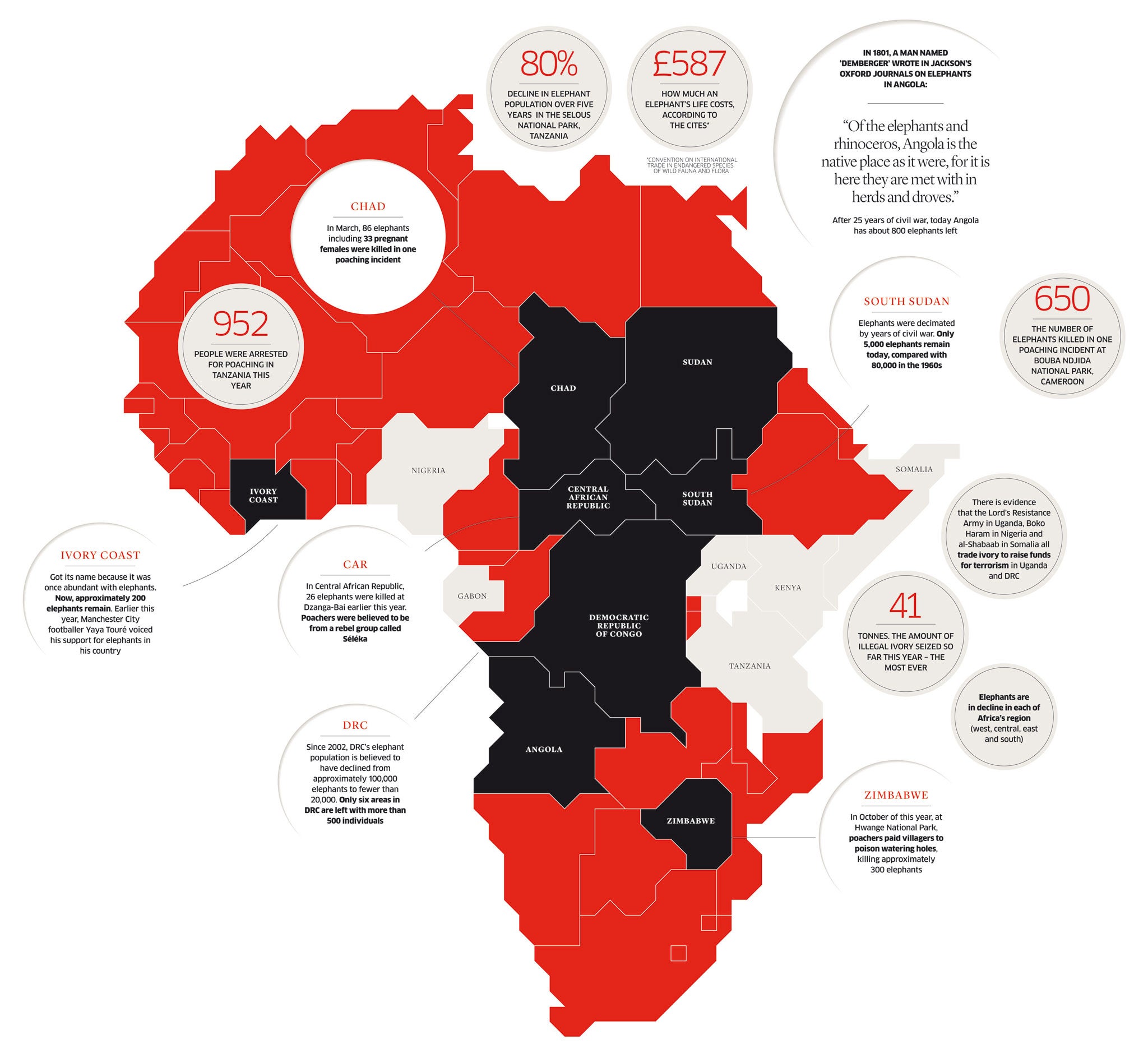

The illegal ivory trade activity worldwide has more than doubled since 2007, and estimates suggest that about 100 African elephants a day are being killed for their ivory.

According to the International Union for Conservation of Nature, 2011 had the highest levels of poaching in 16 years. About 22,000 were illegally killed last year, and it has been warned that 20 per cent of Africa’s elephants could be killed in the next decade if poaching continues at the current rate.

We know about military-style enforcement on the ground. Rangers are equipped with night-vision goggles and guns. Poachers opt for AK-47s or machetes.

But far away from the killing fields, Dr Ogden is busy as the programme director for Trace Wildlife Forensic Network, promoting forensic science as a way of conserving biodiversity and investigating the growing crime. For years, and almost in isolation, he worked with law enforcement agents in this country, using DNA forensics to link an item – a piece of elephant ivory, for example – back to its species. In the case of elephants, African or Asian.

Thanks to genetic mapping, this DNA can then be traced to a region, enabling enforcers to understand where killings are taking place. Experts can even analyse levels of radioactive carbon, known as carbon-14, to determine when animals lived or died. This is useful in court, because according to the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (Cites), only animal products that have been moved across international borders after 1947 are banned. But now, after having trained the scientist at the only dedicated wildlife DNA forensics unit in the country (also based near Edinburgh), he is focused on training scientists across South-east Asia to use forensic techniques. This also happens to be the area where demand for illegal African ivory is rocketing.

“Ultimately, I’m using tools I’ve got at my disposal to minimise the loss of biodiversity,” Dr Ogden says. “In an ideal world, we wouldn’t need to do what we’re doing; we would all be out of business. But there’s been a surge in the illegal wildlife trade, and to address it we need enforcement techniques, a reduction in demand, poverty alleviations, and people to take charge of their own natural resources. We are helping them in doing that.”

So far, Dr Ogden and his colleague, Dr Ross McEwing, have trained people in at least 20 countries across the world. They developed a special DNA forensics lab in Malaysia, in Vietnam and in Bangkok – as well as training people to work in them. In Thailand, the government has spent almost $1m on a lab that the duo built up; in the first 12 months it processed 26 cases. In Malaysia, criminal investigations involving forensic DNA analysis has increased 80 per cent each year since the lab opened. They are apparently “swamped”; there about 2,300 ivory items waiting to be examined.

Dr Ogden is developing a project with the government of Gabon on Africa’s west coast. In the past decade, 11,000 forest elephants were killed in one of the country’s parks alone, shocking people there and abroad.

He will potentially work with officials to map the DNA of elephants in different regions, so that it is possible to trace newly slaughtered animals back to the part of the country from which they came.

The process is not easy. First you have to deconstruct a piece of ivory until you can get a sample. DNA extraction can take several days. Then scientists take a small section of the genome and make millions of copies. The final part of the process is the DNA sequencing (to identify the species) or DNA profiling (to identify individuals).

And it’s not cheap. Dr Ogden says that it costs £250,000 a year to carry out his capacity-building and to run his lab in Edinburgh, which is partly funded by the Royal Zoological Society of Scotland. He also undertakes conservation work for the society on the premises.

But it seems the work is catching on. His protégée, Dr Lucy Webster, a senior molecular biologist at Science & Advice for Scottish Agriculture (Sasa), is now believed to be the only scientist dedicated to wildlife DNA forensics in Britain. She has worked on at least 100 cases since she was trained by Dr Ogden in 2011, most of which have been criminal. While most cases in Britain involve deer poaching, hare coursing and badger baiting, Dr Webster worked on an ivory case earlier this year which centred on species identification. The case ended up in court, but only because it was not known if the owner had the right documentation to sell the antique tusk.

Dr Webster, who is also setting up a rhino DNA database to track horns kept in museums across the UK, said she saw forensics as an “incredibly applied way to benefit wild animal conservation and to prevent cruel treatment” today.

As for Dr Ogden, he is in the process of developing a database across Southeast Asia for tigers held in captivity. The aim is that it will enable people to identify newly captured tigers back to their source or even back to the individual. It will also be able to prove if a tiger cub has been born to a captured animal or whether it has been removed from its family in the wild. He is also working on a method of tracing the geographical origin of fish stocks in European waters, but particularly around the UK, and determining if any illegal fishing has taken place.

But Dr Ogden still believes the use of forensics in wildlife crime is rare. “Perhaps only 10 people work full time in wildlife DNA forensics worldwide,” he said. Unfortunately, it looks as if this number is set to grow.

The price of poaching

1800 An estimated 26 million elephants roam the African continent as the first Europeans begin building forts on Africa’s uninhabited islands.

1910 At the turn of the century, European empires stretch across Africa. Ivory is in vogue in Europe and America. Africa’s elephant population halves to about 10 million.

1979 Elephant populations dwindle to 1.3 million because of growing demand from the West.

1980s By 1989, there are believed to be only 600,000 elephants remaining in Africa. Kenya’s population drops from 167,000 to 19,000.

1989 Cites bans the international trade in ivory; the ban comes into force in 1990. Kenya destroys its entire ivory stockpile in a gesture against the ivory trade.

1990s After the ban, Tanzania’s elephant population increases from 55,000 to over 125,000. The Kenyan population also grows to more than 30,000 by 2007 from the historic low of 16,000.

1999 Under mounting pressure from African leaders, Cites allow a “one-off” sale of stockpiled ivory. Japan buys 55 tons of ivory from Zimbabwe, Namibia and Zimbabwe for £3m.

2008 Cites grants China permission to import elephant ivory from government stockpiles; 102 tons of stockpiled ivory is sold, half of it going to Japan, and half going to China for £9.3m.

2009 There is a huge spike in the number of large ivory seizures, with 14 seizures totalling 23,235 tons.

2011 Officials from Cites document that between 25,000 and 50,000 of Africa’s elephants are believed to have been killed illegally since records began.

2013 Approximately 450,000 elephants remain in Africa. There are 18 large-scale seizures of illegal ivory.

Jack Hall

How you can help

Your donation to Space for Giants can help save these magnificent creatures from extinction.

£30 can support a wildlife ranger for a week to protect elephants in northern Kenya.

£50 will provide a pack that could save the life of a wildlife ranger injured protecting elephants.

£75 will support the training of a law enforcement officer on criminal justice processes, increasing the chances of successful prosecutions and higher fines for wildlife crime.

£100 could secure for ever one acre of a 60,000-acre elephant sanctuary in northern Kenya.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks