Vegetarian elephant bird weighing almost a tonne named world’s largest

Vorombe titan roamed Madagascar until 1,000 years ago, but it is not clear what caused the species to be wiped out

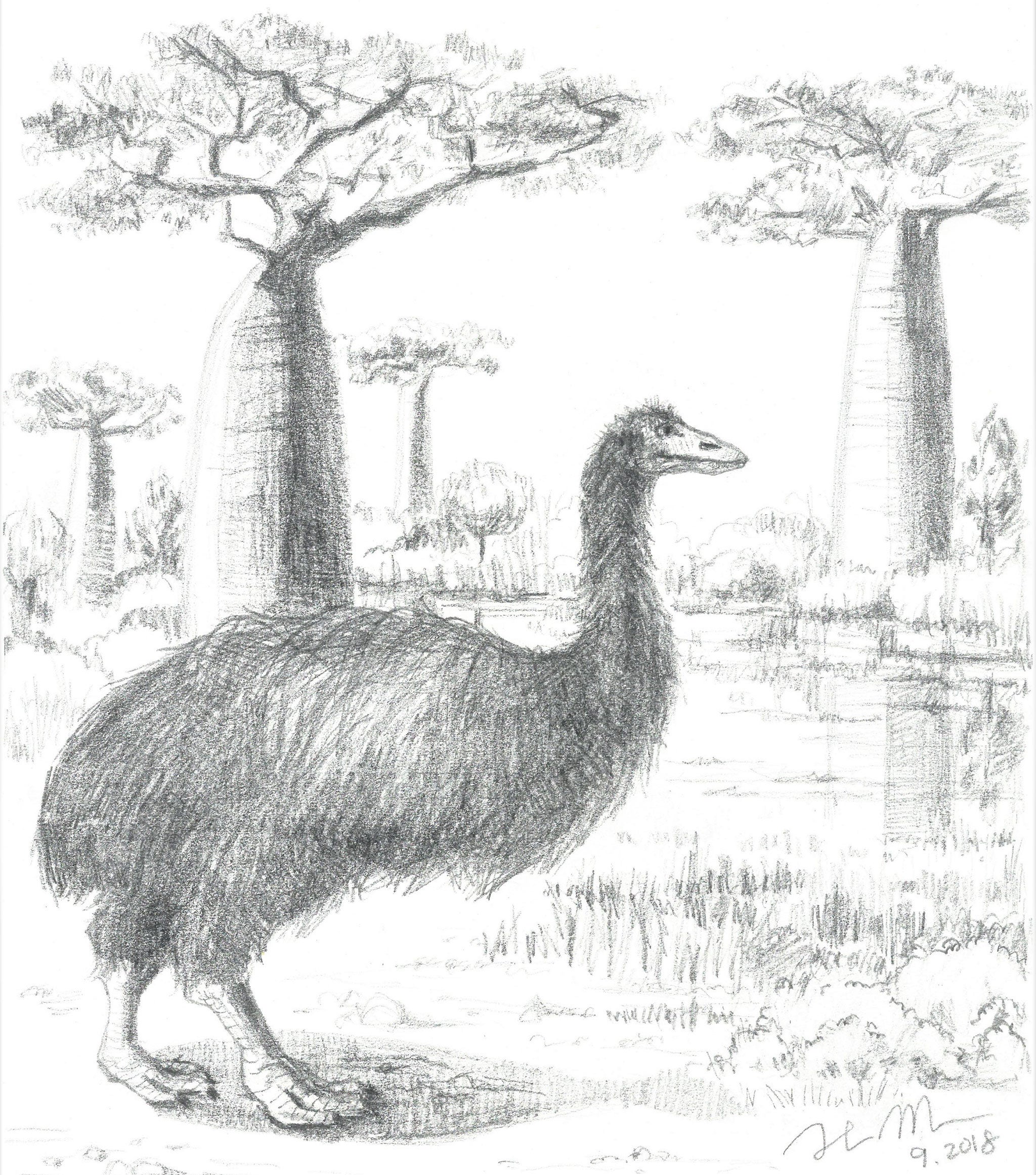

A three-metre-tall ostrich-like creature that weighed almost a tonne has been awarded the title of the world’s largest bird.

Vorombe titan, which literally means “big bird” in Malagasy and Greek, is an extinct flightless bird which was once widespread on Madagascar. It survived on a plant based diet.

By studying hundreds of elephant bird bones from museums around the world, researchers at the Zoological Society of London (ZSL) have now provided a definitive answer to decades of conflicting evidence over which winged creature was truly the world’s largest.

They found that V titan was a distinct species of the feathered elephant bird weighing up to 860 kg.

In 1894, British scientist CW Andrews came across a specimen which was given the name Aepyornis titan.

For years afterwards it was dismissed as simply an unusually large specimen of another species, Aepyornis maximus, which until now considered to be the world’s largest bird.

However, ZSL’s research revealed that Andrew’s "titan" bird was in fact, a distinct species.

The shape and size of its bones were found to be so different from all other elephant birds that it has now been given the new genus name, Vorombe.

Its new classification makes it the world’s largest bird with a body mass to rival some dinosaur species including the herbivorous europasaurus and europasaurus.

Despite their powerful legs and fearsome talons the V titan birds were peaceful herbivores, living mainly on fruit.

One of their giant eggs could have fed an entire family, although there is no evidence of direct nest raiding.

“Elephant birds were the biggest of Madagascar’s megafauna and arguably one of the most important in the islands evolutionary history – even more so than lemurs," said Dr James Hansford of the ZSL's Institute of Zoology and lead author of the study published in the Royal Society journal, Open Science.

“This is because large-bodied animals have an enormous impact on the wider ecosystem they live in via controlling vegetation through eating plants, spreading biomass and dispersing seeds through defecation. Madagascar is still suffering the effects of the extinction of these birds today.”

V titan is thought to have roamed Madagascar until 1,000 years ago, but it is not clear what caused the species to be wiped out.

A previous study by a team of ZSL scientists discovered that ancient bones from the extinct Madagascan elephant birds showed cut marks and fractures consistent with hunting and butchery by prehistoric humans.

Using radiocarbon dating techniques, the team were then able to determine when these giant birds had been killed, which led them to reassess when humans first reached Madagascar.

Previous research on lemur bones and archaeological artefacts had suggested that humans first arrived in Madagascar 2,400-4,000 years ago.

However, the new techniques provided evidence of human presence on Madagascar as far back as 10,500 years ago – making these modified elephant bird bones the earliest known evidence of humans on the island.

Professor Samuel Turvey, co-author on the latest study, said: “Without an accurate understanding of past species diversity, we can’t properly understand evolution or ecology in unique island systems such as Madagascar or reconstruct exactly what’s been lost since human arrival on these islands.

“Knowing the history of biodiversity loss is essential to determine how to conserve today’s threatened species.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks