Endangered pangolins threatened as coronavirus hits conservation funds

We are working with conservation charity Space for Giants to protect wildlife at risk from poachers due to the conservation funding crisis caused by Covid-19. Help is desperately needed to support wildlife rangers, local communities and law enforcement personnel to prevent wildlife crime. Donate to help Stop the Illegal Wildlife Trade here

The conversation takes place over WhatsApp, lasting a few days. Professor Ray Jansen convinces his contact that he is a legitimate buyer and a meeting is arranged. The middleman meets Jansen first and signals to his partners to bring in the package.

Then the South African police move in, arresting the hunters, the middleman, and seizing the package: a live, and very stressed, pangolin.

“The African trade in pangolins has grown exponentially in recent years,” explains Professor Jansen, who is head of the African Pangolin Working Group (APWG). “The word is out that pangolins are worth huge money.”

Two words have made it into our vernacular since February: the first is furlough and the second is pangolin. The scaled mammal has achieved notoriety for being the most trafficked animal in the world, as well as potentially having a role in the outbreak of Covid-19.

But what is a pangolin and why is it under threat? This is the first in a two-part series explaining the current state of these scaled mammals across the world, as well as the sophisticated networks that take them from forested burrows to markets on the other side of the world.

“One of the biggest challenges we have is that we know relatively little about pangolin distribution and behaviour,” admits Claire Okell, the director of the Kenya-based Pangolin Project. “Their population numbers are unknown. The challenges that face us learning about pangolin include that they are predominantly nocturnal, solitary creatures that and mostly live in burrows during the day and are very shy.”

Brent Stirton, a wildlife and conservation photographer who published a photo series on pangolin poaching in 2010, tells me that they are “one of those species that are disappearing so quickly that we might never know much about them”.

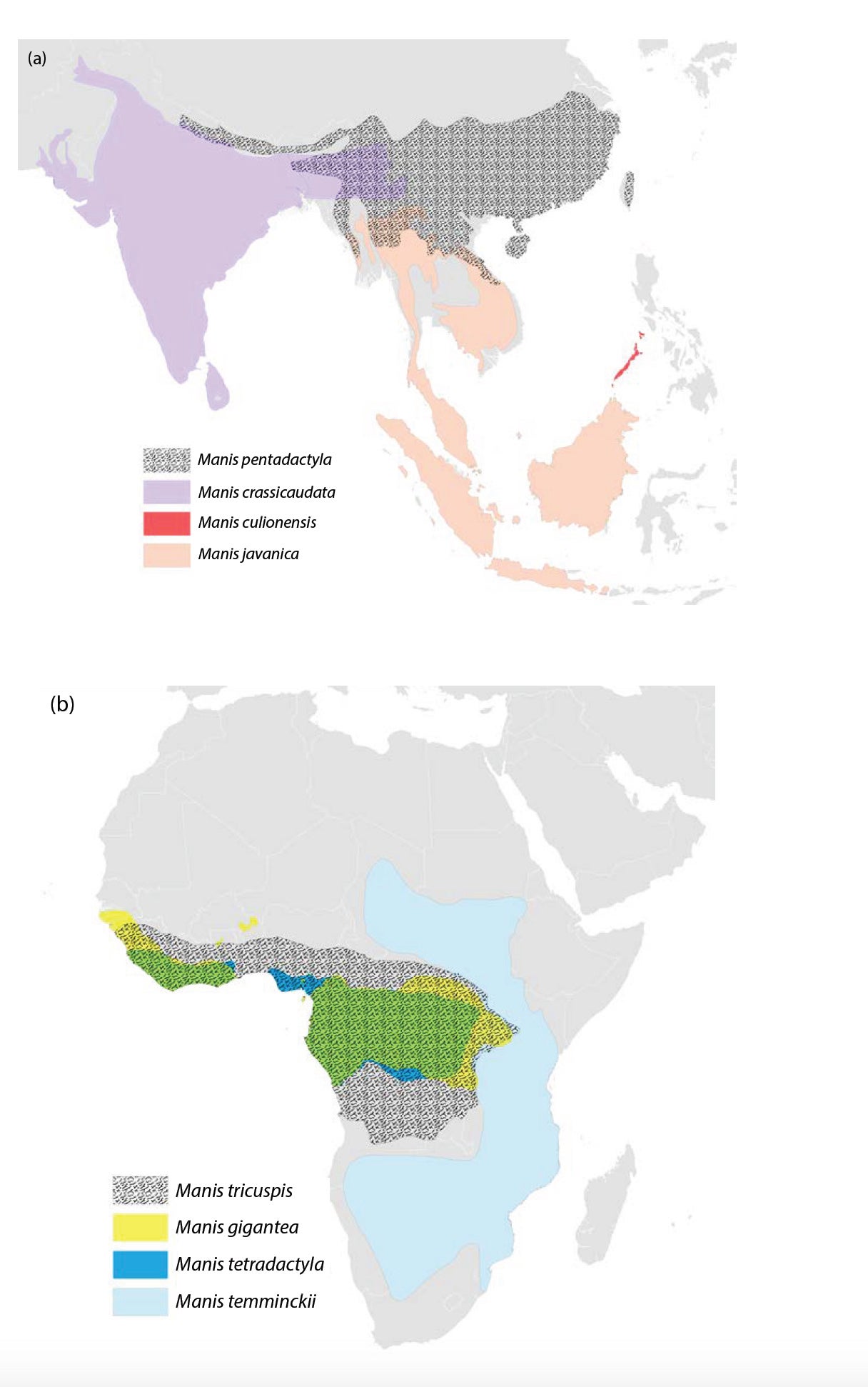

Here is what we do know: pangolins are the only wholly-scaled mammal. Native to parts of Africa and South-East Asia, they are distinct for their keratin scales and long sticky tongues – designed to suck up ants and termites.

They have the longest tongue-to-body ratio of any mammal. Their long claws dig out anthills and their tongue drags insects past its toothless mouth straight into the stomach.

The word ‘pangolin’ comes from the Malay ‘peng-guling’ meaning ‘roller’, because these animals’ defence mechanism is to roll up into an armoured ball with their thick tail as defence.

They are silent and solitary mammals that often live in the burrows of other animals like aardvarks. All eight species of pangolin, the four native to Africa and the four native to Asia, are list on Appendix I of Convention for the International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES), meaning they are endangered.

“We believe pangolins are a key part of a healthy soil and ecological system,” adds Dr Okell. “They consume ants and termites and will be playing a role in returning biomass to the soils and, in turn, supporting vegetation diversity.” They also only inhabit specific burrows for a short period of time before leaving them. These are then used by multiple other mammal species.

Pangolins have a long history of interaction with humans and many cultures in Africa have deep-seated respect for the animals but traditional knowledge and stories about pangolin (and other species) are slowly being lost.

“The Masai [a semi-nomadic people of Kenya] have a specific word for pangolin: “Entaboi” that connotes bad luck,” explains Dr Okell. "However, elders report that traditionally the meaning was protective: the use of the word, originally meant that people should respect the pangolin and if you do not "bad luck will come to you".

Maasai elders regarded pangolin as something special and to be blessed when seen, they report that “if you see a pangolin, you have to cut down branches from a sacred tree to lay around it, and bless it with milk”.

A large part of the Pangolin Project’s mission is providing awareness about pangolins.

Nowadays farmers may kill pangolins for fear that they will damage their crops, others use them for traditional and spiritual medicine. The NGO works to educate rural Kenyans about how to protect the species. It also works with rangers, police and judicial systems.

However, the international trade in pangolins is now the predominant threat and the poaching of pangolins for the international trade is increasing. The NGO works to create awareness amongst rural Kenyans and they also work with rangers, police and judicial systems about how to protect pangolins.

Pangolins have also traditionally been hunted for their meat, which is seen as a luxury dish in parts of Asia and Africa. As the middle classes in Sub-Saharan African expand, many organisations are worried that the meat will remain a status symbol, increasing pressure on pangolin populations.

“In Southern Africa, trading in live pangolins is common”, says Professor Jansen. “Anyone who appears to have wealth can be approached and asked if they want to buy a Temminck’s [an African Ground pangolin] for a huge amount of money.”

Although the African continent only this month passed the one million mark for confirmed coronavirus cases, while the United States alone has over 5 million cases, the economic consequences have been uneven and severe.

Nigeria expects its economy to have contracted by 6.1 per cent in the second quarter of this year, with unemployment rising to 27.1 per cent. South Africa’s GDP crashed 40 per cent in the same time frame, according to its central bank. Poverty and desperation are likely to play a large part in pangolin poaching.

“Poaching for survival has absolutely increased,” says Professor Jansen. “Nine out of 10 poachers that we catch are financially destitute and have turned to crime. And the guys that do jail terms tend to be non-South Africans from very poor African countries. The real criminals are the guys on top paying them.”

Pangolins are territorial animals that tend to stay within a reasonably small area, that they demarcate with their urine and faeces. Locals will often be familiar with their movements and burrows.

“The word is out on the radio, on social media, that you can get rich quick if you sell a pangolin,” adds Professor Jansen. He asks that The Independent does not publish the market value of a live pangolin in Africa, “or every second person will be out on the hunt”.

A rural dweller, driven to desperation by their economic conditions, might go out to search for pangolins in burrows to sell to local traders. They may use additional tools including dogs to help them find pangolin.

When threatened, pangolins curl up into an armoured ball – a tactic that is effective against predators such as lion or hyenas, less so against humans capable of picking them up. “This effective defence mechanism that has protected pangolin against predators, has made them extremely vulnerable to poaching by humans,” adds Dr Okell.

Professor Jansen explains that in Southern Africa, the poacher might then attempt to sell the live pangolin to anyone they perceive as wealthy, approaching tourists, farmers and Asian expats in urban areas.

A middleman might take on the pangolin, in which case he will discreetly advertise to clients that he has a pangolin for sale. The animal is typically stored in a cage and force fed before being weighed.

Pangolins become extremely stressed in captivity and can die after just a few weeks from organ failure. Their diet of ants and termites is difficult for captors to imitate.

In central Africa, they are more likely to be killed and sold for meat according to Professor Jansen, often by being bludgeoned to death or boiled alive.

It is then boiled for two minutes in water, before a trader runs a knife across its body to remove its scales, which are kept aside for the Asian trade. The carcass is then gutted and sold as bushmeat, often at a market.

The African Wildlife Foundation estimates that over 2.7 million African pangolins are poached every year. None of the wildlife experts The Independent spoke to were able to estimate by how much pangolin poaching has increased or decreased overall since the start of the pandemic.

“We are all so focused on megafauna [large animals], but we’re losing 25-30 smaller species per day”, says photographer Brent Stirton.

“Pangolins are charismatic, capable of forming relationships with humans, and they’re being killed in massive numbers”, adds Stirton. “It’s unchecked consumption. It doesn’t make sense to me.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks