‘Largest ever’ methane leak detected at Russian coal mine

Satellite observations reveal leak of potent greenhouse has carbon footprint equivalent to five coal-fired power stations

A Russian coal mine has been named as the source of the biggest methane leak ever detected.

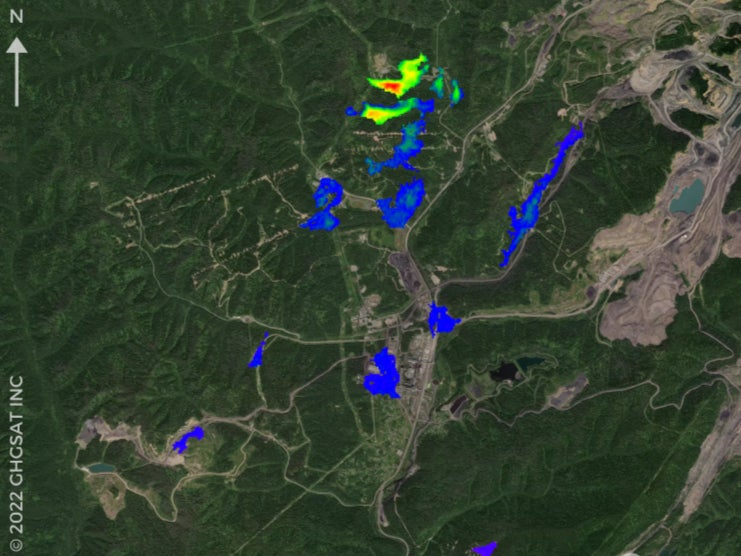

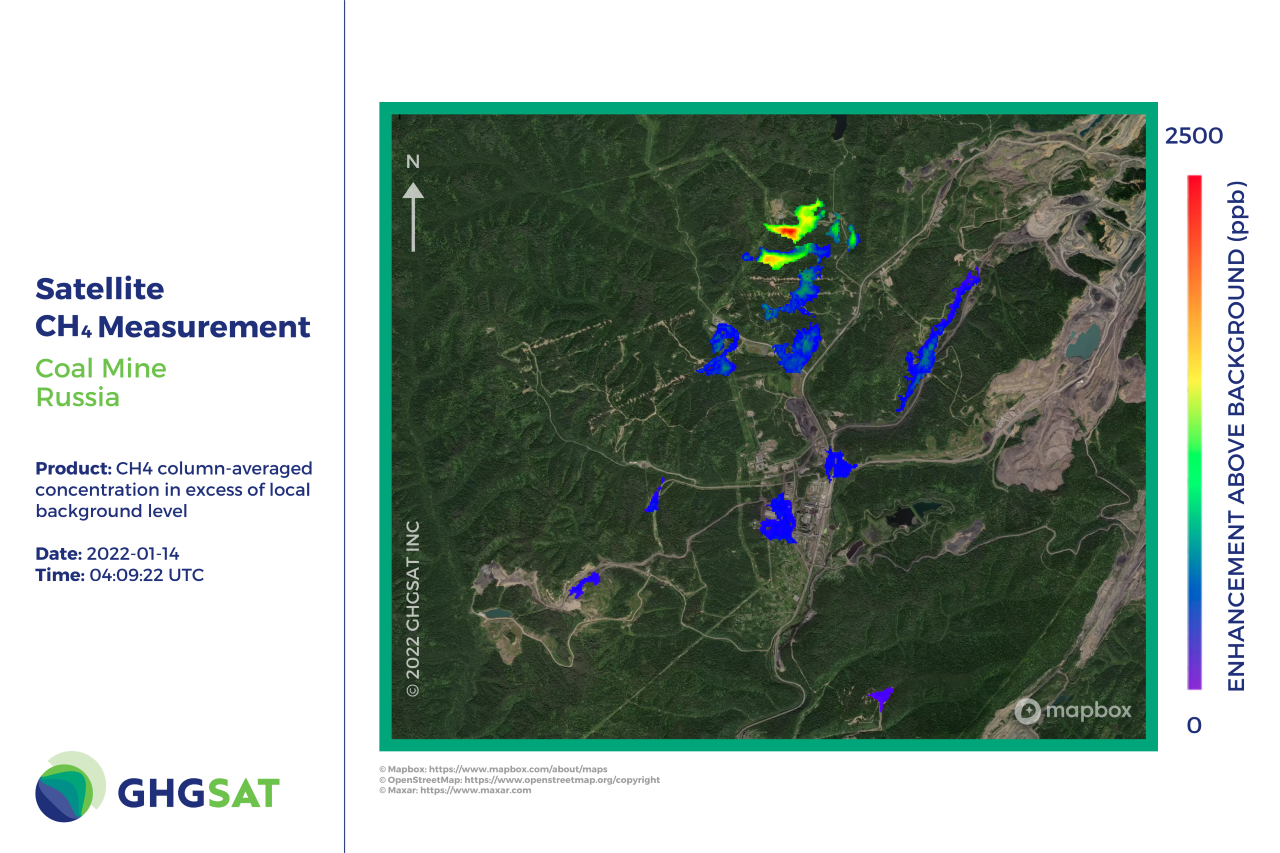

New satellite observations show Raspadskya mine, in central Russia’s Kemerovo Oblast, has 13 separate methane plumes leaking massive amounts of the explosive greenhouse gas in one of largest "ultra emission" events ever traced to a verified source.

Raspadskya is Russia’s largest coal mine and opened in 1973.

According to Canadian company GHGSat, which provides the UN with emissions data and works with the European Space Agency, the mine is leaking 90 tonnes of methane every hour.

If the total rate of release observed by the satellite was sustained over the course of a year, the mine would emit 764,319 tonnes of methane, which GHGSat said was enough to power 2.4 million homes and would have a climate impact equivalent to the CO2 produced by five coal-fired power stations.

The researchers said repeated observations of the region suggest the underground mine consistently expels large quantities of the methane, which has a climate-warming potential around 84 times greater than CO2 over 20 years.

Brody Wight, director of energy, landfills and mines at GHGSat, told The Independent new satellite-based detection of methane leaks was helping to identify major leaks of the potent greenhouse gas around the world.

He said: "Satellite observations have fundamentally shifted our understanding of methane emissions. Previously, recording methane levels involved a person going to a site and pointing a gas detector in the general direction of a suspected source and hoping the wind was not blowing too hard.

“For this reason, millions of methane emitting sites, such as gas wells, compressors, pipes, landfills and mines were left unchecked. Many still are."

But he described the technology as "a game changer".

Mr Wight said GHGSat’s discovery of a massive leak in Turkmenistan in 2018 helped "put methane on the map".

"At Cop 26 the gas was top of the agenda as it is recognised that we have the means to address many of the sources of methane (around 60 per cent of methane emissions are man-made) and given its 10 year half-life, cutting methane emissions is one of our best options for slowing the rate of global warming,” he said.

The scale of the Raspadskya emissions exceeds that of any previous, directly attributable "ultra emission" event, GHGSat said.

The largest man-made methane release previously detected occurred at an underground natural gas storage facility in Aliso Canyon, near Los Angeles, in October 2015.

Estimates put the rate of methane release as high as 58 tons per hour. The carbon footprint of the leak, which took four months to fix, was greater than that of BP’s Deepwater Horizon disaster.

Mr Wight added: "[Total] emissions from mines could be at similar levels to those from oil and gas production. They are also under-reported so we don’t know what the true situation is. Crucially, methane emissions don’t stop when a mine is shuttered. This is an issue we will face even as we one day transition away from coal."

At Raspadskya mine, the releases could be safety related, GHGSat said. The gas is an unavoidable bi-product of mining, with pockets of the gas released as seams are opened.

In May 2010, 66 people were killed at the mine in an explosion and collapse caused by a build-up of methane within its 220 miles of tunnels.

GHGSat has alerted the mine’s operators to its findings.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks