The Big Question: What do we know about the human brain and the way it functions?

Why are we asking this now?

Scientists this week announced that they had succeeded in communicating with a man thought to be in a vegetative state, lacking all awareness, for five years following a road accident. Using a brain scanner they were able to read his thoughts and obtain yes or no answers to questions. They asked him to imagine playing tennis if he wanted to answer yes and to imagine walking through his home if he wanted to say no. By mapping the different parts of the brain activated in each case with the scanner, the scientists were able accurately record his reponses.

What does this tell us about the brain?

That it may still be functioning, generating thoughts and awareness, even when there is no outward sign of consciousness at all. Previously, the only way of telling if someone had any degree of consciousness was by observing how they responded to visual, auditory, tactile or noxious stimuli. If there was no response they were presumed to be in a vegetative state. In vegetative state patients, the eyes are open and they follow the normal cycle of sleeping and waking but they show no sign of being aware of their surroundings, hovering half way between consciousness and unconsciousness. In this patient, the brain scanner showed he was aware even though he showed no outward sign of being so.

How does this discovery fit in with our existing knowledge of the brain?

The brain is our most complex but least understood organ. We can name its parts but our knowledge of what each part does, or how, is rudimentary. Yet it is also critical to our place in the world.The human brain is about three times larger than the brain of chimps for our body size. It is this immense growth of the human brain during the few million years of evolutionary history that distinguishes us from the animal kingdom and determines the uniquely human traits such as language, consciousness and creativity.

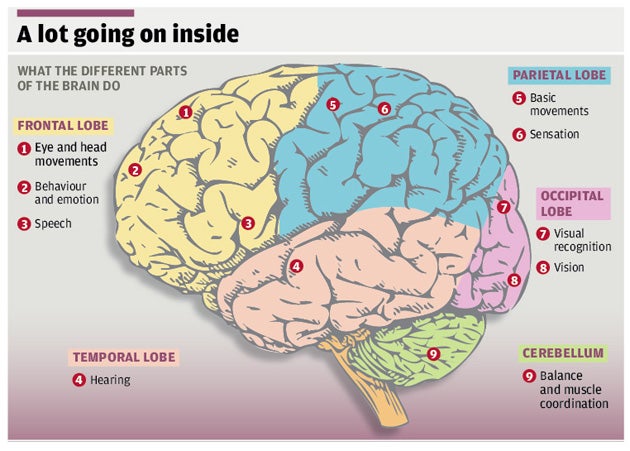

Do the parts of the brain have different functions?

Yes. When rail worker Phineas Gage blew a hole in the front of his brain while tampering with explosives in 1848, he provided one of the earliest insights into how the organ worked. The explosion drove a rod through his cheek and out through the top of his head, causing him to lose the sight of his left eye but, remarkably, little other damage. However, his personality changed dramatically and from being a conscientious, polite and thoughtful man, he became rude, reckless and socially irresponsible. Damage to several areas of the brain involved in feeling and thinking can affect moral judgement but this was the first evidence that the frontal lobe played an important role in personality.

Can the brain's function be affected from outside?

This is a common belief among people suffering from paranoia associated with mental illness. But it happens to be true. Using a technique known as transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), it is possible to temporarily stun a part of the brain, for example that which controls speech, rendering the individual unable to utter familiar words. Using a paddle placed on the head and focusing the TMS on Broca's area of the brain at the back of the left frontal lobe, it is possible to halt speech in mid flow. Subjects report having the words "right there" in their heads but unable to make them "come out."

Does the brain behave differently in different people?

Yes. There is a striking difference in the brains of musicians who play from a score in front of them and those who improvise. Brain-imaging studies have shown that the frontal lobes are activated when musicians are reading the notes but turn off in improvisation, allowing ideas to "float". Studies of the brain have raised the possibility that personality may be "visible" from the activity in different brain areas. At the crudest level, a person with a "sensitive" brain – one that produces more activity in response to a mild stimulus – are less likely to indulge in sensation-seeking or adrenaline sports than those with "insensitive" brains, who need a lot of stimulation to produce the same level of excitement.

Does the brain develop through childhood and adolescence?

It was once accepted currency among neuroscientists that, after the initial reorganisation of the brain's neural circuits in very early childhood, development stopped. The organ remained much the same for the rest of a person's life – save for a gradual loss of brain cells. That view has changed. Scientists now realise that the teenage brain undergoes the same sort of radical re-development seen in the rest of the body. Fatty insulation grows around the neurons increasing the speed of transmission a hundredfold. And the synapses that link the neurons grow and are pruned back in a process considered critical to intellectual maturity.

Can thoughts be made to move things?

Yes. Companies are developing brain computer interfaces to allow severely disabled individuals who have no physical capacity to control their enviroments. Based on the EEG (electroencephalograph) machine they pick up brain signals which trigger on-off switches. To generate right-brain signals, the individuals watch a computer screen and attempt to move an object across it, using the power of thought alone. If they succeed, the object moves in the desired way, the switch is thrown – and the fan or TV comes on. Ultimately, the technique may be used to send emails and offer faster means of communication.

Does the brain contain a God-spot?

Some scientists believe the human brain is programmed for religious experience and this explains why religion is a universal human feature that has encompassed all cultures throughout history. They say there is not one but several areas of the brain that form the biological foundations of religious belief. In a study last year researchers used an advanced brain scanner to show that people of different religious persuasions and beliefs, as well as atheists, all tended to use the same electrical circuits in the brain to solve a perceived moral conundrum – and the same circuits were used when religiously inclined people dealt with issues related to God.

Do brainier people have bigger brains?

Brains tend to vary little in size, but there are exceptions. Jonathan Swift, the author of Gulliver's Travels, had a brain which weighed an enormous 2kg when he died in 1754, while the brain of Ivan Pavlov, the Russian physiologist who discovered the Pavlovian response, weighed barely 1.5kg. There is no link between size of brain and intellect but other features may be important.

Einstein's brain, removed after his death, was missing part of a groove that runs through the parietal lobe. The area affected is concerned with mathematics and spatial reasoning and it is thought the missing groove may have allowed neurons in that area to communicate more easily. If so, it could account for his extraordinary talent.

Does study of the brain tell us about the person?

Yes...

*Damage to parts of the brain such as the frontal lobes has the effect of altering the personality

*People with particular skills show activity in different parts of the brain

*Our brains are what distinguish human beings from members of the animal world

No...

*Being able to answer yes or no to questions is not the same as being fully aware

*Having awareness is not the same as having a biographical life with feelings, thoughts and memories

*A lot more goes into forming the human personality than a mere set of neurons and synapses

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies