How to still build muscle on a plant-based diet

Gym culture still treats meat as a badge of strength – and masculinity – something that former semi-pro footballer Jeffrey Boadi once believed, too. Now stronger and entirely plant-based, he tells Hannah Twiggs what really fuels muscle

For years, the shorthand for strength has been simple: chicken breast, rice, broccoli, repeat. In gyms across the country, protein has been treated less like a macronutrient and more like a moral code, with meat its most visible symbol. To lift heavy was to eat heavy. Preferably animal.

Jeffrey Boadi once believed that, too. “I had such a visceral reaction,” he tells me of a friend who mentioned trying a plant-based diet while training. “I was like, ‘How are you going to do that?! There’s no way you could do that. I would wilt away.’”

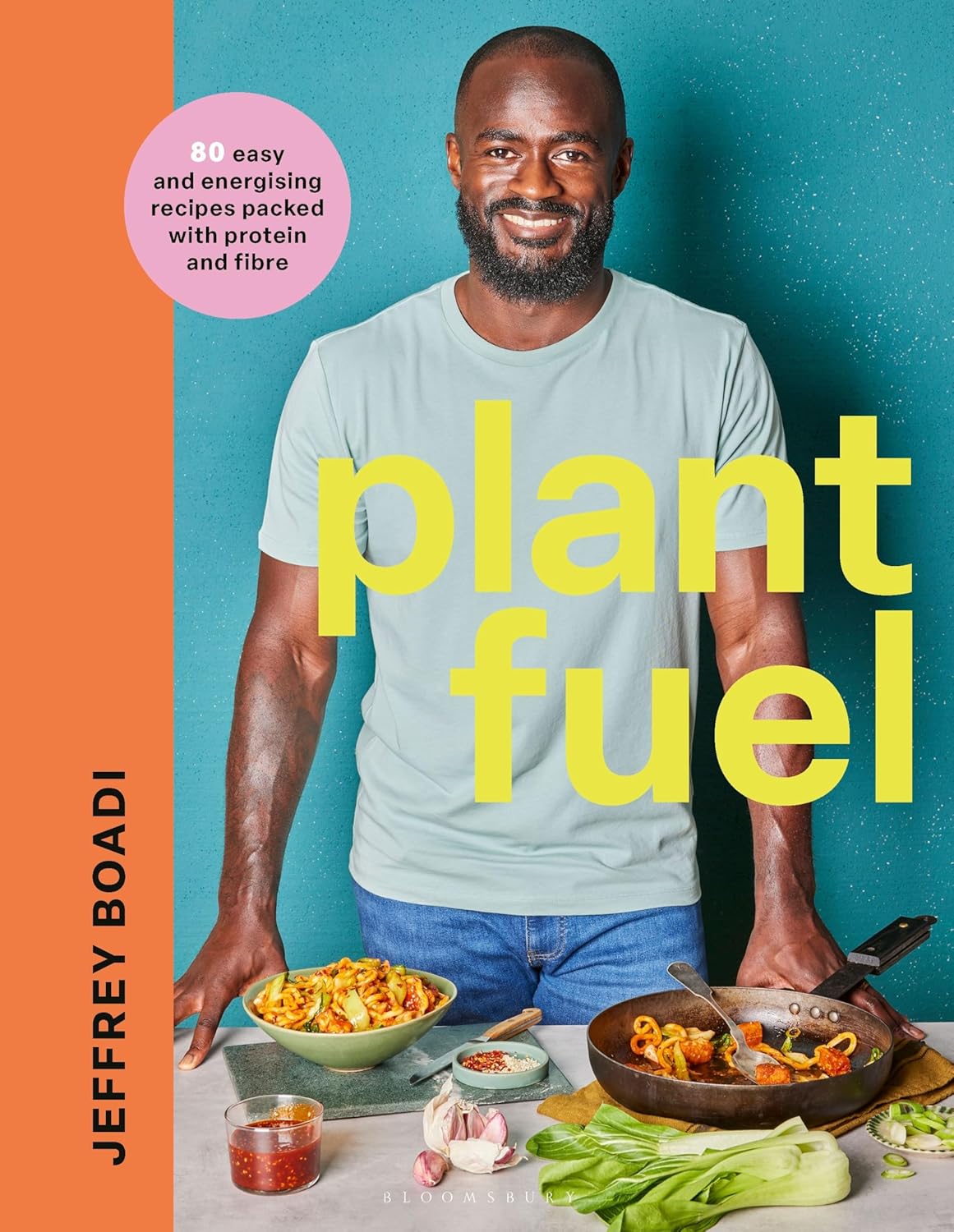

Eight years later, Boadi is heavier, stronger - and entirely plant-based. He’s gone from 84kg to 95kg, lifts regularly and has just released Plant Fuel, a cookbook built around high-protein, whole-food plant-based eating. If the idea of a “vegan gym bro” still sounds like a contradiction, he’s living proof that it isn’t.

Boadi’s credibility matters here. Before Instagram, before recipes, before wellness discourse, there was football. He played semi-professionally in the UK, and trained in the US while trying to break into Major League Soccer, then in Norway and Austria. Sport wasn’t a lifestyle add-on; it was the axis around which everything else turned.

At the time, his nutritional knowledge was basic but familiar. “The extent of my experience and knowledge of nutrition was meat equalled protein and milk equalled calcium,” he says. Like many athletes, he ate for function rather than curiosity. Meat on a plate, carbs on the side, job done.

That changed in 2017 after his sister recommended he watch What the Health, a documentary exploring the link between diet and disease. He’s careful to caveat its influence now: “I don’t think many people should base their dietary changes off a single documentary.” But for him, it was catalytic. He watched it twice in one day and switched to a plant-based diet overnight.

The first two weeks felt transformative. “My sleep was amazing. I was sleeping so much deeper. I had more energy. I felt lighter. I felt like I had more mental clarity as well.” But the early months weren’t flawless. The biggest mistake, he admits, was under-eating.

“When you switch to a plant-based diet, you actually have to eat a greater volume of food,” he says. Used to the calorie density of meat and dairy, he initially lost weight. “I actually lost a kilo or two in those early stages.” The fix wasn’t complicated, just intentional: bigger portions, better structure and an understanding that plants need space on the plate.

That learning curve now underpins the way he eats and trains. Rather than obsessively tracking macros, Boadi works from awareness. “If I have 200 grams of tofu, I know that in that block I’m going to get maybe 38 grams of protein,” he explains. Add quinoa, greens, fats, fermented foods, and the numbers quietly take care of themselves.

The lingering scepticism around plant-based muscle building usually circles back to protein. Boadi is direct about it. “It’s not so much about the source of it,” he says. “Yes, we need protein to build strength, to recover, to be well, etc, but you can get that from plant-based food.”

Tofu, tempeh, lentils, beans, edamame, hemp seeds and seitan form the backbone of his diet, not as substitutes, but staples. Some, like edamame, are still oddly overlooked. “You get like 13 grams of protein in a cup of edamame,” he says. Soy, he adds, is “very well absorbed” and ranks highly for protein quality. Seitan, wheat gluten with a long history as a meat substitute in China that dates back to the sixth century, delivers “upwards of 25 grams of protein per 100-gram serving”.

Protein powders have their place, too, but as tools rather than crutches. “Is it essential? I wouldn’t say it’s essential,” he says. “But it can be beneficial and it can be convenient. Sometimes, whole foods might not always be practical.”

What sets Boadi apart from most gym-diet conversations, though, is where he places the real advantage of eating this way. For him, muscle isn’t built by protein alone. Recovery is the missing piece.

“When [studies] compare an omnivorous diet to a vegan diet over 12 weeks, there is no significant difference in muscle strength and muscle mass,” he says. What does change, in his experience, is how the body handles training stress. “One of the biggest factors wasn’t even the protein side of things … it was actually the increase in really antioxidant-rich foods.”

Berries, leafy greens, sweet potatoes and colourful vegetables became daily fixtures. “What they do is help with inflammation and reduce oxidative stress,” he explains, a constant undercurrent when you’re lifting weights and tearing muscle fibres. He points to research on blueberries in particular, noting their role in reducing inflammation and helping restore muscle strength after training.

This is where fibre enters the conversation, a nutrient gym culture has largely ignored. Boadi doesn’t oversell it. Instead, he frames fibre as a recovery amplifier. Low fibre intake, he says, contributes to low-grade inflammation. Certain fibres, like pectin from stewed fruits, are fermented by gut bacteria to produce short-chain fatty acids such as butyrate, which “helps to reduce inflammation and improve the integrity of the gut lining”.

“That inflammation piece is really important,” he says. “Being able to recover well is one of the best things in terms of being able to increase your training load and not have to miss out on training or feel fatigued.”

The implication is subtle but important: fibre doesn’t build muscle directly, but it helps you show up, session after session, without burning out. In a culture obsessed with peak performance, Boadi is more interested in sustainable strength.

Fibres fermented by gut bacteria helpt to reduce inflammation and improve the integrity of the gut lining”

That outlook also shapes his stance on veganism itself. He’s clear-eyed about its recent rise and fall, and critical of what followed. “That peak of veganism in 2019 and 2020 led a lot of companies to start producing a lot of these ultra-processed vegan products,” he says. “Because there was this general perception that because it’s vegan, it must be healthy.”

He doesn’t mince words about the trade-off. “I would put stock in the long-term health outcomes of a health-conscious omnivore versus a junk food vegan. For me, there’s no comparison.”

Fibre intake, he says, remains woefully low – “95 per cent of us aren’t getting the 30 grams a day”. Whether someone eats meat or not matters less than whether vegetables, beans, whole grains and fruit are doing the heavy lifting.

That pragmatism extends to masculinity, too. The idea that meat equals manhood has always felt flimsy to him. “How does eating meat truly align with being a man?” he asks. “I think being a man and healthy masculinity has so many other kinds of facets to it, in terms of family and wanting to be an upstanding citizen and being a decent human being. I’m not sure where meat comes into the equation.”

Culturally, his Ghanaian background has made the transition easier than many might assume. “Whenever I go to visit my mum’s church or when my wife and I go and visit our family in Ghana, they probably do think it’s a bit weird,” he says, but “in Ghana, a lot of the foods are very plant-rich anyway.” For example, there’s yams, a staple in West African cuisine; waakye, rice cooked in hibiscus leaves and mixed with black-eyed beans; hausa koko, made from fermented millet porridge; and plantain, prekese and porridges. “It’s quite easy to be vegan,” he says. “I could just eat plantain and beans all day and be happy.”

These days, Boadi is less interested in peak gym numbers than in staying strong for life. “I’m just trying to be healthy for life,” he says. “You know, get to my 60s, 70s, be able to feel good, be able to run around with my grandkids. I’ve reduced my risk of disease now and for the future.” He’s not dogmatic about it either. Ninety per cent plant-based, he says, is still a win.

The broader point is harder to argue with. You don’t need to give up the gym to give up meat. You don’t need to shrink, soften or sacrifice strength. You just need to rethink what fuels it.

Ghanaian red red stew

“Being of Ghanaian heritage meant I absolutely had to include this dish for you to try. I’ve got fond memories of enjoying it as a child at home and whenever I visit Ghana these days, I pretty much have it every day. I love it – and so will you!”

Serves: 4

Protein: 16g per serving | Fibre: 16g per serving

Prep time: 20 minutes | Cook time: 50 minutes

Ingredients:

75g red bell pepper, chopped

250g tomatoes, quartered

1 medium onion (150g), halved (one half finely diced, the other quartered)

70g carrot, chopped

3 tbsp palm oil

½ scotch bonnet (optional)

300ml aquafaba (water from the canned beans)

3 garlic cloves, minced

1 tbsp chopped fresh ginger

1 tsp ground cumin

1 tsp curry powder

1 tsp ground coriander

1 tsp cayenne pepper

1 bay leaf (optional)

1 tbsp tomato paste

2 vegetable stock cubes, crumbled

3 cans black-eyed beans (keep the water, rinse the beans)

4 ripe plantains

3 tbsp avocado oil

2 medium avocados (300g), sliced

Sea salt and black pepper, to taste

Pinch of chilli flakes, to garnish

Method:

1. Preheat the oven to 200C/fan 180C/gas mark 6.

2. Add the red pepper, tomatoes, onion quarters and carrot to a roasting tin. Drizzle with 2 tablespoons of the palm oil, then sprinkle with salt and pepper and toss to coat evenly.

3. Roast for 20-25 minutes until the vegetables are caramelised and tender.

4. Add the roasted vegetables, scotch bonnet, if using, and 200ml of the aquafaba to a jug blender. Blend to make a sauce and set aside.

5. In a large saucepan, heat the remaining 1 tablespoon of palm oil. Add the diced onion and cook for about 2 minutes until translucent.

6. Add the garlic, ginger, spices and bay leaf, if using. Sauté for 1-2 minutes.

7. Pour the vegetable sauce into the pan, then add the tomato paste, stock cubes, black-eyed beans and remaining 100ml of aquafaba.

8. Mix well and cook for about 10 minutes over a low heat while you prepare the plantain.

9. Peel, halve and slice the plantains lengthways, then sprinkle with salt and toss in a mixing bowl.

10. Heat the avocado oil in a medium frying pan over a medium heat. Fry the plantain for about 15-20 minutes, flipping occasionally until golden brown.

11. Alternatively, coat the plantains with a little palm oil and salt, then bake them in the oven at 180C/fan 160C/gas mark 4.

12. Once the plantain is ready, use a potato masher to mash the beans slightly to make the stew creamy.

13. Serve the stew with either baked or fried plantains and avocado slices, garnished with chilli flakes.

Gochujang tofu stir fry

“This dish is fast fuel at its finest! Gochujang has a spicy, sweet umami flavour and I’m a bit addicted to it. You’ll be surprised at how quick and easy this dish is to make – it has layers of flavour and plenty of protein.”

Serves: 2

Protein: 34g per serving | Fibre: 7g per serving

Prep time: 10 minutes | Cook time: 15 minutes

Ingredients:

280g firm tofu

2 tbsp cornflour

200g udon noodles

2 tbsp extra-virgin olive oil

250g pak choi, sliced

2 spring onions, sliced

Pinch of chilli flakes, to garnish

For the sauce:

4 tbsp gochujang paste

4 tbsp toasted sesame oil

2 tbsp agave nectar

3 garlic cloves, minced

2 tbsp sesame seeds

3 tbsp soy sauce

½ tsp black pepper

Method:

1. Press the tofu for at least 10 minutes to remove excess water, then cut into bite-sized pieces.

2. Transfer the tofu to a bowl and coat it in the cornflour.

3. Cook the udon noodles according to the packet instructions.

4. At the same time, heat the olive oil in a medium to large wok-style pan, then fry the tofu over a medium to high heat for 6-8 minutes, or until all the pieces are light golden brown.

5. Remove the pan from the heat, set it aside and wipe away any remaining oil from the pan.

6. When the noodles are almost cooked, add the pak choi to the noodle pan for 2-3 minutes to lightly blanch and wilt.

7. Once ready, drain the noodles and pak choi in a colander, and briefly run them under cool water. Remove as much water as possible.

8. In a small bowl, whisk together all the sauce ingredients.

9. Coat the tofu with half of the sauce, then return the pan to a medium heat.

10. Add the noodles, pak choi, spring onions and the remaining sauce to the pan, mixing well to ensure all the ingredients are coated. Fry for 2-3 minutes until hot.

11. Garnish with a sprinkle of chilli flakes and serve.

Mango and cashew cheesecake

“This tropical mango dessert has a tasty ginger biscuit base and a luxuriously smooth cream filling. It is a rich and refreshing dessert that I can guarantee you’ll be making time and again!”

Serves: 8

Protein: 9g per serving | Fibre: 4g per serving

Prep time: 45 minutes | Chill time: 3 hours (plus soaking the cashews)

Ingredients:

For the base:

100g rolled oats

80g ginger biscuits

50g pumpkin seeds

8 medjool dates, pitted

4 tbsp coconut oil, melted

For the filling:

100g cashews

1 tbsp agar agar powder

150g of fresh mango, puréed

3-4 tbsp maple syrup (adjust to taste)

½ lemon, juiced

1 tsp vanilla extract

200g silken tofu

200ml canned coconut cream

For the topping:

1 tbsp agar agar powder

250g fresh mango, puréed

4 limes, juiced

3 tbsp maple syrup

Method:

1. Soak the cashews for the filling for at least 2 hours (or in just-boiled water for 10 minutes), then drain.

2. To make the base, combine the rolled oats, ginger biscuits, pumpkin seeds and pitted dates in a food processor.

3. Process until the mixture becomes a sticky, crumbly texture.

4. Add the melted coconut oil and process again to combine.

5. Press the mixture firmly into the base of a lined springform cake tin measuring either 18 or 20cm in diameter. Chill in the fridge while you prepare the filling.

6. In a small saucepan, vigorously whisk the agar agar powder, mango purée, maple syrup, lemon juice and vanilla extract.

7. Heat for 3-5 minutes until the mixture simmers.

8. Drain the tofu and add to a jug blender with the coconut cream and soaked, drained cashews. Blend until completely smooth and creamy.

9. Add the warm agar agar mixture and blend again.

10. Pour the mixture over the chilled base and spread evenly.

11. Return to the fridge to set for at least 2 hours (although overnight is best).

12. For the gel topping, combine the agar agar powder, mango purée, lime juice and maple syrup in a small saucepan and simmer for 2-3 minutes, stirring continuously.

13. Allow the gel to cool, then gently pour it over the set cheesecake. Chill in the fridge for at least 1 hour until the topping firms up.

‘Plant Fuel’ by Jeffrey Boadi (Bloomsbury, £22)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks