Like Robbie Williams I was diagnosed with adult ADHD – just don’t call it ‘fashionable’

As more famous people share their mental health problems, it should make it easier to talk about your own, says Kat Brown. But it becomes a lot harder to admit to a diagnosis when others just think you’re jumping on a bandwagon...

When I saw a headline in which the psychotherapist and author Philippa Perry called ADHD “fashionable”, my heart sank. I admire Perry immensely. I gave her book on parenting to my brother when he had his first child, and I follow her on Twitter/X for all her brilliant advice. But I had just written a book on adult ADHD diagnosis called It’s Not a Bloody Trend, and here was one of the people I would have least expected to show just why I had given it that title.

Perry’s full quote, that having ADHD-like symptoms doesn’t mean you have it, and that labels can give people an excuse not to take responsibility, is absolutely fair. But it was her suggestion that ADHD was somehow trend-led, or “the mental health term on everyone’s lips”, taking over from “bipolar disorder that was once the ‘fashionable’ condition to have” that made it so upsetting to many people with ADHD because getting a diagnosis can be intensely hard, as hard as living in chaos without one. And I should know because three years ago, aged 37, I was diagnosed with combined type ADHD in 2020, after spending years struggling with depression, suicidal ideation, anxiety, eating disorders, insomnia, and an overwhelming sense that there was something deeply wrong with me.

Nobody’s brain is the same, as I have discovered while researching my book, It’s Not A Bloody Trend: Understanding Life as an ADHD Adult, which I have written as my response to the kinds of attitudes that Perry has given voice to. Not for nothing was the 1993 hit self-help book for adults with ADHD titled You Mean I’m Not Lazy, Stupid, or Crazy?!

I usually write about arts and culture, but I am full of fun ADHD facts now. Was adult ADHD really only recognised in the UK in 2008? No, Europe’s first adult ADHD clinic was founded in south London in 1994. Does trauma cause ADHD as the Panorama documentary that aired in May suggested? A big no from the consultants I interviewed – ADHD symptoms need to have been present since before the trauma to form a diagnosis. Are private clinics really terrible? Yes and no – you should always look for a psychiatrist who also works in the NHS alongside their private practice to ensure they are working to clinical standards.

I also wanted to write this book because I was so fed up with seeing pieces by older industry colleagues about how everyone thinks they’re a bit ADHD, that it’s not real and that everyone wants something wrong with them. Historically, the generation above has always sniped at the young, but it’s particularly odd when you consider that it’s largely older people being diagnosed with ADHD in adulthood.

Middle-aged parents are one such group, often taking their kids along for a diagnosis only to see themselves in the criteria. One responder to my research questionnaire was a civil servant in her sixties. She told me of her lifelong struggle to focus on tasks; a daydreamer, she was full of ideas she didn’t follow through. She didn’t think she was hyperactive, but her racing thoughts told another story. Like so many people looking for answers, she had launched into a journey of discovery to diagnosis.

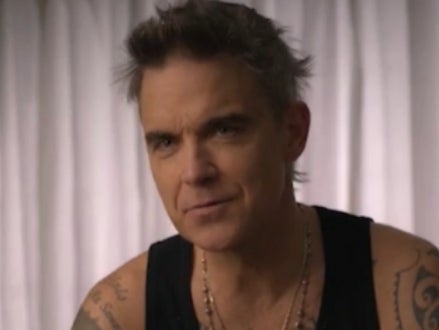

Last weekend, Robbie Williams, 49, told Caitlin Moran that he had “dyspraxia, dyslexia, ADHD, neurodiversity, body dysmorphia, hypervigilance... I am collecting them all, like scout badges.” But any of theses won’t have been necessarily new, just noticed at last, rather than dismissed as personal failings. As he put in his 2006 song, “The 80s”: “School was a laugh/ They didn’t have ADD/ Thick was the term they used for me/ Over and over, repeatedly.”

The trail of addiction, mental health issues, and self-harm is on full display in Williams’s forthcoming Netflix documentary, which is why there is a huge relief in knowing there is a reason behind why you behave like you do.

When I was diagnosed, suddenly everything else fell into place. It helped me to stitch together more than 20 years of struggles with alcohol, coffee, food and even shopping. It explained why my focus and energy levels were all over the place and why I couldn’t have the one specialism at work like everyone else. My family was initially underwhelmed – I was also dealing with unexplained infertility and hip dysplasia at the time, and it was all a bit much – but they have since done their research and are really supportive. When I finally found a medication program that worked and started coaching and therapy through the government’s Access to Work grant, everyone around me could see the stabilising impact this approach had.

I went through the system reporting depression at 18, insomnia at 20, anxiety at 30, and binge eating disorder at 32, but my diagnosis and treatment took years

Philippa Perry later clarified on Twitter, “I’m not saying ADHD doesn’t exist, I’m saying it shouldn’t be an identity, and it shouldn’t be self-diagnosed.” But for many adults, self-diagnosis is the first step to treatment. The chances are they will have seen GPs and mental health practitioners for years without anyone putting two and two together. I had been a frequent flyer at the GP since age 10 when I was diagnosed with epilepsy, which is a common comorbidity with ADHD in children. I went through the system reporting depression at 18, insomnia at 20, anxiety at 30, and binge eating disorder at 32, but my diagnosis and treatment took years. Much of the time, I just assumed I felt this way because I was defective, and so I’d better try five times as hard to pass as a human being as everyone else.

NHS referral now takes an average of three years for both adults and children to be assessed, often longer. In my south London borough, I was told a year, and that still felt too long, so I used my tax savings to go private. People aren’t seeking a diagnosis to label themselves; they are looking for an answer to what’s “wrong” with them. Twenty years later, when I went to see my GP with a folder of evidence, I finally got my answer. Certainly, nobody criticises people coming forward for cancer screenings as “fashionable” because they saw it on Instagram.

Finding the right type and dosage of medication is complicated, and everyone’s reactions will be different

My diagnosis came after a 90-minute consultation with a private doctor who took my full history and talked to my husband and dad. Signs of ADHD will have been evident since at least age 12 in girls, if not earlier – and as my dad didn’t recognise this, and we didn’t have my school reports, I took an additional test that measured my ability to focus. Even when I got my results – combined type ADHD – there was no instant treatment. At the time, I was a year sober from alcohol, so I went through several tests through my GP to ensure I would be a suitable candidate for stimulants. Four months after my diagnosis, I started my first medication, and it took nearly a year to establish the right protocol for me. I was lucky: one woman I interviewed had an additional two-year wait before she could be medicated after her initial NHS diagnosis.

However, it isn’t as simple as knocking back a pill (Ritalin usually gets named here). Finding the right type and dosage of medication is complicated, and everyone’s reactions will be different. There may also be other conditions to consider: I am currently taking a non-stimulant that builds up in my system over time, a longer-release stimulant and a short-release stimulant that both leave my body completely after 12 hours, an anti-anxiety med, and an antidepressant. I don’t take the whole lot every day, but they act as a scaffolding to hold everything together.

While researching my book, I discovered from Professor Philip Asherson, who, with Professor Young, co-wrote the 2008 National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidelines on adult ADHD, that the “gold standard” of treatment should involve medication, ADHD coaching and therapy. As Professor Young herself put it to me, “Pills don’t teach skills.”

People with ADHD need coaching to unpick the unhealthy coping strategies we’ve cobbled together and to find ones that help. Therapy, I believe, is essential for helping us to accept ourselves, for dealing with the grief that can arise from thinking of what life could have been like if we had known our diagnosis earlier. We’re all carrying difficult stuff. Whether it’s a “fashionable” way of thinking or not, the truth is dealing with it makes everything better both for ourselves and everyone around us.

‘It’s Not A Bloody Trend: Understanding Life as an ADHD Adult’ is published by Robinson, 1 February 2024

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks