Mary Ann Sieghart: Why economics and politics don't mix

Walk through the mahogany halls of the historic Hotel Sacher in Vienna, as I did on Saturday, and you can turn into a little salon whose walls are covered in sepia photos of the more celebrated of the Sacher's guests. Tucked away at the bottom is one Rudolf Sieghart, my great-grandfather: bald, stiff-backed, with a resplendent moustache. More notorious than famous by the time he died, he ended up as the Sir Fred Goodwin of his day.

The parallels with today's debt and banking crises are uncanny. In the 1920s, Rudolf was president of Eastern Europe's largest bank, the Bodenkreditanstalt. Its mistake was to grow too fast – both by lending too much to beleaguered businesses and by buying other banks.

By the late 1920s, the Austrian economy was in a dreadful state. Because Austria was on the gold standard, it couldn't devalue, just as it can't now. As a result, Rudolf wrote, "Doing business in Austria became ever more difficult. Industrial firms found it harder to raise new funds. Labour unions, politicians and newspapers began pressuring the banks to fill the gap. They 'had to fulfil an economic duty' of bailing out 'the threatened firms during bad times'."

So the Bodenkreditanstalt did bail out businesses, and eventually it needed a bailout of its own. In 1929, there was a run on the bank. It became the first domino to fall in the banking crisis that precipitated the worldwide Great Depression. The Austrian government refused to rescue it but persuaded its rival the Kreditanstalt to take it over, much as Lloyds was pressured to take over HBOS. This merely postponed the pain until 1931, when there was a run on the Kreditanstalt. This time, the government did bail it out, but the contagion spread to German banks, and then British and American ones too. In rescuing the banks, the governments built up such large deficits that they could not remain on the gold standard. By 1932, Austria, Britain, Germany and some 20 other nations had abandoned it.

As eurozone finance ministers survey today's wreckage, they must wish that they too had the flexibility they used to enjoy outside the euro. Instead, they are stumbling along in what feels like a three-legged race – but worse, because there are 17 members with legs tied together. If a small one falls, the others can just about pull it up again. But once several go down, the whole team crashes to the ground. And if the euro does collapse, internal Treasury modelling suggests that the result would be catastrophic, not just for Continental Europe but for Britain too.

It's not as if the members of the team can even control their pace. For they are held back by their respective voters. And the biggest problem at the moment is that the economics and the politics of the debt crisis are pulling in opposite directions.

The economics demand austerity – or at least as much austerity as can be achieved without seriously squeezing growth. But politically, of course, that is extremely unpopular. In the eurozone, the economics also demand that the richer members subsidise the poorer ones, either directly through bailouts or indirectly by jointly taking responsibility for euro-wide bonds. But politicians will lose their jobs in the richer countries because their voters don't want to have to pay for this, and in the poorer ones because their voters don't like its quid pro quo – that the richer countries will end up dictating their economic policies.

Another problem is that economics and politics move at different speeds. Confidence in the markets can evaporate in a matter of hours, as we saw last week. But try getting 17 parliaments to agree on new funding for the European Financial Stability Facility before it's too late for Italy and Spain.

Markets can be assuaged only if governments move further and faster than investors expect. Yet governments can't move that far and fast without risking huge unpopularity with their voters – and voters will be persuaded of the necessity of doing so only once they have seen the markets' implacable revenge. Millions of Democrat voters accepted that the US deficit needed addressing only once the country had been downgraded from its AAA rating. By then, though, the damage had been done.

The US downgrade will have political effects here too, for it seriously undermines Labour's position on the deficit. Standard and Poor's' justification for the downgrade was that American debt as a percentage of GDP was forecast to carry on rising even after the $2.4trn spending cuts agreed last week. By contrast, it said, Canada, France, Germany and the UK – which are all still rated AAA – are predicted to see their debt-to-GDP ratios falling by 2015.

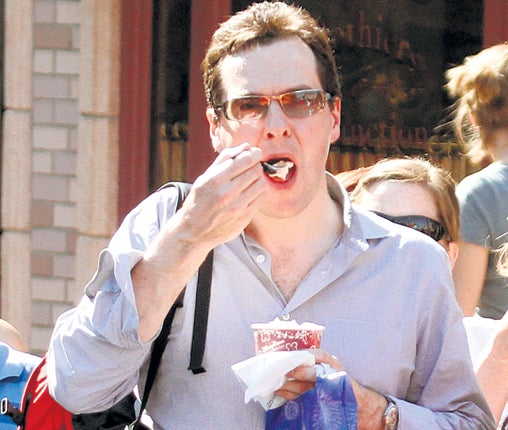

But under Labour's plan to halve the deficit, that ratio would continue to rise. This makes George Osborne's insistence that his austerity measures are vital to retain market confidence rather more convincing. And it makes Ed Balls's worship of President Obama's fiscal expansion now look a little foolish.

For credit ratings are more than symbolic. They underpin that most elusive of economic engines: confidence. We need investors and rating agencies to be confident in our government's determination to bring down the deficit. We need customers to be confident that their money is safe in the bank. And we need big businesses, which are now sitting on piles of money, to be confident enough to invest. Otherwise, as we saw in 1931, the result is disaster.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks