The government must stop demonising the unemployed

When the furlough scheme ends in October, many more are going to be out of work, writes James Moore

Let’s be honest: the latest unemployment figures are a nonsense, at least the ones that are traditionally looked at when they’re rolled out.

The Resolution Foundation actually conducted a detailed analysis showing why, but it was scarcely necessary.

If you consider that there were 9 million or so workers sitting at home and probably feeling worried between March and May, the actual number of people who were unemployed during that quarter comes in at something over 10 million when you add the official number (1.35 million, according to the Office for National Statistics).

Furloughed workers might not satisfy the International Labour Organisation’s accepted definition of “unemployed” (a point that the ONS made), but given that they were mostly inactive and in receipt of state support, isn’t that the position they were effectively in?

A figure more reflective of the reality of the situation is the average weekly hours worked per person. It fell to a record low of 26.6 in the second quarter of the year, some 5.5 hours lower compared with the same period a year ago.

Now it has started to pick up; you would hope that that will continue and that most of those on furlough will be going back to work when Rishi Sunak’s scheme is replaced in October by the much weaker “jobs retention bonus”, which will hand employers £1,000 for every furloughed worker still on the payroll in January – although some firms have said they won’t take it (and good on them for that).

The scale of the crisis – for once, that overused word is an appropriate term for what this country is facing – will be much clearer at that point. Some employers have already started to act: the latest data doesn’t include the thousands of people laid off in recent days by big employers such as Boots and HSBC.

It isn’t all grim. As well as the weekly hours worked starting to pick up in May, self-employed people saw a significant rise in work. The staged reopening of the economy is clearly having an impact.

Jing Teow, senior economist at PricewaterhouseCoopers, sees grounds for optimism in that and in the fact that the sharp decline in vacancies looks to be tailing off.

As she notes, however, the reopening needs to continue and consumers’ wafer-thin confidence must be restored for those gains to be sustained.

And her final point bears close attention: “Reopening the economy comes with risks of a second wave as we’ve seen in other countries and in Leicester. A subsequent lockdown would be a setback for workers.”

That’s quite an understatement.

Some estimates have put the ultimate level of unemployment facing Britain at as much as 4.5 million, which would be unprecedented.

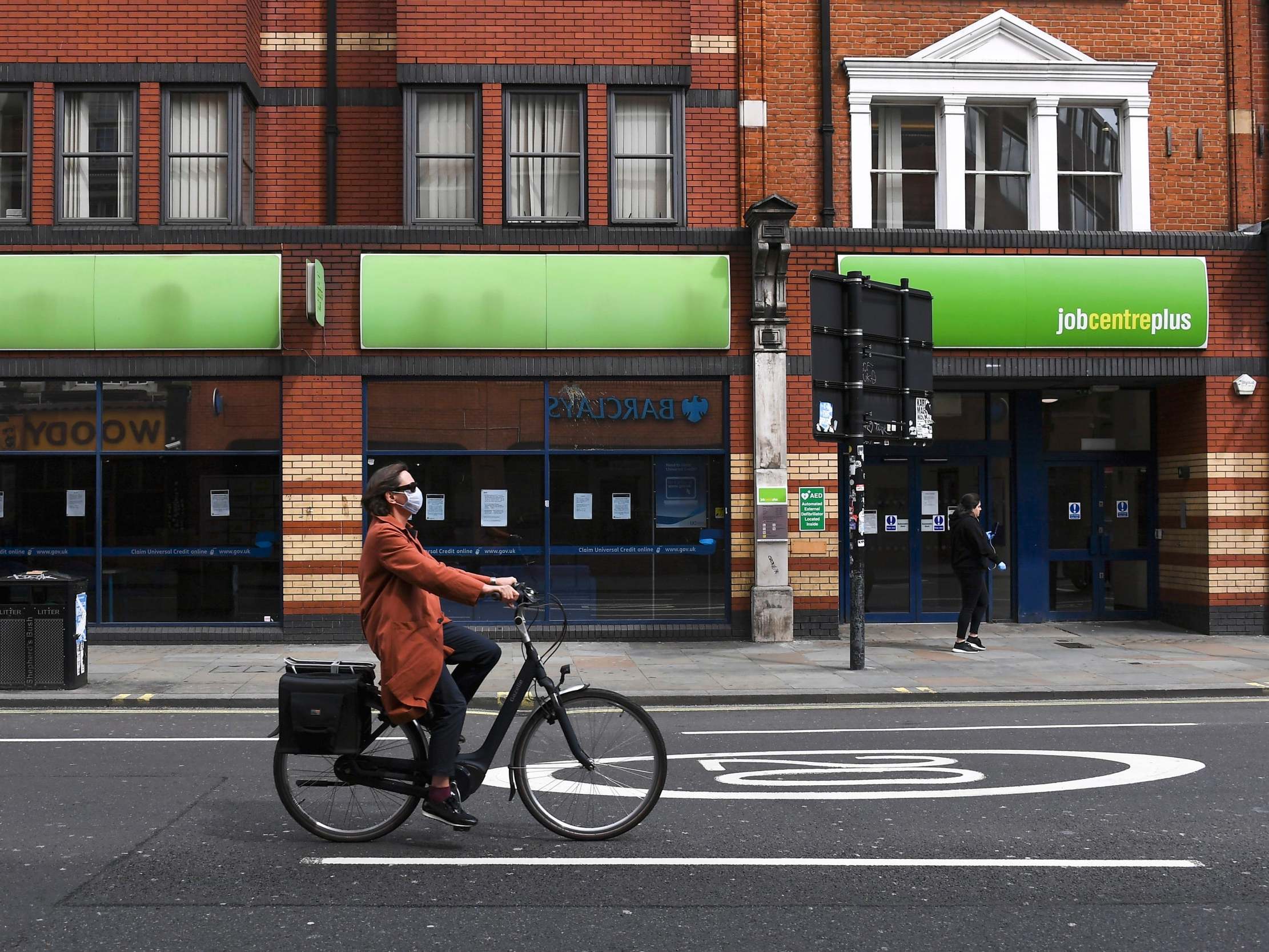

It’s a pity, but probably not terribly surprising, that the government appears not to have thought too deeply about how to handle the challenge that poses, beyond doubling the number of Job Centre Plus staff – which may still leave them overstretched – and restoring the temporarily suspended sanctions regime that universal credit claimants face.

The latter was a particularly unwelcome and unhelpful move. The climate of suspicion that claimants had to deal with before the coronavirus struck was neither fair nor terribly productive. Unemployment is something most of us are probably going to encounter at some point in our working lives, which is why we have a safety net. Accessing it is often a source of shame to people, made all the more so by the way the government treats them when they have to do that.

There is now even more reason to do away with that sort of approach given that millions of people who were employed and clearly wanted to stay that way are going to be thrown out of work through no fault of their own. The government could, and should, pay a price if it continues to insist on demonising them.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks