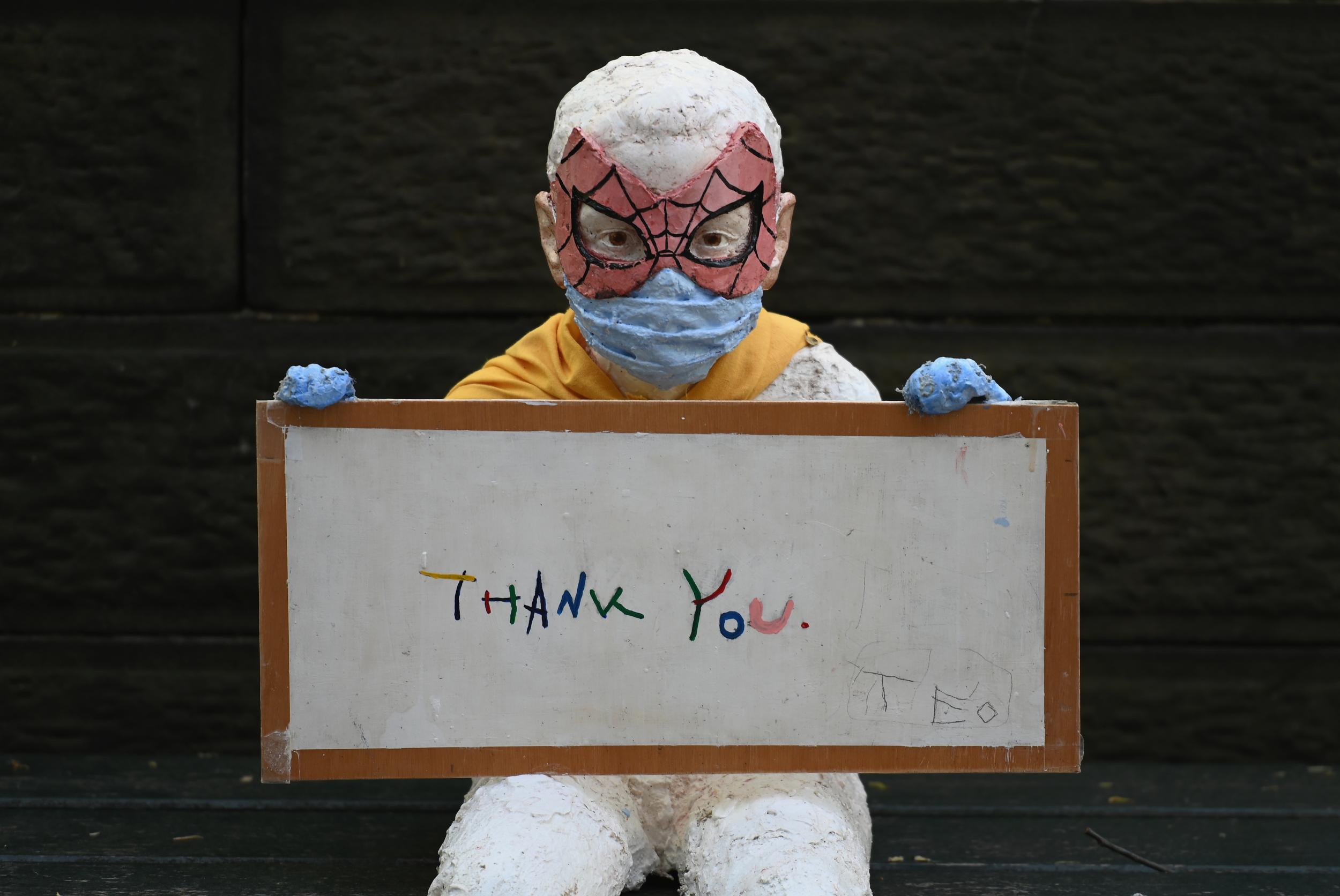

The many and multifaceted ways coronavirus is harming children

From restricting access to food to impacting mental health, experts warn we must act to help youngsters, writes Andrew Buncombe

We were told not to worry about the children.

The coronavirus was not going to harm them. It the was the elderly and infirm we needed to be concerned about. It was they who needed to stay inside.

And indeed, the elderly and those with underlying health conditions were among those first laid low by the disease. It was people aged in their 80s and 90s who were first to perish in clusters such as at the Life Care Centre nursing home in the Seattle suburb of Kirkland.

Yet as the contagion has dragged on, anxious weeks merging into anxious months, mounting evidence has emerged of the pandemic on children, often in ways people may not have assumed.

In terms of the actual deaths of children from the virus, the number in the US and elsewhere has been very low. Recently, there have been reports of a small number of children falling ill with a mysterious illnesses, that has symptoms similar to that triggered by the virus.

Over the weekend, hundreds of paediatric specialists and representatives from the Centres for Disease spoke to discuss the phenomenon, according to the Washington Post. It said hospitals worldwide had identified 100 such cases an around 50 are in the US.

The impact on children of the pandemic and the way countries have responded, stretches beyond physiology.

Experts have warned that the mental health of children is especially vulnerable during these time of lockdown. The ability of some children to access adequate food is also threatened. As with so much else in the United States and elsewhere, the harm is felt most keenly by poor children, and children of colour.

“Like it has with adults, Covid-19 will disproportionately hurt minority children,” Dolores Acevedo Garcia, Professor of Human Development and Social Policy at Brandeis University in Massachusetts, told reporters this week. “We need to say this explicitly, and we need to have mitigation strategies that fully recognise and address these inequities.”

During the briefing, organised by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, an NGO that works on health issues, Ms Acevedo-Garcia said before the pandemic, black children were eight times more likely than white children to live in what is termed a “low opportunity neighbourhood”, and Hispanic children five times as likely. A low opportunity neighbourhood is defined as one that lacks resources and acts to amplify the consequences being poor.

“For example, in very low opportunity, neighbourhoods or children are unable to go to school, often their parents cannot care for them or help them with schoolwork because they hold essential jobs,” she said.

She added: “Children are experiencing distress, disruption, fear and economic insecurity associated with the crisis.”

While some have pointed out the was in which the virus has shown people’s interconnectedness, she said the pandemic had exacerbated inequity among children. She predicted child poverty will increase and its effects will be disproportionately concentrated among minority families and neighbourhoods, where they will struggle to confront trauma, food insecurity, housing instability, and abuse.

Others have raised the alarm about the impact on youngsters. The charity Save the Children has been highlighting how the pandemic has affected children’s lives around the world.

Recently it said around one-in-four children living under lockdowns, are dealing with feelings of anxiety, with many at risk of lasting psychological distress, including depression. Surveys of children and their parents in the US, Germany, Finland, Spain and the UK, found up to 65 per cent of the children struggled with boredom and feelings of isolation.

“People who are outside regularly have lower activity in the part of the brain that focuses on repetitive negative emotions,” said Anne-Sophie Dybdal, a senior advisor to the charity. “This is one of the reasons children can slide into negative feelings or even depression during the circumstances they are living in now.”

In Los Angeles, a city that has some of the wealthiest and poorest neighourhoods in the nations, experts have warned the full impact of the pandemic in the mental health of children, will not be seen for some time.

“We’re only going through the first wave of the disaster,” Dr Curley Bonds, chief medical officer for the LA County department of mental health, told the Los Angles Times. “This is the equivalent of people waiting on rooftops to be saved after Hurricane Katrina.”

Some of the most stark warnings have come from the United Nations.

A report published last month warned the pandemic was “potentially catastrophic for millions of children”. It said the impact would be felt differently in different countries.

“All children of all ages and in all countries are affected. However, some children are destined to bear the greatest costs.”

It said those most struck would be those youngsters living in refuge camps, war zones, detention centres and the poorest parts of cities.

“We must act now on each of these threats to our children,” said UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres.

“Leaders must do everything in their power to cushion the impact of the pandemic. What started as a public health emergency has snowballed into a formidable test for the global promise to leave no one behind.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments