Book of a lifetime: The High Hill of the Muses by Hugh Kingsmill

From The Independent archive: Michael Holroyd on an inspired mingling of biography, landscape and literary criticism

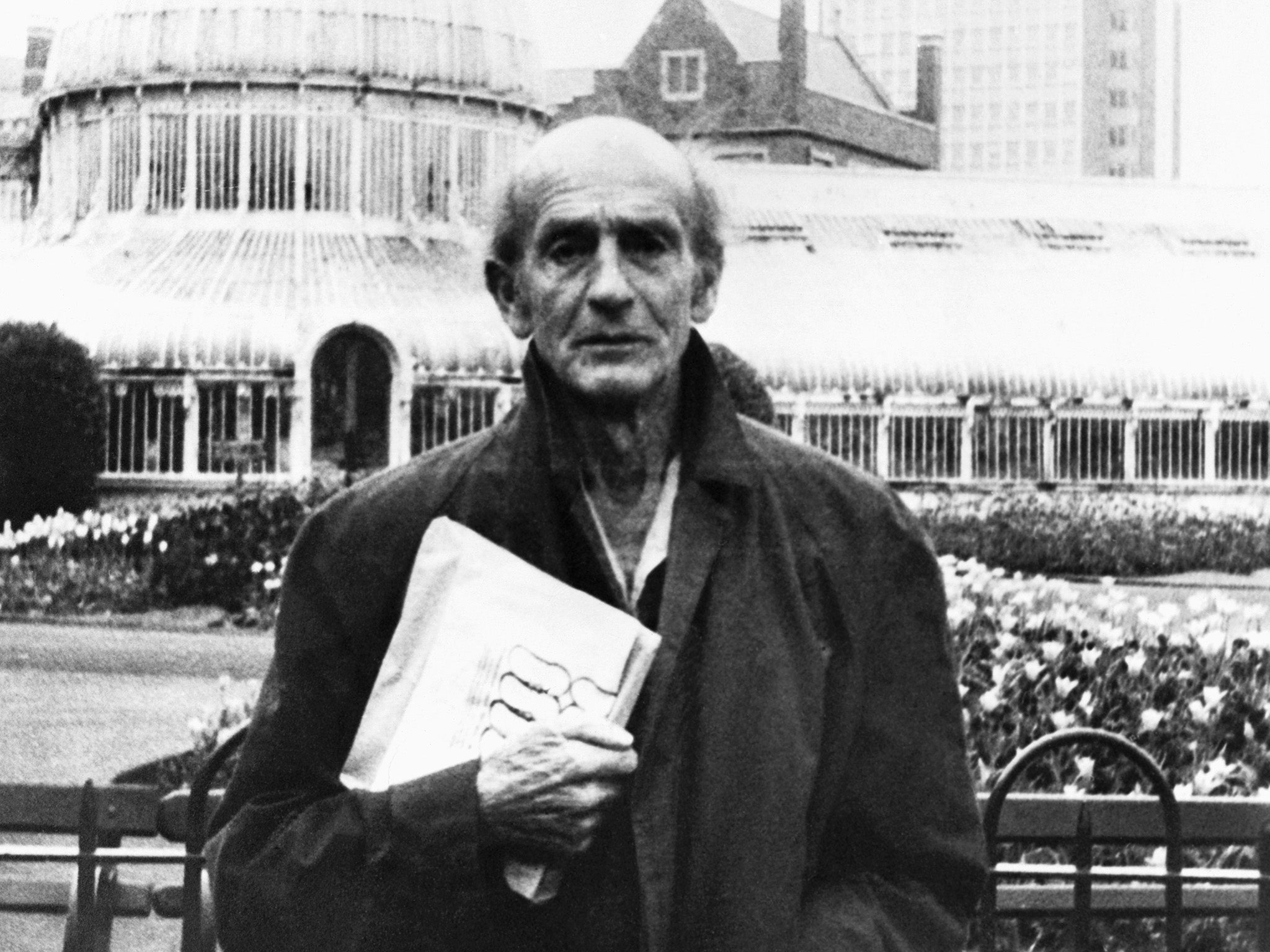

It may seem strange to choose an anthology of mainly British literature beginning with Chaucer’s Parlement of Foules and ending with HG Wells’s The History of Mr Polly as my book of a lifetime. But Hugh Kingsmill’s The High Hill of the Muses, posthumously published in 1955 (he had died six years earlier), became my guide to literature at the age of 20. What I absorbed then has influenced me for the rest of my life. I discovered Kingsmill’s fiction and non-fiction at the local public library which, since I did not go to a university, became my principal place of learning. What Dr Leavis was for many of my generation, Hugh Kingsmill was for me.

As a critic he was as severe as Leavis, but had a different philosophy that sought to distinguish between Will and Imagination. At first glance, this anthology does not appear original. The most-quoted writers are Shakespeare, Blake and Wordsworth; and the most translated passages come from the authorised version of the Bible, Rabelais’s Gargantua and Pantagruel and Cervantes’s Don Quixote. He selected favourite pages which “have survived the corroding or purifying effects of time”. But it is his 10,000-word introduction, succinct, humane, humorous, imaginative and based on a lifetime of reading that had – and still has – such a deep effect on me. I cannot read his page on Johnson without having to stop to collect myself.

Elsewhere he tells us that only when “the drain on our manpower in the Second World War made my services as a schoolmaster necessary, if not desirable” that he studied Chaucer thoroughly. It was one of his pupils who first took him through the “Nun’s Priest Tale” “with its clear distant little scenes like the backgrounds in early Flemish painters, and its subdued kindly humour which seems at the same time to reveal and excuse the weakness of men.” Reading the Border Ballads in his late teens, “it was less the human beings in them that stirred my imagination than the black night and brief gray day in which they moved, the bare moors and fierce or wailing wind and the endless sea beyond”. Later he grew more vulnerable to human passions expressed with truth and intensity; their necessity and danger: “The uprush of agony after the stupefaction of loss,” for example, in “Clerk Saunders”.

Tastes change with time. HG Wells, “the Janus-faced Little Man, who looked forward with a fixed glance at a world swept clean of everything which was hurting him in the present, also looked backwards in regret and humorous affection at all that had moved him in the past, the hopes and formless aspirations and comforting illusions of Mr Polly, and the ‘other dreams’ which are the theme of The Sea Lady and which, as the elder Ponderevo lies dying after the collapse of his worldly triumph, gleam fitfully in his fading consciousness”. This mingling of biography, landscape and literary criticism, of dreams and experience, was very appealing to me, and I have tried to follow it in my own work.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks