BFI Player: How a streaming underdog is finally coming of age in lockdown

In a sea of homogeneity, the British Film Institue’s answer to Netflix and Amazon Prime has carved out a niche as the streaming world’s most diverse and inclusive alternative, writes James Moore

A veritable deluge of money has poured into streaming. Every entertainment and tech giant in America seems to have jumped in, armed with billions of dollars in the hopes that they can either steal a slice of Netflix’s pie, grab a piece of a bigger one, or best of all both. A good chunk of it has been raised in debt, and it’s a racing certainty that there will be some very high-profile casualties down the line, which will create some very big headaches, and generate some very big payoffs to CEOs (because there are always big payoffs when CEOs mess up).

In the midst of such a feeding frenzy, you might think that a niche player run by a British cultural charity would be at grave risk of ending up looking like one of the victims in a J-horror movie. Not so, says the British Film Institute (BFI). We’re doing just fine with the BFI Player, thanks very much.

The “Player”, as those who work on it refer to it, is clearly a flyweight in financial terms. But the best flyweights are usually worth watching because they’re entertaining and they pack a punch. This one has been helped in no small part by wearing a strikingly different coloured pair of gloves, not only in terms of its consumer offer but also its business model.

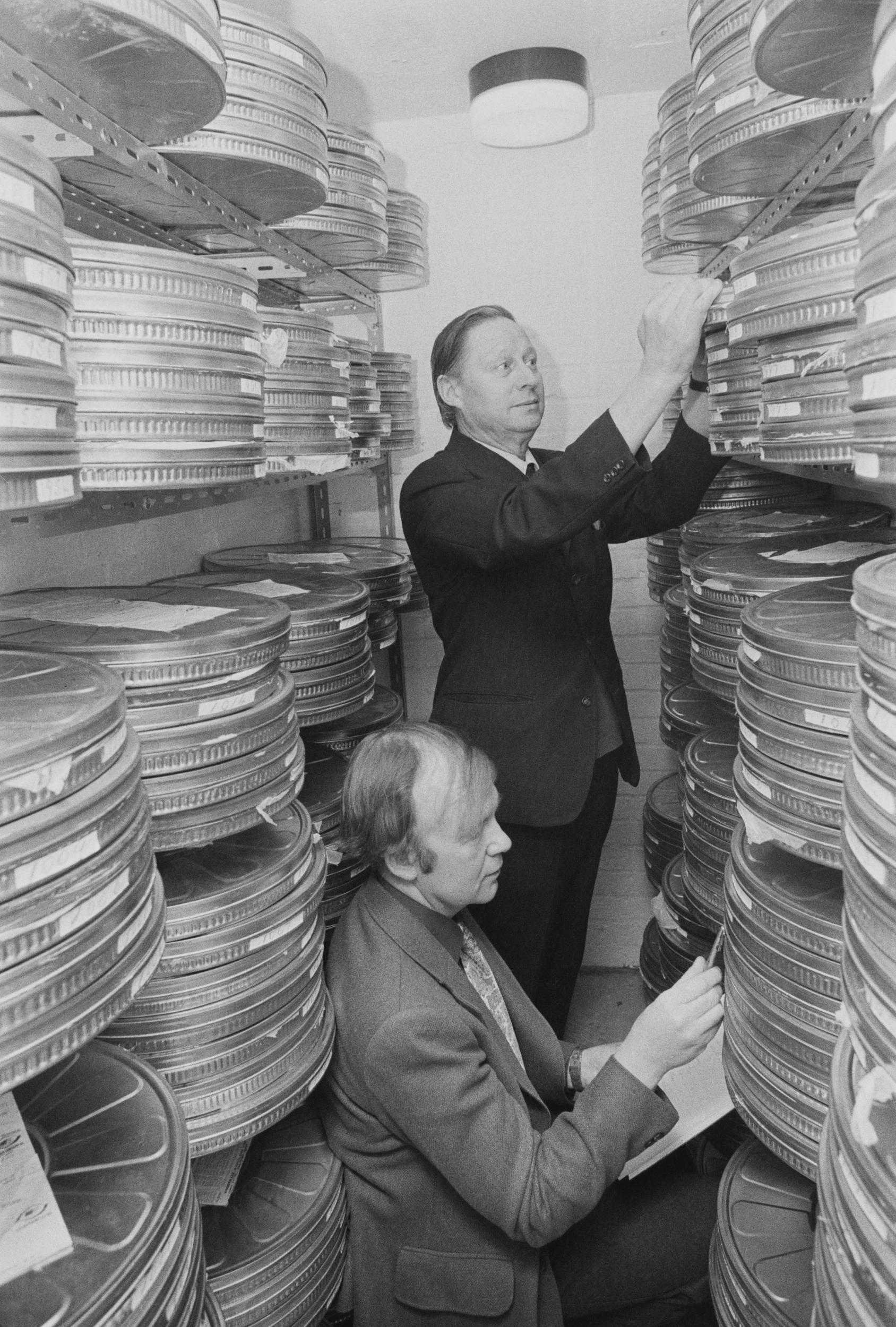

The latter is a hybrid. As well as the core subscription service there is a rental business, DVD sales and a digitised library of free content culled from its vast archive. Some of the digitised public information films, which can be found in the latter, are a hoot. Among their number is also the only surviving British picture dating back to the Spanish flu of 1918 and 1919, which is the last one to have a comparable impact to the Covid-19 crisis we are in the midst of.

In the silent, captioned film Professor Wise delivers his important lecture TO YOU (sic) on how to avoid joining the shudderingly high death toll. More people perished from the virulent H1N1 strain than lost their lives through the First World War.

The subscription-based part of the Player aims to offer an alternative to a sea of big company homogeneity. “I think people are looking for that,” says Heather Stewart, the BFI’s creative director of programme. The figures the BFI was willing to share with me bear that out. The organisation says that it has seen a 250 per cent rise in subscriptions and an even bigger increase in viewing figures (300 per cent) this year.

That isn’t surprising given that the pandemic closed cinemas and everywhere else for several months, starving people for things to do and drawing them online in search of entertainment options. But the BFI had reasons to feel concerned when it initially struck and most Britons were first confined to their homes.

Ed Humphrey, digital director, who boasts Disney on his CV, explains why: “There was an awful lot going on and we feared we might get lost what with the revivals, and the replaying of theatre performances on YouTube and all the streaming that was going on. So yes, we were a bit worried at first.

“But the way it’s turned out is that people are watching more films. Audiences have increased their viewership rate for us and that’s really really important given that what we are trying to do is build ourselves into their entertainment mix. We saw the steepest organic growth at the beginning of lockdown when it was at its most restrictive. As restrictions have lifted growth has gradually slowed.”

The player is very obviously pitched at cinephiles, those with a deep love of film and the desire to seek out offerings from beyond Hollywood and indeed the English language. It’s not where you’re going to find blockbusters because there are plenty of places doing that. Instead, it seeks to offer a window into the best of British and world cinema, cult movies, classics culled from the medium’s rich history, curated seasons, with a library of more than 500 films.

That might look like a relatively small number when compared to the vast stores boasted by some of the competition, but discovering what the latter has to offer isn’t always easy, which is why there are so many websites devoted to telling you about the hidden gems on, say, Netflix that you weren’t aware were available to you with your subs. The algorithms they use can be highly eccentric, regularly coughing up lists based on people’s previous viewing history that miss things they might like to see and include things that make them go “ugh”. Stewart thinks their service has the answer to that: the human touch via the aforementioned curation.

The appeal of the model is that it offers viewers more bang for their buck, a portal into new cinematic thrills they mightn’t have been aware of

This isn’t unique to the BFI Player. It’s a model that’s also been adopted by some of the other smaller players. Screen Anime, the ongoing online anime festival run by Anime Ltd that The Independent recently featured is another example. The appeal of the model is that it offers viewers more bang for their buck, a portal into new cinematic thrills they mightn’t have been aware of, put together not by a piece of computer code but by similarly enthusiastic and knowledgeable people.

Stewart cites events such as the Japan 2020 festival, featuring around 100 titles from that nation’s expansive cinematic tradition, including acknowledged classics such as Seven Samurai and Tokyo Story together with many more obscure, cult offerings from multiple genres. “When we bring these forward you can feel confident that this is a very comprehensive rounded and deep take on a country’s history and present put together by cinephiles,” Humphrey says.

“Post (Bong Joon-ho’s South Korean Oscar-winning) Parasite, there are a lot more people willing to clear what he called the one inch-tall barrier and watch subtitled content. It’s only cultural organisations that can do seasons like this. There is a huge wealth of research and curatorial expertise that’s gone into it. That season was in the works for many years. It’s part of our ambition to make films that might seem alien and foreign familiar.”

Perhaps surprisingly, despite a relentless diet of grim news, there wasn’t a notable increase in viewings of more escapist material during lockdown. But, he says, what they did find was “a wider number of titles were being watched as it continued – about 10 per cent more individual films from the catalogue were viewed in the month of May compared to pre-lockdown levels. This suggests that our existing audience are exploring deeper into the catalogue.”

“We had to make a very quick decision on the Japanese season,” says Stewart of the event, which was supposed to feature a series of screenings at the BFI Southbank and nationwide from May through to December in addition to online content via subscription. “We decided to put it all on the Player. There’s all this great stuff. J-horror, anime, samurai movies. What we didn’t know is whether audiences would follow us, but they have. It’s picked up 50,000 views so it’s been very popular.”

While the inability to see some of these films on the large screen will have disappointed people with tickets, with so many people at home, on furlough, looking for entertainment options, you could make a case that the move extended the season’s reach. It is now hoped, with the BFI Southbank announcing plans to reopen its doors again in September, to show some of them on the large screen in 2021.

But, given its growth, does the Player wash its face? Does it turn a profit? Humphrey is coy, merely saying that its subsidy has fallen every year since its launch in October 2013, sandwiched between Netflix and Amazon Prime, which is itself arguably subsidised by the tech giant’s vast array of highly profitable businesses. Stewart is quick to stress that’s not entirely the point. While the BFI needs to generate revenues and earn money on them, its goals are artistic as much as commercial, otherwise it mightn’t have been able to justify the costs of putting on such a large event as Japan 2020.

You could, however, make a case that it’s a little more sincere about what it’s doing than most. Its outreach efforts were under way before the killing of George Floyd in the US

It is set up as a charity with the specific purpose of offering the best of British and international cinema. Another part of its role is to support the independent sector. To this end, independent cinemas have been offered a landing page on the platform. “Their programmers can tailor it to their needs. A commercial platform wouldn’t have gone to that sort of trouble,” says Stewart.

Nonetheless, the BFI draws a significant amount of its funding from the taxpayer. That subsidy is the sort of thing that might ruffle the feathers of certain politicians, who might be inclined to see the service only in terms of cost and to miss out on the value part of the equation. Stewart and Humphrey are keen to counter that. They point to the importance of supporting independent British film and British filmmakers, and of providing a shop window for work which sometimes struggles to get into multiplexes.

Marc Jenkin’s award-winning Bait is one example. Where it was screened it proved capable of selling out theatres, especially in Cornwall where it was shot. Critically lauded, it has since generated 100,000 views on the Player. The eerie Little Joe, which feels like a John Wyndham novel thrown into the 21st century, is another.

Stewart stresses that that BFI generates a positive return for every £1 of subsidy. There’s also the “soft power” of cultural exports which shouldn’t be underestimated. But at the same time, she and Humphrey are keenly aware of the organisation’s need to reach out beyond what might be considered its traditional audience.

It’s attempting to do this with efforts to draw in minority audiences, such as Britain’s black and minority ethnic community. It’s now de rigueur for streaming platforms to have a Black Lives Matter section, and the BFI is no different.

You could, however, make a case that it’s a little more sincere about what it’s doing than most. Its outreach efforts were underway before the killing of George Floyd in the US started a much-needed conversation about racial justice and had the big streaming services falling over each other to jump on the bandwagon.

The week-long Who We Are series of online events and film programmes, designed to celebrate and spark debate around black British film, was programmed with the award-winning film exhibition company We Are Parable. It took over BFI channels for a week. There is also the popular Women Make Film series, and BFI Flare, the LGBT+ event, which, like Japan 2020, had to be rapidly migrated online at the start of lockdown.

Class is addressed through the Working Class Heroes section, spotlighting working-class actors in what remains a very middle-class, and above, industry that can be extraordinarily difficult for those not from a privileged background to enter, let alone thrive in. So maybe it’s not just the cinephiles’ streaming service. Maybe it’s also the inclusive streaming service? While it has a way to go, and some hires to make, perhaps it’s also the diverse streaming service.

As streaming operations go, the Player is a little bit different, partly through a desire to celebrate diversity. That makes the Player an even worthier part of the current streaming circus.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks