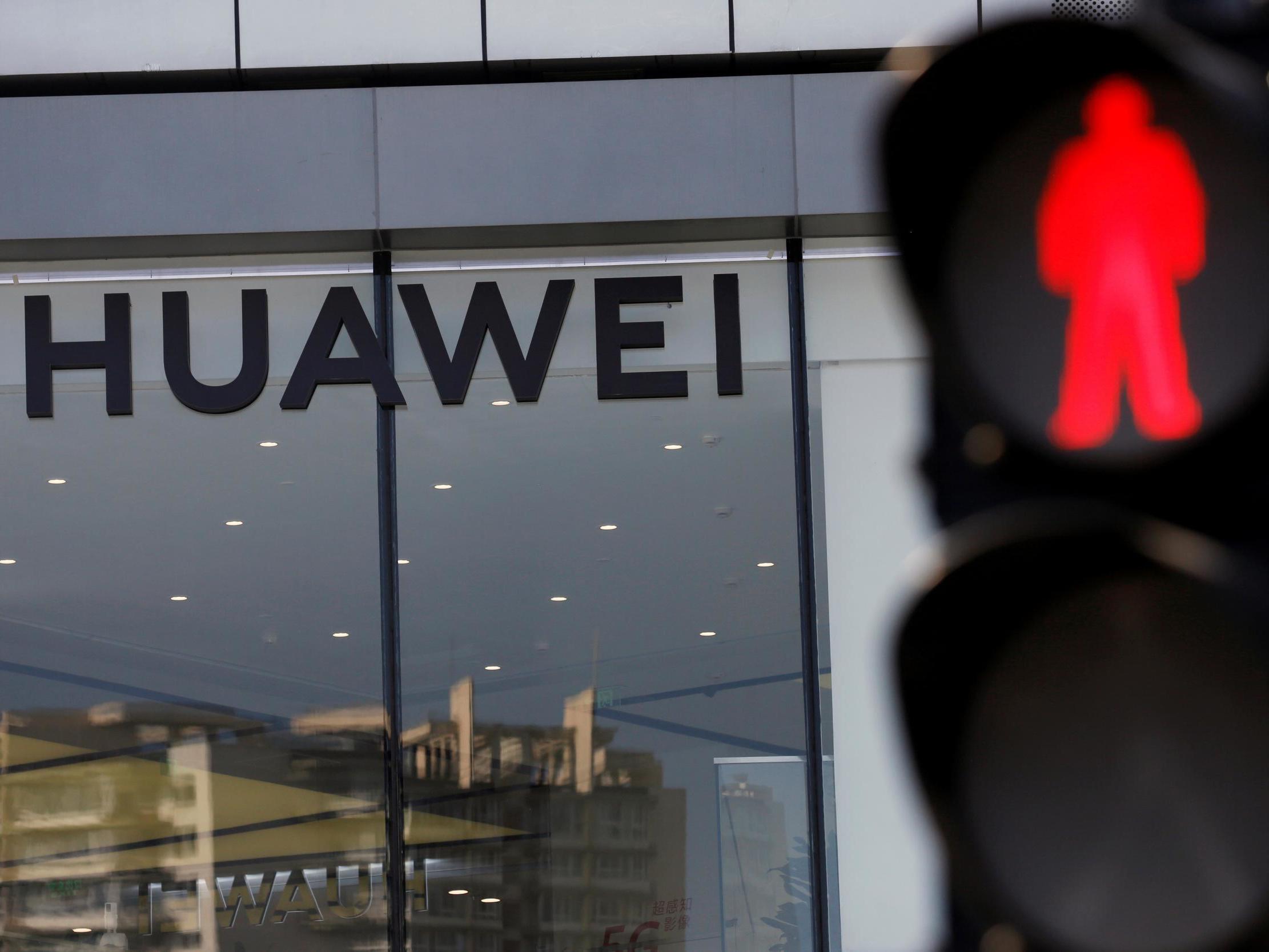

Huawei’s removal from Britain’s 5G network was all but inevitable

Analysis: US sanctions have tipped the balance against the Chinese firm, writes Kim Sengupta

The announcement that Huawei will be barred from Britain’s 5G network in a few years is hardly a surprise. That was the widely predicted outcome once an investigation was ordered into the effect of US sanctions on the Chinese telecommunications company.

Boris Johnson’s government had little choice but to end Huawei’s involvement after sustained opposition from allies, in particular the US, an international geopolitical reset over China following the coronavirus pandemic and a growing rebellion among Tory MPs.

But was this yet another volte-face that Boris Johnson’s government has become known for, using the sanctions report as an excuse? Or have the American measures made the presence of Huawei so risky that it simply had to go? And if there is now so much concern over national security, why is the company staying in the 5G network for another seven years and in the 3G and 4G ones even after that?

In January the British government decided that Huawei would be allowed into the 5G network, but with its involvement capped at 35 per cent. This was done despite warnings from the Trump administration that the move would put intelligence-sharing at jeopardy and the decision of a number of allies, including Australia, to ban the Chinese multinational from their infrastructure.

The pressure, however, continued to grow with some American politicians warning that ignoring Washington’s concern about security may pose problems for a trade deal between the two countries – one of the supposed rewards for Brexit. Meanwhile, there was rising antipathy towards the Chinese government among MPs and opinion formers, in this country as elsewhere, over claims that Beijing had deliberately hidden information about the early spread of coronavirus.

Then came Washington’s sanctions on the use of American components in Huawei equipment. An emergency review by the UK’s National Cyber Security Centre (NCSC) was ordered with alacrity by Downing Street, while briefings began to suggest that Boris Johnson wanted Huawei totally eliminated from the UK network by 2023 – a timescale viewed in industry and security circles as fanciful and put out mainly for PR reasons.

The NCSC concluded that the American measures have made Huawei unsafe. Ian Levy, its technical director, sought to explain: “The amended [US] rule says that no one, anywhere in the world, can send Huawei-designed chips to Huawei if US technology was used in the design tools or manufacture processes.

“This does not just mean that Huawei can’t use design tools that contain US technology. It also means no one else can take a Huawei design and turn it into chip manufacture instructions using tools that contain US technology.”

Countering this, says Mr Levy, would mean a company breaking US laws and manufacturing the chips anyway: Huawei switching chips which are not Huawei-designed with American components, or someone making new tools and design processes for chips without using American technology. These options are not feasible, he maintains, on legal, technical or security grounds.

A number of cyber analysts say, however, that Huawei is not being ditched for security reasons, as the government claims, but because American action has left the company unable to function as a reliable supplier.

James Sullivan, head of cyber research at the Royal United Services Institute, and Conrad Prince, a distinguished fellow at the think tank, wrote in a paper after Tuesday’s decision: “The single-minded US strategy of making Huawei effectively unviable may well mean that the company cannot be regarded as a sufficiently reliable supplier in the medium to long term.

“For the UK, this is about Huawei’s ability to supply verified components or conduct maintenance, rather than any dramatic new cyber security revelations. But the impact of sanctions aside, moving away from even the relatively small role envisioned for Huawei in the UK’s 5G network, this change in policy is unlikely to make the network materially more secure.

“The west’s dependence on China is clear; 5G is just one, relatively small, manifestation of this. If the UK’s new approach is to technologically decouple from China, it will need a serious and more coherent effort from western governments and industry to do so.”

A number of states, not just in the west but elsewhere are, in fact, looking at decoupling from China and considering the security aspect of Chinese investment in strategic industries, including healthcare, in the wake of coronavirus pandemic.

Measures have been taken by Canada, Australia, India, Spain and France. Margrethe Vestager, the EU completion policy chief, has suggested that member states should consider taking ownership stakes in companies threatened by takeovers, particularly by Chinese companies.

But the UK will have greater difficulty in this than many other countries because successive governments, that of David Cameron in particular, have assiduously tried to cultivate Chinese trade – a process which had become increasingly urgent in the uncertain economic landscape of Brexit.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks