Hong Kong lawyers fear China will target them for representing new national security cases: ‘Anyone could be at risk’

Loose definitions in new law mean activists fear speaking to foreign media and lawyers risk being accused of ‘subversion’ for defending national security suspects, Viola Gaskell reports

Hong Kong’s human rights lawyers fear they could be targeted by the Chinese state as they prepare to defend the first wave of people arrested under the city’s controversial new national security law.

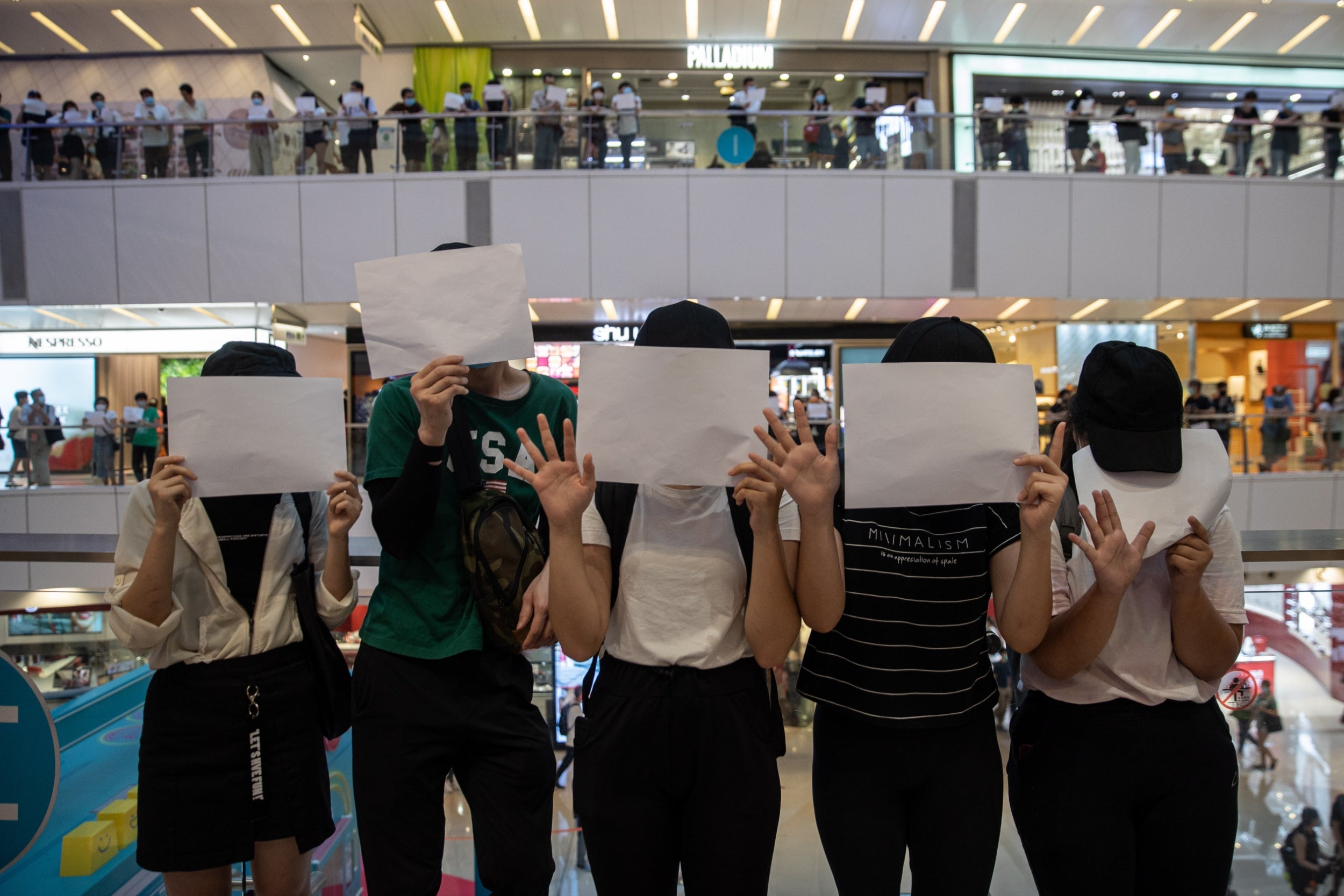

During last week’s 1 July protests, which began within hours of the law’s enactment, 10 Hong Kong residents between the ages of 15 and 67 were arrested on suspicion of “inciting or abetting others for the commission of secession or subversion”.

Those detained were apprehended for possessing stickers, pamphlets, and flags deemed as “subversive” or “secessionist”. One man was arrested for wearing a T-shirt bearing the slogan “Free Hong Kong”, according to his lawyer.

Under the law, which defines and bans the crimes of secession, subversion, terrorism, and collusion with foreign forces, offenders could be sentenced to life in prison or extradited to mainland China, where the death penalty is still widely used and conviction rates exceed 99 per cent.

Lawyer Janet Pang, who gave pro bono legal advice to multiple arrestees under the new law, told The Independent that the severity and vagueness of the legislation has her clients and their families “extremely worried”.

After protests erupted on 1 July, Pang followed those being arrested to the Ma On Shan police station, where suspected national security offenders are to be detained.

She said that though the bail process was fairly standard, both lawyers and the police appeared to be uncertain of how to proceed under the new law. One procedural difference that struck her and her team was that multiple arrestees had DNA samples taken at the station.

“This is not normal in Hong Kong unless it is deemed necessary for taking evidence, generally in cases of rape, grievous harm, or drug cases,” she said. “I do not see why it would be necessary when offence is the possession of stickers and pamphlets.”

China has for years been building the world’s largest DNA data bank as part of the country’s high-tech surveillance grid that police say is necessary to track criminals. Pre-existing Hong Kong law stipulates that the collection of DNA samples is reserved for serious cases.

The vagueness of the law has left some lawyers questioning their own impunity when representing defendants charged with breaching national security. Legal professionals who defend activists and journalists on the mainland have a history of imprisonment for charges like “subversion of state power” – a crime under the new Hong Kong law.

In 2015, more than 200 human rights lawyers and legal activists in mainland China were rounded up, detained and accused of defaming the Chinese Communist Party. Some were imprisoned for years without trial.

Despite increased risks under the new law, Pang and other lawyers who have represented protesters and journalists in the past year say they have no intention to stop.

A senior solicitor said that regardless of the law, the role of lawyers in Hong Kong remains “to fearlessly defend and protect the rights of our clients whoever they are and whatever they are accused of doing ”.

Lawyers for those arrested and bailed last week have advised them that it is too dangerous to speak to journalists about their situation. Pang, who is also a Civil Rights Observer, says that what was previously the benign act of speaking to a journalist, especially one from a foreign news organisation, now holds potential risk. “The law is vague [enough] that it seems we can easily fall into the trap of committing a crime”.

A barrister who represents protesters pro bono said that though “speaking the truth or giving out an opinion should not be regarded as collusion, when the authorities have the power to interpret the law – anything could fall into that category”.

“Anyone in Hong Kong could be at risk. If we will be at risk as well, does it mean that we should stop helping people? I don’t think so. Yes there is fear... but then what?” he said.

Under the Fugitive Offenders bill that was withdrawn last year after months of mass protests, extradition would have been at the discretion of Hong Kong’s judiciary. With the new law, national security agents appear to have the power to transport defendants to the mainland without the knowledge or permission of Hong Kong’s judiciary, according to a senior barrister.

Another senior solicitor, requesting anonymity, said the law’s broad and nebulous nature, combined with the possibility of extradition, was meant “to impose white terror”.

“There has been and there will continue to be a great deal of self-censorship and that is part of the absence of freedom of expression. When people don’t feel that they can speak freely, our freedoms have been lost – and that is what has happened.”

It is unclear whether most of those arrested under the new law will be charged, and to what degree. Nine have been released on bail and told they must report to police at the end of the month.

Only one of those arrested, Tong Ying-kit, has been charged under the new law for inciting others “with a view to committing secession or undermining national unification” and “terrorist activities”.

Videos show Tong riding a motorcycle trailing a flag that bears the now-banned slogan, “Liberate Hong Kong, Revolution of our Times”, when he is intercepted by police. Three officers were injured during the incident, according to police, while Tong was hospitalised with broken bones. He appeared in court on Monday in a wheelchair, and was denied bail while his case was adjourned until October.

Vee, who was arrested last year for illegal assembly, said the new possibility of being arrested for “simple acts of self expression” has heightened her fear of being detained again.

“We have a generation of people who have been traumatised and criminalised, and this law will only deepen the trauma,” she said.

“This is a new paradigm in Hong Kong,” said the senior solicitor. “People will be watching to see what happens to those arrested on 1 July. It will be a bellwether as to what the authorities will do and how fast they are going to be doing it.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks