Alexander Fury: The meaning of commercial in the fashion industry

Bestsellers don't have to play it safe, says our fashion editor

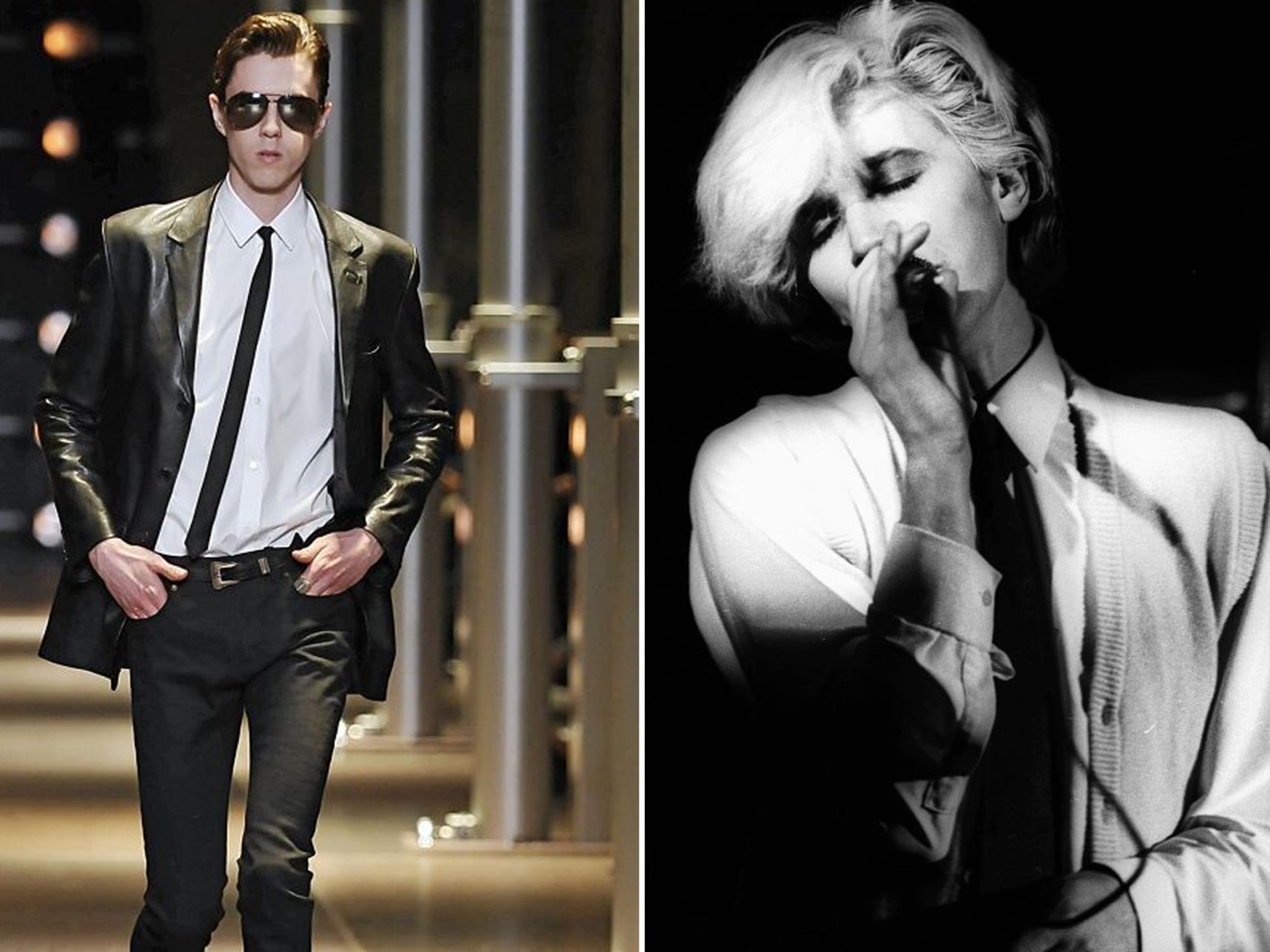

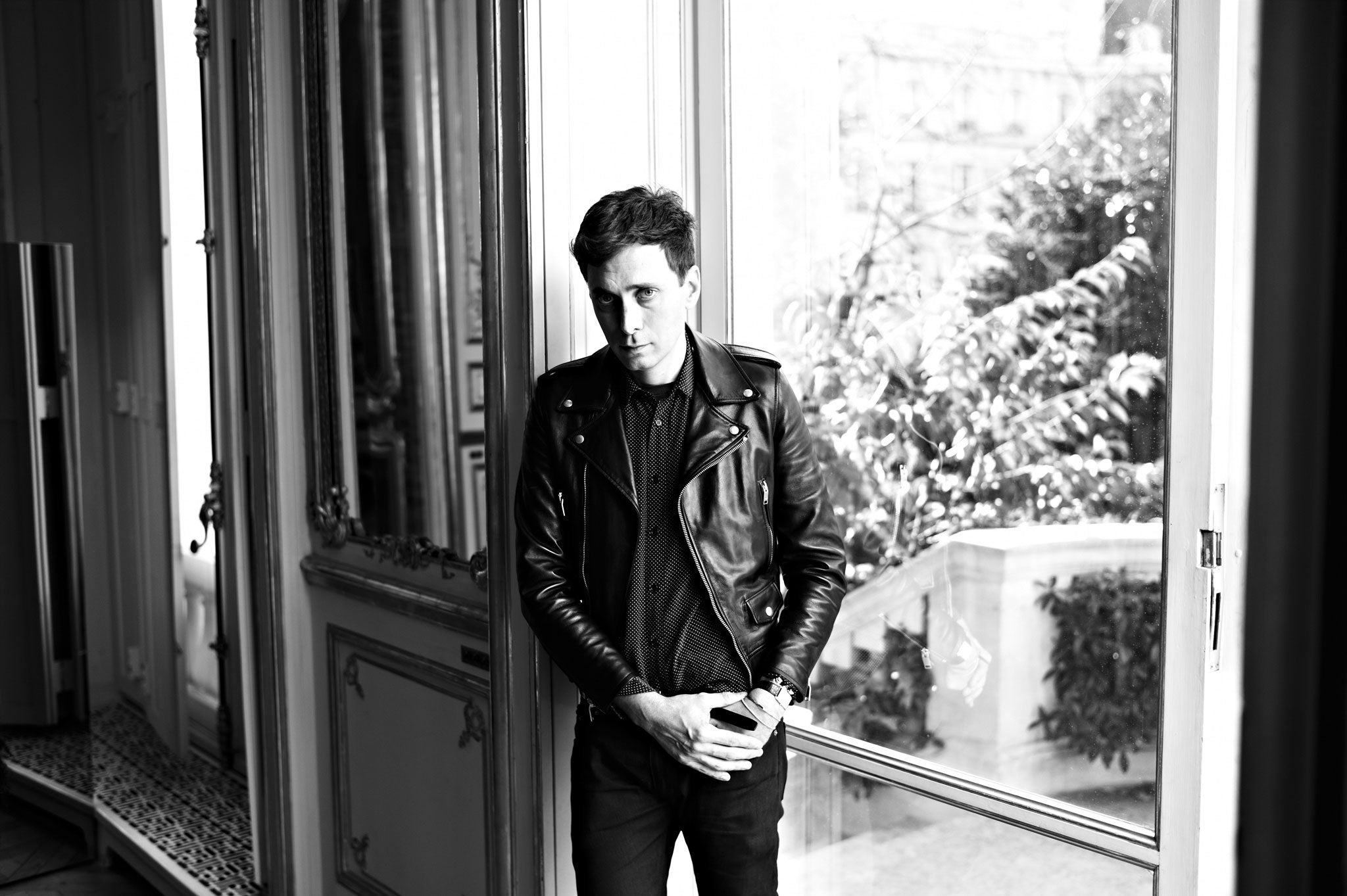

What does commercial actually mean when it comes to fashion? Well, it depends – as with so much else – on the context. Commercial is one of those words that can be positive or pejorative, can be hurled as an insult or heaped as praise. Example? Hedi Slimane's Saint Laurent, which was responsible almost solely for a 7 per cent rise in the Kering group's profits over the first half of 2014.

Regardless of the views of critics, such as myself, over the relevance, interest and overall fashion validity of the garments Slimane is creating at the label, the stuff is nevertheless shifting. Profits over the past six months jumped 26 per cent, backed by retailers, who invariably cite the label as a bestseller.

So, Saint Laurent sells. But does that mean it's worth buying? It's a question I often tend to ask about labels lauded for their commercial appeal. Not to sound like a gloom-monger, but shouldn't fashion be pushing us forward into something brave and even slightly uncomfortable? I mean psychologically, rather than physically.

Of course, that is a little at odds with the commercial. That's why, so often, designers cleave their "selling" and "catwalk" collections into two distinct halves. You may go for something so wishy-washy it barely has a flavour of the catwalk trendsetter, or opt for the designer's unsullied vision, straight-up.

But shouldn't that potent vision be what we want to buy into, if we can? Commercial is used far too often as a synonym for "safe" or "staid". Maybe desirable is the word we should be using: namely, the sort of desire that means you simply have to acquire something, regardless of the price. That would free designers up to do what they should do best: design really great clothes that we can hanker after and dream about.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments