On the hunt for the best bolognese recipe of them all

Leslie Brenner wanted the ultimate bolognese. Two months of researching, cooking and testing, and six recipes later, she just might have found it

Last year, my seasonal craving for ragu bolognese – the famous long-simmered meat sauce from Italy’s Emilia-Romagna region – failed to move on once the weather warmed up. Instead, it mushroomed into an obsession.

You could blame the Great Confinement and an exaggerated need for comfort foods.

But I also blame Evan Funke, the chef renowned for his pasta. Three months before lockdown, my son and I spent a chilly Saturday tracking down ingredients for the bolognese in his cookbook American Sfoglino. First, we purchased a meat grinder, as required by the recipe. Then, we chased down unsliced mortadella, prosciutto and pancetta, along with strutto – pork fat. The next day we made the ragu – a process so involved we had to start in the morning for the sauce to be ready for dinner. We began by cutting beef chuck, pork shoulder and the cured meats into cubes, then muscling them through our dinky, hand-cranked grinder, followed by celery, carrots and onions.

Once we had everything chopped and ground and browned and simmering on the stove (for five to seven hours!) we rolled out and cut tagliatelle by hand – leaving the pasta machine in the cupboard, as Funke has evangelised.

Read more:

That night, we sat with friends around the table to enjoy what we had wrought. The ragu was so spectacularly delicious – and so rich, no one could entertain the idea of seconds.

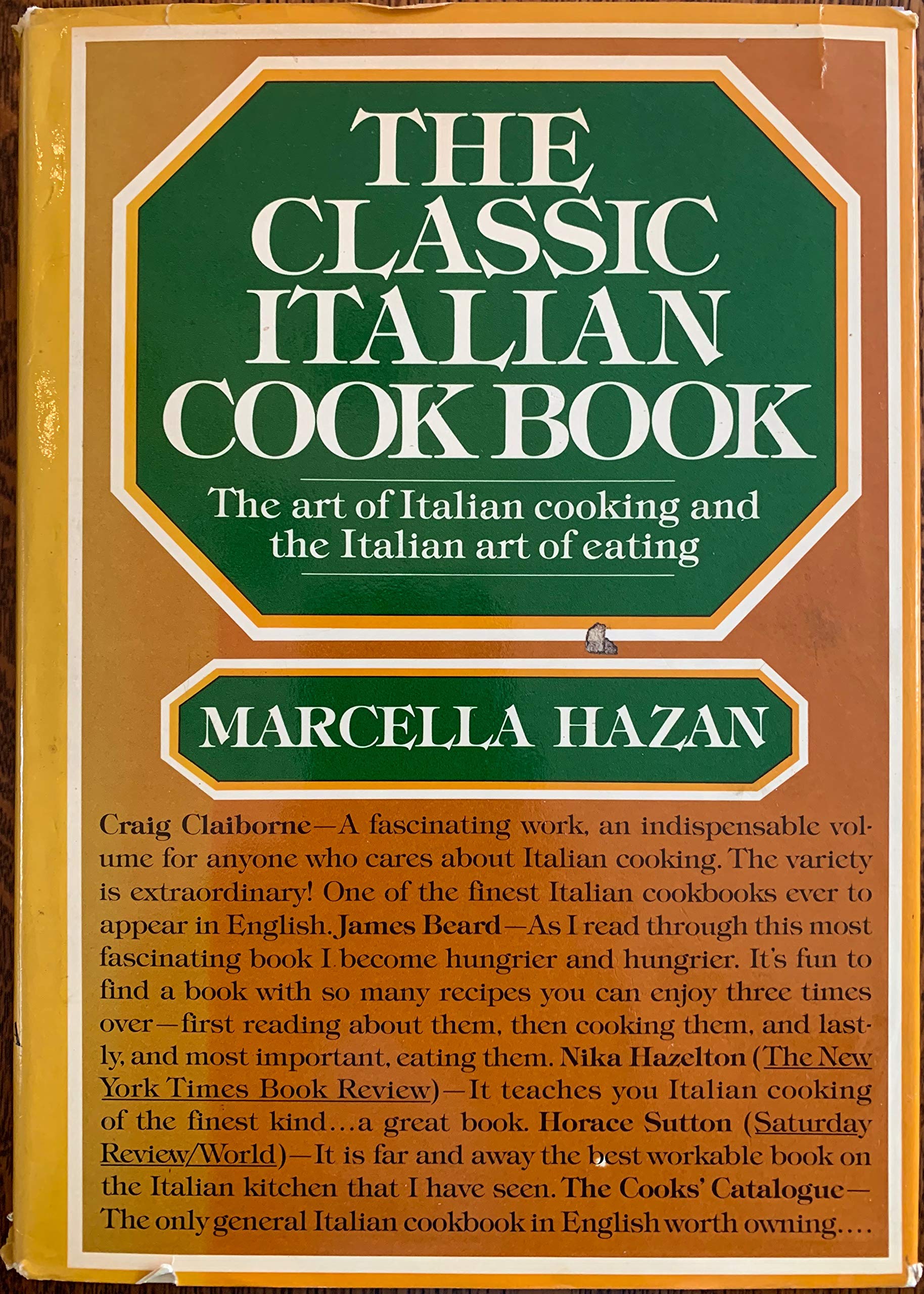

Before this extreme bolognese weekend, when the ragu craving struck, I’d usually improvise one, or turn to Marcella Hazan’s famous version from The Classic Italian Cookbook, or one of Lidia Bastianich’s three iterations in Lidia’s Mastering the Art of Italian Cuisine.

Now a burning (nay, simmering!) question gripped me: what is the very best bolognese recipe of them all? I would cook my way around in search of an answer.

What defines ragu bolognese? That depends on whether you rely on history (Pellegrino Artusi’s 1891 recipe), consult the Accademia Italiana della Cucina’s official 1982 recipe, or go by what Bologna’s famous cooking schools teach students – including Funke, who learned his ragu from Alessandra Spisni, founder of the cooking school La Vecchia Scuola Bolognese.

What the three definitions have in common is that ragu bolognese is a simmered sauce made with minced meat, plus carrots, onion and celery (collectively known as soffritto) browned in fat, and usually broth or stock. Tomatoes were not originally included. In terms of meats, Artusi called for veal and a little pancetta, while the Accademia calls for beef and pancetta. While Artusi did not specify a cooking time, very long simmering is a requirement: The Accademia called for two hours after the meat browns; many other recipes call for three hours or more.

These days, most respected versions call for beef mince and often pork, plus pancetta. All begin with some combination of olive oil, butter and/or pancetta or other pork fat. All call for soffritto and tomato, and two or three of the following: wine, stock and milk.

I zeroed in on recipes. Hazan’s and Funke’s had to be included. I’d also want to try the two traditional recipes in Bastianich’s book. Thomas McNaughton’s recipe seemed worth a try. And Domenica Marchetti’s recipe beckoned seductively.

Over two months, I cooked each, eating and assessing half on the evening it was cooked, and freezing the other half.

Straight from the stove, I loved them all. The two richest – Funke’s and Marchetti’s – made the strongest impression. Marchetti’s was sumptuous, with deep flavour achieved by super-slow, long browning of the meat. I tasted it just before adding the unusual finish – cream and julienned mortadella – and swooned. I liked the flourishes, but ultimately found them gratuitous. McNaughton’s, which hasn’t gotten much buzz in recipe circles, was a sleeper hit – not striking, but classic-tasting and very good. Of the two Bastianich entries, we all preferred the one with wine, which was profoundly flavourful but not overly rich.

Hazan’s was familiar and delicious to us all, but the top choice only for my son’s girlfriend. It was the only ragu with just beef, and no pork or stock. It was the sole recipe in which the soffritto wasn’t finely chopped, so the vegetables didn’t melt into the sauce as they did with the others. It was also strikingly tasted more of tomato and carrots, brighter in flavour, but less deep.

I considered my three favourites: Marchetti’s, Bastianich’s and McNaughton’s. I couldn’t single out one as best; there was something I’d tweak in each. So I stepped back, put my notes in a spreadsheet (to the amusement of my cellmates – ahem, family), and created my own recipe.

Here’s what I learned:

– Ragu bolognese is best eaten the day it is made. Despite what many Italian cookbook authors say, it loses vivacity in the freezer.

– White wine is a must. Its pleasant acid lifts the ragu’s flavour, while red wine’s tannins weigh it down.

– I prefer milk simmered into the sauce to cream added at the end.

–Tomatoes (crushed, milled or pureed) in the proportion of about 227g to 900g of minced meat, plus a little paste, for additional umami, are ideal.

– Long, slow browning adds valuable depth. I preferred Marchetti’s simple approach to Bastianich’s, which required close attention for 45 minutes.

– Butter tastes more at home than olive oil for starting the soffritto. Homemade beef broth (which Marchetti calls for) makes excellent ragu, but I didn’t find enough difference between it and good-quality purchased chicken stock.

– A couple non-universal touches add something worthwhile: garlic (which I found only in the Bastianich recipe, and which would no doubt be ridiculed in Bologna), and nutmeg.

Expecting a revolt when I told my family another ragu would soon come their way, I got cheers.

Lips smacking, forks twirling, grated parmesan fluttering, they gave the new recipe their unanimous approval.

Classic ragu bolognese

Active time: 2 hours | Total time: 5 hours

8 to 12 servings

Inspired and informed by outstanding recipes by Lidia Bastianich, Domenica Marchetti and Thomas McNaughton, this is Leslie Brenner’s (who is the editor in chief of Cooks Without Borders) favourite way to make ragu alla bolognese.

Legions of nonnas and authors have opined that the essential element for Bologna’s signature sauce is time. This recipe takes about 4½ hours to cook – and that’s once you have everything prepped.

It’s important to finely chop the onion, carrot and celery for the soffritto. The diminutive size, aided by the long, slow cooking, will allow the vegetables to melt into the ragu. Equally important are the minced beef and pork, which should be the best quality you can get, and are browned together slowly for about an hour. A pot wide enough to have plenty of surface area for the slow browning is essential to success.

If you’re using the ragu to dress tagliatelle or other pasta, when the ragu is finished and you’re ready to serve, transfer the amount of sauce you need to a large saute pan, keeping it warm while the pasta cooks. When the pasta is nearly done, spoon a little of the pasta cooking water into the ragu and stir it in, then use tongs to transfer the tagliatelle into the sauce, toss gently and cook for another minute before serving.

Storage notes: Leftovers can be refrigerated for up to three days or frozen for up to two months.

Ingredients

113g pancetta, cut into 1¼cm cubes

3 large garlic cloves

6tbsp unsalted butter, divided

1 medium yellow onion, very finely chopped (see headnote)

1 medium carrot, very finely chopped (see headnote)

1 large or 2 smaller celery stalks with tender leaves, if any, very finely chopped

450g beef mince (20 per cent fat, ideally grass-fed)

450g pork mince (ideally pasture-raised)

700ml good quality shop-bought chicken broth or homemade beef stock

235ml dry white wine, such as pinot grigio

1tsp salt

1 pinch grated nutmeg

235ml whole milk

2tbsp tomato paste

225g tomato puree or tinned tomatoes and juices, passed through a food mill or pureed in a food processor or blender

Freshly ground black pepper

Freshly grated parmigiano-reggiano cheese, for serving (optional)

Method

In a mini food processor, combine the pancetta and garlic, pulse a few times to break up the pieces, then process until it becomes a smooth paste.

Scrape the paste into a large, wide casserole dish or other heavy-bottomed pot, along with two tablespoons of the butter. Melt them together over medium heat, spreading the paste around with a wooden spoon. Cook until the fat is mostly rendered, about four minutes, stirring occasionally. Add the onion, carrot and celery – the soffritto – and cook slowly over medium-low heat, stirring frequently enough so the soffritto doesn’t brown – until the onion is soft, translucent and pale gold, which takes about 15 minutes.

Add the minced beef and pork to the pot, increase the heat to medium, and break up the meat with a wooden spoon as much as possible. Once the meat starts to faintly sizzle, reduce the heat to medium-low. Let the meat brown slowly, stirring occasionally and continuing to break up any remaining clumps, for about one hour, until evenly browned and burnished.

When the meat is nearly done browning, in a medium saucepan over high heat, heat the broth until simmering; cover and keep hot over low heat until ready to use.

Read more:

Increase the heat under the browned meat to medium-high and stir in the wine, scraping up any browned bits or deposits on the bottom of the pan. Cook and stir until the wine is mostly soaked in and evaporated, about three minutes. Stir in the salt and nutmeg, reduce the heat to medium-low and add the milk, cooking and stirring until it is barely visible, for about three minutes.

Measure 470ml of the hot broth and dissolve the tomato paste in it. Stir the broth with paste into the meat sauce, then stir in the tomato puree (keep the unused broth handy in the pot in case you need to reheat it and add more to the sauce later). Partially cover the pot and let the sauce simmer slowly and gently, stirring occasionally, until it is thick and all the components begin to melt together, for about two hours.

Stir the sauce – if it is starting to look at all dry, reheat the remaining chicken broth, ladle in a little more, about 120ml, and stir. Continue to simmer gently, uncovered, stirring occasionally and adding a little more hot broth or water as needed, until the vegetables have completely melted into the sauce, for about one hour.

Cut the remaining four tablespoons of butter into a few pieces and stir them into the sauce; add about 20 grinds of freshly ground black pepper and stir that in, too. Taste, and season with more salt and/or pepper, if desired.

Nutrition (based on 12 servings) | Calories: 336; total fat: 25g; saturated fat: 11g; cholesterol: 77mg; sodium: 593mg; carbohydrates: 8g; dietary fibre: 1g; sugar: 4g; protein: 16g.

© Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks