Farming confessional: We need to evolve so that we do not kill to eat

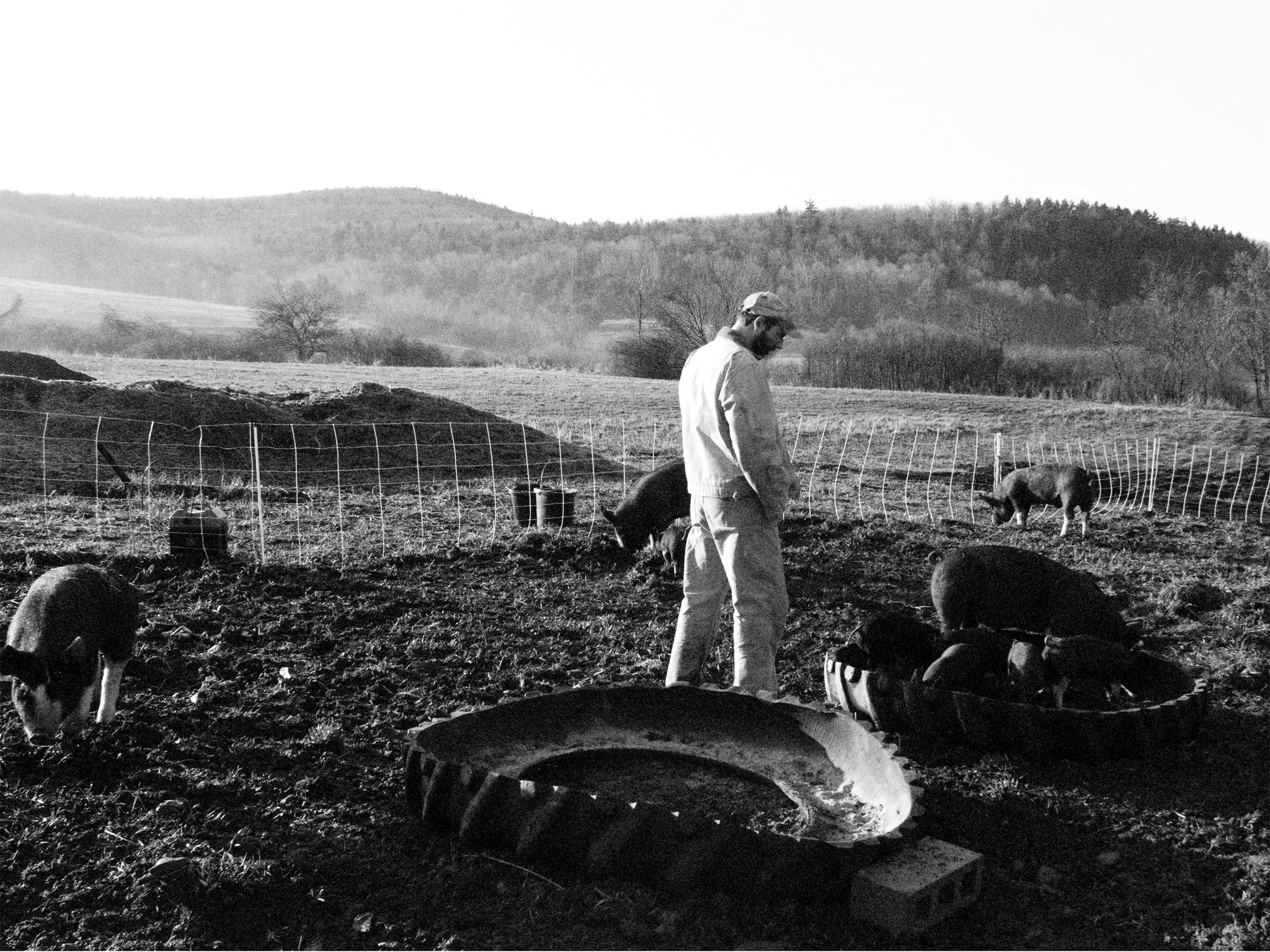

Bob Comis raises 500 pigs a year, aspiring to the highest possible welfare standards. But he is conflicted about killing animals for a living

In a recent blog post called "It might be wrong to eat meat", Bob Comis summarised his ethical dilemma in a sentence: "This morning, as I look out the window at a pasture quickly growing full of frolicking lambs, I am feeling very much that it might be wrong to eat meat, and that I might indeed be a very bad person for killing animals for a living." Here, he talks about the self-doubt he feels while raising animals for slaughter and his desire to see humanity evolve into a species that does not kill to eat...

I have no farming background. I was born and raised in the suburbs, and I spent more time in a shopping mall playing video games and eating fast food than I did outside. "Animals" meant cats and dogs. Of course, I knew the McDonald's hamburger I ate came from a cow, but that cow had no real existence for me. It wasn't until I started farming that livestock animals became real and individuated. And that's when my ethical struggle began.

I pursued a PhD in political philosophy for a number of years. I focused on postmodernist and poststructuralist philosophies, and this and identity, power and symbolisation are very much at the root of my ethical crises.

Watching the pigs shows me over and over again, in countless and sometimes very subtle ways, that there is much more to the life experiences of animals than most of us know or are willing to believe.

One morning, I woke up absolutely certain that killing animals to eat their meat was wrong. So it might seem as though I've sided with animal-rights advocates, but the long view that I'm taking on this makes my position more complicated than that. My feelings about the ethics of livestock farming ebb and flow. I have no plans to stop eating meat or raising animals for slaughter. But I believe that we as a species need to evolve into the sorts of beings that do not kill to eat. For now, I justify non-industrial farming as a necessary compromise that will gradually shift how we think about using animals as food.

Anyone who looks backwards for guidance on humane livestock farming is looking into an imaginary past. The concept of animal welfare would've been completely foreign to all but a tiny percentage of yesterday's farmers. I look to the past for practical day-to-day techniques, and to the future for guidance on how to treat the animals currently in our care.

By raising animals the way I do at Stony Brook Farm, I offer a way out of the industrial farming system, which is worse by orders of magnitude than the way I farm and should be abandoned immediately. That's how I rationalise my farming. I know that on the macro level, my small farm here in Schoharie, New York, does not change much. But on the micro level, I do make a difference in the lives – and deaths – of individual pigs.

I rationalise those deaths. The animals that remain behind clearly don't miss the ones I take to slaughter. There is no personal or community angst about the pigs that disappear. For me, this lack of reverence for the departed is permissive. But that's generally speaking. Recently I saw a pig in extreme distress as I left the paddock with a trailer full of others. I believed she was running back and forth along the fence line, frantic and anxious, making "Here I am, where are you?" vocalisations because I had taken her best friend.

When I take a large group of pigs to the slaughterhouse and leave only two behind, pretty consistently, those two pigs seem to be depressed for the next day or two. They spend a lot of time in their shelter, only coming out occasionally to eat and drink. After a couple of days, their normal routines and behaviours return. But, I believe the loss of a catastrophic percentage of their herd causes them psychological suffering, at least for a period of time.

My relationship to these observations and rationalisations has always swung, like a pendulum, sometimes acutely, sometimes gradually. Some of the things I do and see make me doubt, some make me confident.

When I first started farming, I used to stress the pigs out because I didn't understand them. It would get ugly when I tried to force them from one spot to another. After going through a lot of guilt over my own behaviour, I learnt that you can't force a pig to do anything, not without committing either psychological or physical harm. You encourage them to want to do what you want them to do and then you wait and let it happen on the pigs' schedule.

When the trip to the slaughterhouse isn't too long and there's bedding in the trailer, it's not stressful for the animals. Well-managed local slaughterhouses are essential to any livestock farming system that provides a high level of animal welfare. It all comes down to scale. Despite efforts, you cannot have a humane industrial slaughterhouse.

But no matter how well it's done, I can't help but question the killing itself. In a well-managed, small-scale slaughterhouse, a pig is more or less casually standing there one second and the next second it's unconscious on the ground, and a few seconds after that it's dead. As far as I can tell – and I've seen dozens of pigs killed properly – the pig has no experience of its own death. But I experience the full brunt of that death.

It's not the sight of blood that troubles me, but the violence of the death throes. Livestock science would assure us that these convulsions are a sign of the pigs' insensibility, but, as a witness, it is almost impossible to believe that the pigs are not thrashing around because they are in pain. And then that sudden lifelessness of the body as it is mechanically hoisted into the air, shackled by a single hind leg. I don't think anything could be done to make the deaths of the pigs weigh less heavily on me. I think a lot of animal farmers have the same ethical struggles as me, although I'm not sure how many struggle as intensely as I do. I believe this is likely the case with even non-corporate factory farmers. Feeling nothing strikes me as mildly sociopathic.

In some ways, hunting can be more ethical than even the best livestock farming. Hunters never pretend to be anything but predators. And when they're highly competent and refuse to take anything less than the cleanest possible shot, they don't cause animals any more suffering than I do.

In a way, livestock farmers lie to their animals. We're kind to them and take good care of them for months, even years. They grow comfortable with our presence and even begin to like us. But, in the end, we take advantage of the animals, using their trust to dupe them into being led to their own deaths.

I tried going vegan, but I don't have the cultural frame of reference for it. Every meal in my head includes meat as the centrepiece. No matter how many vegan cookbooks I read, I just couldn't envision vegan meals. Even when I followed recipes for entire vegan meals, I felt unsatisfied. It wasn't a lack of nutritional understanding. I couldn't reside, imaginatively, in a vegan world. The evening I fell off the vegan wagon, my wife and I went to our favourite burger place and my first bite into the burger was like coming home.

Even if I did stop eating meat, I would still farm animals. On any given day, I see 250 pigs on the farm that are perfectly content – as far as I can tell. The day they die is stressful for them, but the time between loading them on the trailer to the time they're killed is very short. And they're killed painlessly and without any awareness of it at all – as far as I can tell. When I see a pig casually bask in the sun and let out a big, satisfied yawn, or a pig jump up and run and twirl and play, I feel pretty confident that what I'm doing is OK.

We need farming with a high quality of animal welfare as a counterpoint to industrial, factory-style farming. There are real, working alternatives to the abolition of livestock farming. We need non-industrial farming to be as popular and widespread as possible, to be a point of contact through which people will have their dominant cultural identities disturbed. It is one of the first steps in our cultural evolution. Conscientious animal farming is necessary for a transition towards a vegan world. µ

This article first appeared in 'Modern Farmer'. The magazine's fourth print quarterly will be out on March 11; modfarmer.com.

Main image: Zach Phillips

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies