Freddie Bitsoie: The Navajo chef showing the world that Native American cuisine is far from boring

Freddie Bitsoie never expected his anthropology degree to lay the foundations for a career in Native American cuisine. Now, as his new book brings it to a wider audience than ever before, he’s not looking back

Freddie Bitsoie didn’t imagine a career in food when he was younger, although in retrospect it was always an underlying theme of his work, he tells The Independent. In fact, it wasn’t until an impromptu conversation with his anthropology professor at the University of Albuquerque that he ever really considered it.

He had been studying ancient food systems in Chaco Canyon, New Mexico. Archaeologists had discovered the remains of macaw feathers and cacao beans in the area, suggesting that ancient Puebloans, the largest group of people to live there 900 years ago, had tremendous road and trade systems between central America and what is now modern day Phoenix. “It was really fascinating to me that we tend to think about Native culture as people who generally stay in one area and just pick berries and eat them, instead of having a systematic way of wanting to have those things that they don’t have access to,” he explains.

Many years later, and he’s due to appear at next month’s Santa Fe Literary Festival, not far from Chaco Canyon, to share his culinary insights into Native American cooking and the rich Indigenous heritage of American cuisine.

To his professor, the jump into food seemed obvious. “Every paper that you’re writing deals with food, whether it’s storage, transport or preparation. If we combined all your papers together, you pretty much have a thesis for a book. So why don’t you go and study modern day cuisine and then relate that to prehistoric and historic cultures to see if there really was a food culture,” he said to Bitsoie, who thought: “Yeah… I like this idea!”

So he jumped ship… to Scottsdale, Arizona, where he enrolled at Le Cordon Bleu College of Culinary Arts. He got a placement at a Marriott Hotel (“The best $8 an hour I’ve ever made in my life”) and fell so in love with working in kitchens that he didn’t go back to finish his anthropology degree. That’s not to say it didn’t stay at the back of his mind, though. “All that time I went to college seemed to be a waste if I didn’t try to take advantage of it.” He saw a poster at the Heard Museum in Phoenix, the largest Native American museum in Arizona, advertising (what they described as) “Native American cuisine”. “The anthropologist in me just kind of clicked on,” he says. “I broke down the semantics of the term ‘Native American cuisine’. It just didn’t make any sense to me because there are over 570 tribes in the US alone, and there’s more in Canada. There’s just as many tribes in Alaska. They’re only talking about the lower 48.”

It made him think of his grandmother, who grew up on the border between southern Utah and northern Arizona. The Navajo food she cooks and eats would be completely unfamiliar to Native people from the Pacific Northwest, for example, nor would she recognise the tribal food from, say, northeastern Florida. “So, I thought: OK, there’s no way that we can possibly group everyone into this term ‘Native American cuisine’, because it’s just going to misrepresent how we feel as individuals in our own individual respective cultures,” says Bitsoie.

The environment plays an equally important role in shaping Native cuisine, he says. “Salmon is probably the best example because you can get salmon from the tip of the Alaskan islands and southern Alaska, all the way down to northern California. They’re pretty much the same species, but the food that they eat in every area is different, the water temperature is different, so the flavour is different.” Bitsoie has seen it prepared one way on North Vancouver Island by the Kwakiutl tribe – butterflied, in a woven cedar bracket and placed in butter – and another way further south, where they cut the salmon into fillets and cook them individually over a fire.

This difference in flavour can even be tasted in the plants that grow across different regions of the country. “I always like to use the French word terroir,” he says, which is more commonly used to refer to wine and how different minerals in the ground affect the grapes and, in turn, the flavour. “The berries taste so different in Washington state as opposed to northern Oregon. It’s these flavours that generate the differences in how the tribes eat.”

Another great example is… sheep. Although there is some evidence of wild species of sheep originating in parts of North America, domesticated farm sheep didn’t appear in the Americas until they were brought over by the Spanish. The impact of that introduction has trickled down to the way different tribes approach the meat. “The Hopi tribe [from northeastern Arizona] use sheep at times, but for the Navajo, it’s like their staple protein, and then some other pueblos in western New Mexico also utilise it.” Most tribes make use of the whole animal, not only eating the meat but using the wool for weaving.

The professional cook was trying to think of a way to explain this to a mainstream western audience when one day after work he turned on the TV and came across Lidia’s Italy, a series in which Emmy Award-winning celebrity chef and author Lidia Bastianich travels across the country, learning about and cooking the dishes of each region. “She would highlight a region and then base [that episode’s] menu off that particular region,” Bitsoie explains. He was engrossed… and inspired. “I thought, I can do the same thing, but make it my own. That’s how I started to talk about Native cuisine.”

He has since spent a decade travelling across North America, cooking alongside other Native chefs, participating in their rituals and learning all about their techniques and sacred dishes. This led him to become executive chef at the Mitsitam Native Foods Cafe at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian in Washington DC in 2016, a post he held until it closed due to the pandemic in 2020. He built a menu around everything he had learnt on his travels, featuring Indigenous foods from across the western hemisphere. “There was this great dish with courgette, summer squash, corn and just a little onion to add a bit of flavour,” he recalls. “You let it cook it down until everything is completely wilted. One day there was a Native American lady from Mexico in the cafe, and she said, ‘You’re cooking this wrong. You’re cooking it like how we cook it at home.’ I go: ‘What are you talking about?’ She says: ‘The gringos don’t like this.’ If you have the vegetables as al dente, that’s French style. So those two small differences are huge cultural differences when it comes to food preparation.”

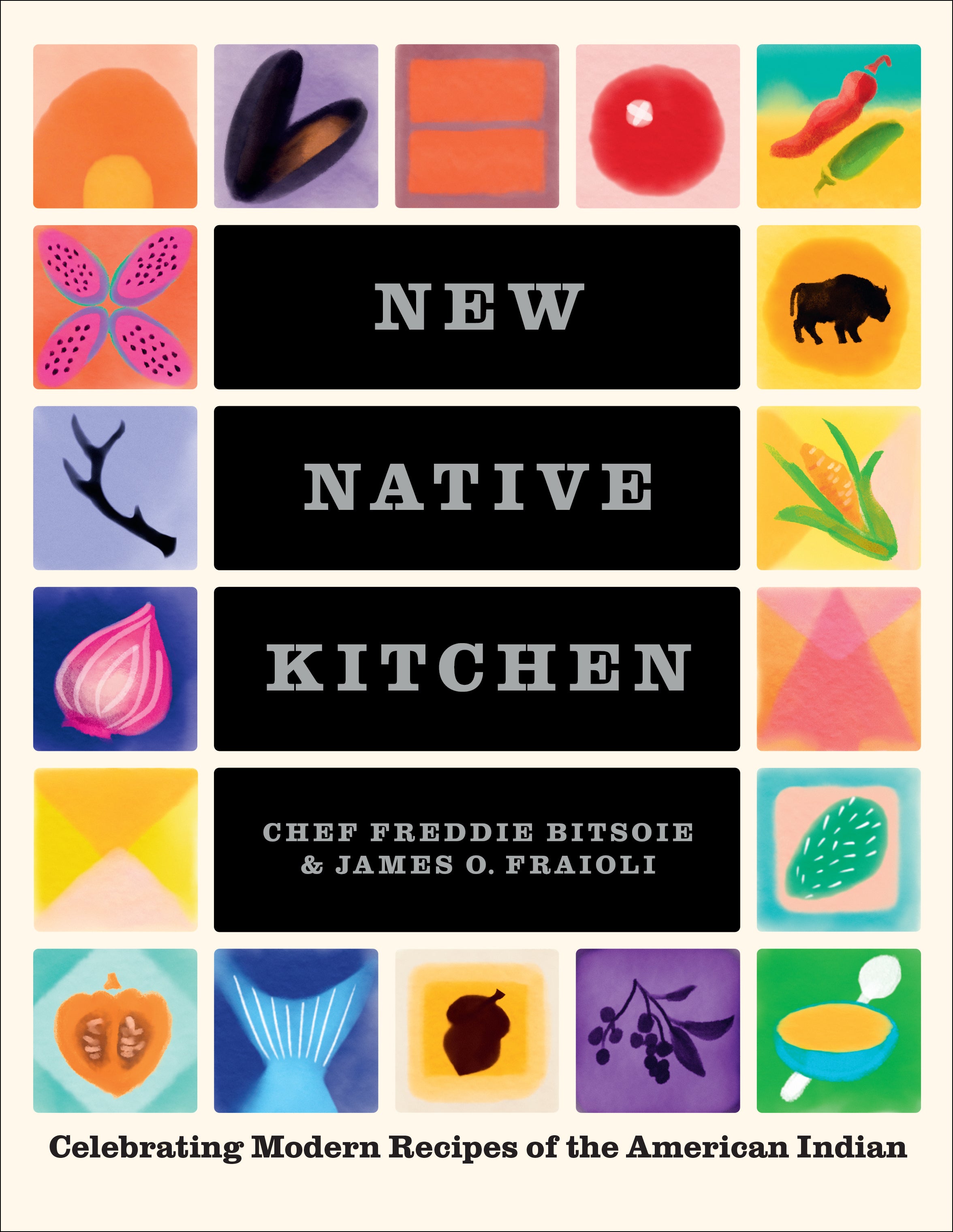

His new book, New Native Kitchen, was also born out of this journey, and reads much like a roadmap itself, but it’s called “new” for a reason, Bitsoie says. “It’s not called Traditional Native Cooking. It’s not called Grandma’s Cooking. It’s my experience of travelling throughout the country and Canada, and my knowledge of living in the southwest,” he explains. The book isn’t just “how I enjoy these foods as a professional cook, a Native American and a Navajo”, though, it’s “how we think the food culture should evolve”.

“Right now there’s a good chunk of Native chefs throughout the country who are focusing on the past, which is fine, because we need that knowledge,” he says. “We need instructors and cooks to present these foods in the way they were presented [back then]. And then we also have modern day cooks, who will fuse everything together. So we get foods from the southwest and we get food from the southeast and then they’re fused together, just like what we do with any type of cuisine globally.” Bitsoie has been playing around with recipes like this for the past decade, drawing on both his culinary education in predominantly French technique and his knowledge of Native American food.

There are a few things he won’t change, though. “In the book there’s hardly any frying because frying was introduced when the conquistadors came to central Mexico,” Bitsoie explains. “So those types of techniques are culturally different and the flavours are different, even though everybody loves fried food today.” Similarly, fat was always used as an ingredient but not in the same way it is today. “So, for example, they would use animal fat inside corn masa to make tamales, but it was never placed on a grill. Until Spanish arrival, cooking with dairy was the same thing. So these are things that are not in the book,” he says. In lieu of butter, Bitsoie uses coconut milk unless absolutely necessary. You won’t find any flour in the book, either.

While Bitsoie has certainly added his own spin to recipes inspired by the dishes he discovered on his travels, he believes “there’s no such thing as an original recipe”. One of his favourite dishes in the book, the chicken and tomato, is inspired by a dish his grandmother used to make at family gatherings. “They used to sear the chicken and then they take it out, put the onion and some peppers in, put the chicken back in with the stock and let it simmer before they throw the tomatoes in,” he recalls. “They’d put it on the table and everybody would eat it with a tortilla. I always thought this was the best thing ever.” But, when he became a chef, “I was looking at the recipe and I thought: that’s just a play on chicken cacciatore!”

Even now, he sees things through an anthropologist lense. “Some of my favourite terms are ‘infusion’ and ‘diffusion’, because those two have to exist in order for any culture to grow or evolve. Infusion means things that we bring into our own culture,” such as the sheep from Iberia. Bitsoie hopes the modernity of the book will bring Native cuisine to a wider audience that perhaps had never considered, or understood, it before.

“When I was starting out as a new cook, I helped out at this Native American event. This chef served what she called ‘the three mushes’: blue corn, steamed corn and sumac, which is all grinded down into a porridge,” Bitsoie tells me. “I was walking around the tables and all I could hear were non-Native people saying, ‘Native food is boring, bland and grainy’. That always stuck in the back of my head.” Well, with recipes like chocolate bison chilli, prickly pear sweet pork chops and sumac seared trout with onion and bacon sauce, and a passionate voice like Bitsoie’s at the helm, New Native Kitchen is sure to show the world that Native food is anything but boring.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks