Airscript: a theatrical Babelfish

When a musical is lost in translation or an aria is beyond your Italian, half the theatrical experience is lost. Now, thanks to the AirScript, you needn't lose the plot. Rhodri Marsden sings its praises

West End musicals aren't particularly renowned for their intricate plots and impenetrable dialogue; they're designed to be fun for all the family, with clapalong tunes, uplifting lyrics and – except for West Side Story – a happy ending.

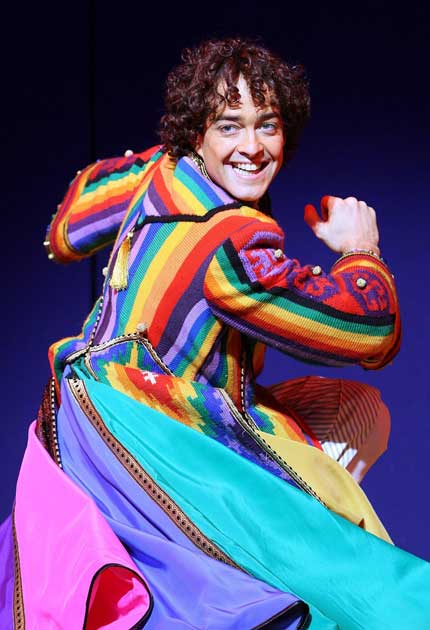

If your first language isn't English, however, a tale as straightforward as Joseph and his Technicolor Dreamcoat can feel as baffling as Ibsen's Peer Gynt. But a handheld device called the AirScript is set to change that, bringing live subtitles in a choice of eight different languages to the current production of Hairspray at London's Shaftesbury Theatre.

As Phil Jupitus, resplendent in an outsized housecoat and lipstick, delivers the line "some of your personal stains required pounding on a rock" to hoots of laughter (you had to be there), the text magically scrolls up the screen in Russian on the AirScript, which is about the size and shape of a satnav and is balanced on my knee. I don't speak Russian and can't vouch for its accuracy, but at first sight it appears to be a small step down the road towards the dismantling of those language barriers that can so hinder the average tourist. Well, at least for the duration of a musical.

The device is the brainchild of Alex Vegh, an Argentina-born translator (by day) and theatre enthusiast (by evening) whose venture neatly fuses his profession with his hobby. "It was an idea that kept coming back to me ever since I went on holiday with my family to New York when I was 12 and we went to see a production of Cats," he says. "My English was worse than it is now, and I remember thinking how great it would be to have subtitles in Spanish. But I certainly never expected to be the person who ended up providing the facility for people."

It's taken five years for the initial concept to get its first trial; a number of ill-forged business partnerships left Vegh floundering until Cambridge Consultants, a British technology company with an eye for innovative ideas, stepped in to assist. With investors on board and the product designed, all that was left was to persuade a theatre to try it – but that was easier said than done. "I never had a meeting with a theatre where they said they didn't like it," says Vegh, "but they're incredibly busy, and don't always have time to spend on something that they're not 100 per cent sure about." The Shaftesbury eventually took the plunge late last year, and now, as you enter the theatre, you'll see the AirScripts available for hire in the foyer at £6 a pop; tourists from Italy, Japan, Spain, France, Germany, China, and Russia can now delight in Scott Wittman's libretto.

Much of the concern from theatres centred around the idea that members of the audience would be moving a distracting screen backwards and forwards in the eyeline of the people they're sitting next to – like an auditorium full of people checking their mobiles for text messages. But the scrolling text of the AirScript is in a modest orange colour on a black background, and is even less distracting than someone peeking at their programme or chatting to a friend. This issue was just one of the problems faced by David Bradshaw at Cambridge Consultants during the product design phase. "It also had to be something that wasn't obtrusive for the theatres – there couldn't be any drilling or cables involved – but we quickly realised we'd have to design our own wireless protocol to allow a hundred or more wireless devices to be used in the same building at the same time. If you've ever tried getting online with your laptop at a conference, you'll know what I mean." And how is the scrolling text kept synchronised with the onstage dialogue? No particular magic there: Vegh's company, Show Translations, employ someone to sit backstage, triggering the lines via wi-fi as they're spoken by the actors.

A late addition to the AirScript's array of languages was English; theatres noted the device's potential appeal to the hard-of-hearing – something that hadn't occurred to Vegh. "We'd never even considered it, but now we offer free AirScript hire to those with hearing difficulties." This development has raised eyebrows at the British charity Stagetext, who have for many years provided open captioning where displays are situated on or next to the stage; they're involved in around 200 shows a year in around 50 venues across the UK. Their chief executive Tabitha Allum has given AirScript a cautious welcome.

She says: "Anything that makes the arts more accessible to deaf, deafened and hard-of-hearing people is great – especially as they can go to watch Hairspray whenever they want, without waiting for the theatre to book us to deliver an open captioned performance. But we've found that people who use our services do like open-captioned events on a social level. And the AirScript isn't always great for older people who may have difficulty quickly refocusing between the AirScript and the onstage action."

But it's Vegh's dream of a theatrical Babelfish that's generating the most interest. Enquiries have flooded in from Brazil, Germany, Canada – and, most notably, Mumbai, whose multilingual culture makes the AirScript a hugely attractive prospect. An updated version of the device, planned later this year, will start to incorporate some of the ideas that have occurred since its launch; from the mundane (such as access to programme notes) to the thrilling prospect of being able to order interval drinks without having to stand in a queue of 100 people. "We're very mindful that the AirScript will evolve," says David Bradshaw. "No-one really knows the market at the moment, but the device is built to adapt as the needs of theatres change." Of course, there'll always be the tricky problem of translating corny jokes into foreign languages – but at least we know that the technology is rock solid.

Futurism and tourism: Electronics for explorers

Google Street View

This extension of Google Maps and Google Earth that provides street-level panoramic views of major towns and cities worldwide has caused some disquiet since its launch in the UK in March 2009, being described as "an invasion of privacy" and "facilitating crime" – charges brushed off by the Information Commissioners Office last year. But for tourists planning a day taking in the sights of an unfamiliar area, it's becoming invaluable, and Google has recognised this by using a fleet of "Google Trikes" to add places inaccessible by road: The Eden Project, Stonehenge, Bamburgh Castle, Warwick Castle, the Lotus test track and the Coronation Street set were added to the service in December as part of Google's ongoing expansion of the service.

Antenna Audio

Antenna has produced audio guides for more than 25 years, but recent developments in portable media technology mean that the devices that we're used to hiring at museums and art galleries are less powerful than the mp3 players or phones that we're already carrying around in our bags. So the company has also moved into the realm of iTunes, with a selection of audio mp3s and apps for the iPhone: The Metropolitan Museum of Art Director's selections, highlights from the Rijksmuseum and the Guggenheim's Director's Tour are just three of many available online. Multimedia guides are another strand being developed by Antenna on their handheld smartphone-like XP Vision device; the British Museum use them to provide in-depth audio visual commentaries, while the company also offer the facility for tourist attractions to put together their own guides for the platform.

Node Explorer

The Node Explorer is a location-aware media player that uses GPS technology to provide information at outdoor tourist attractions based on the precise spot that the user is standing. They've been employed at Kew Gardens to make the 132 hectares less daunting for visitors; at the Eden Project, London Zoo and others, with games and quizzes alongside tourist information. Node is working with Nokia to port the its software to the mobile platform, and is looking at providing the means for us all to easily and create location-aware content.

iSpeak

Future Apps in partnership with the Acapela Group has come up with a simple idea executed well: key in a phrase on your iPhone, the translation appears on the screen, and if you're unsure of your pronunciation capabilities, the text-to-voice feature allows you to hold your phone up to someone's face and for the iPhone to announce it on your behalf. Once voice-to-text has been incorporated, we will experience the utopia of us all being able to speak in our own languages, with the smartphone acting as a conduit between us. The only problem is whether those delicate nuances are accurately captured by the software, and an invitation to "meet my husband" isn't translated as "have an affair with my husband".

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks