I Ching, Mark Rylance, and how to choose lunch

'Wolf Hall' actor Mark Rylance has revealed an ancient method of divination, I Ching, helps him to choose roles. A curious Simon Usborne sees how it influences his meal selection

As the scheming man of reason in Wolf Hall, Mark Rylance takes on, among other threats to his (and Henry VIII's) power, the mad prophecies of the superstitious maid, Elizabeth Barton. Yet six centuries later, and long after the age of enlightenment, the actor has credited his reign as one of our great actors to his own reliance on mystical guidance.

But what is I Ching, the means of divination that Rylance talked about on Desert Island Discs on Sunday? The actor said that in the mid-1980s he had faced a dilemma: snap up "a very small part" in a big movie – Steven Spielberg's Empire of the Sun – or follow the sign marked "stage" and take work at the National Theatre.

"I turned to the I Ching and you just ask it, 'Where now?' And it gives an answer," he told Kirsty Young. "The answer it gave if I went to the theatre was 'community', and that swayed it for me. I had never experienced community on film sets. And it was because of that decision I met my wife Claire."

If it's good enough for Mark, what could I, a man now only slightly older than the young actor at a crossroads, divine from the same oracle? I confess I had only vaguely heard of I Ching but more senior colleagues tell me it became quite a thing in the 1960s, with counterculture advocates including Bob Dylan and Leonard Cohen. (Dylan once said that it was "the only thing that is amazingly true, period".)

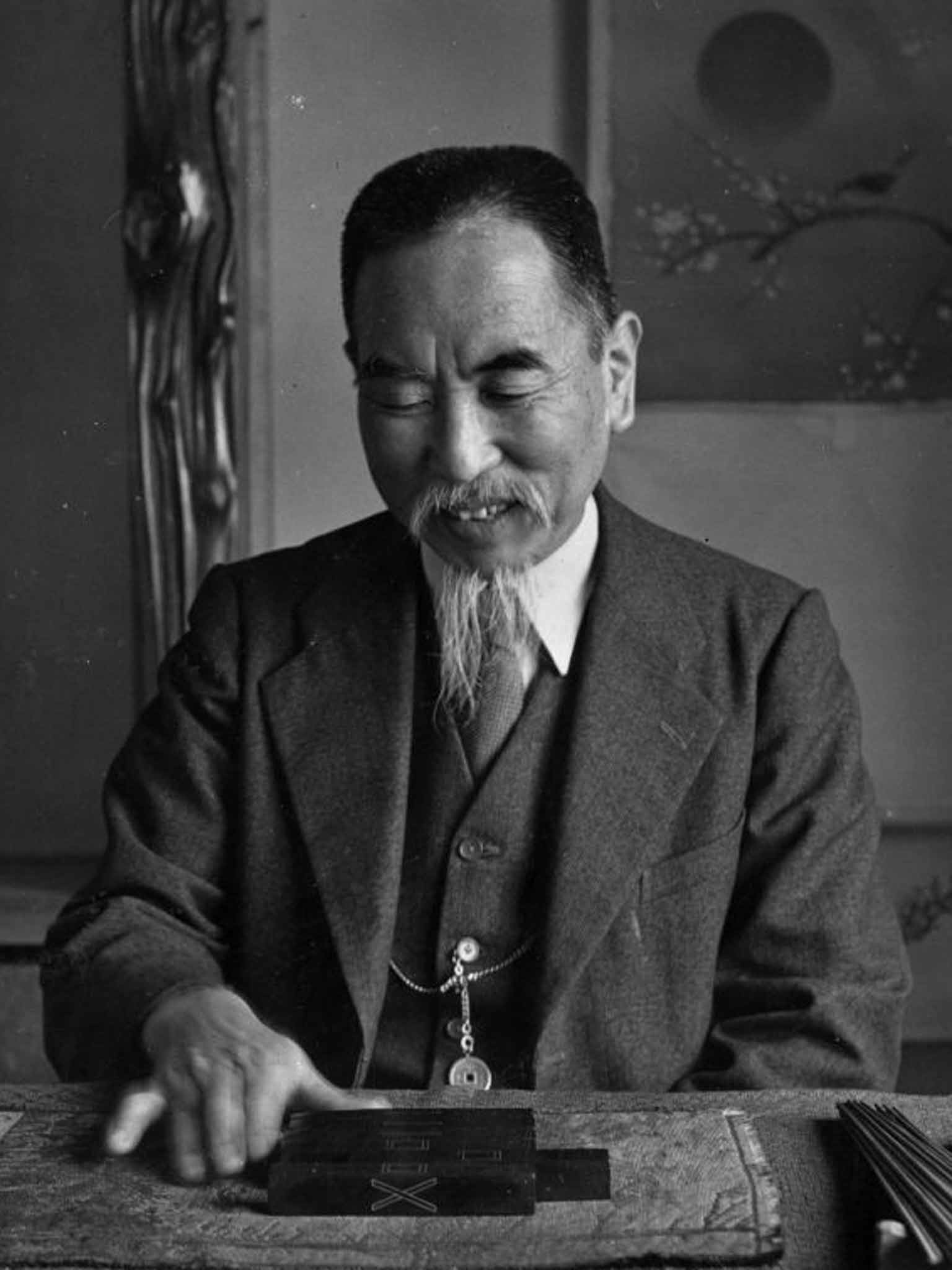

The Waterstones down the road has one copy left of I Ching or The Book of Changes, a best-selling English translation of the Chinese classic, which is more than 5,000 years old. Published in 1989, it carries a foreword by Carl Jung, who likes a bit of spiritualism and appeals to the reader to "cast off certain prejudices of the Western mind" (he means science) "in order to understand".

Reading the thing would probably help, too, but it's more than 700 pages long. So I only have time to dip in for the answer to one of the day's more banal questions. Should I brave the canteen for lunch or spend a bit more money for something nicer outside? This is where coins come in but, struggling to navigate the book, I hit YouTube and find a handy instruction video. I throw my coins. Each combination of heads and tails produces a number, which translates to a line, which can either be long or made up of shorter dashes.

After six throws I end up with what looks like a bit of Morse code, but which is called a hexagram and also produces a new number. But it takes too long, so I go to ichingonline.net, which produces the lines automatically. The answer to my lunch conundrum? "59: Huan / Dispersion [Dissolution]". The website offers an explanation but I consult the book again, rather than waste the £16.99 it cost me. The advice runs to four pages, all apparently based on the lines that my newly divine pennies told me to draw. But only the first bit offers me anything my mind can relate even tangentially to food.

"Wind blowing over water disperses it, dissolving it into foam and mist," it reads. "This suggests that when a man's vital energy is dammed up within him… gentleness serves to break up and dissolve the blockage."

It's clear that I need a gentle lunch to create a release, to break the dam so that my vital energy can be applied to writing about I Ching. This isn't a job for the canteen, which has really gone downhill lately. So, hoping that the blockage is purely metaphysical, I get a reliable roast chicken salad at M&S Food (£4.50 at the deli bit) and feel all the all better for it.

I start to feel bad about my scepticism as I read on, and well-meaning ancient Chinese sages offer me more self-help. There's a bit that says a man (it's always men) must set about dissolving the "obstructions" of misanthropy and "saturnine ill humour" when he "discovers within himself the beginnings of alienation from others". It feels like a warning to disbelievers, and I fear I have alienated Mark Rylance, who I really like. I keep reading before concluding, with respect to those who actually make decisions based on this stuff, that I Ching makes Elizabeth Barton look like a Tudor Richard Dawkins. Thomas Cromwell wouldn't like it either.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies