Inside the sensual world of the synaesthetes: 'I can smell a rainbow'

Holly Williams is a synaesthete, for whom letters and numbers, days of the week and months of the year conjure up a rainbow of colours. Here, she looks forward to a new project that might throw light on this extraordinary condition – and reveals how synaesthesia helps her plan her life...

What colour is the letter F? What texture does a Mozart symphony have? Can you taste the rainbow? If the only thing such ideas suggest is the Skittles ad campaign, you're probably not synaesthesic. But for up to four per cent of the population, such questions make perfect sense.

Synaesthesia is, simply, a union of the senses: a neurological phenomenon whereby one sensory experience involuntarily prompts another. So, the word Pimlico might feel like bubblewrap; the sound of a flute conjures a mauve mist; the letter J can be female and shy; the month of April brings the smell of apples.

Around 70 types of synaesthesia have been identified, and while some are rare, others are surprisingly common. It's likely that you, or someone you know, is quite certain that each letter of the alphabet has a colour, or can describe the images they see when they listen to music.

These are not metaphorical or whimsical imaginings; for synaesthetes, these intertwined sensations are a fact of life, automatic and everyday, unchanging and very real. For me, Monday is red in the same way that grass is green.

Scientists have not always acknowledged the condition: although it was a popular subject in the 19th century, in the 20th it was neglected until the 1980s, and even then it was treated with scepticism, as there was no way to prove it existed. Then, in 1987, advancements in neuroscience led to MRI scans which established that synaesthesia was real: the "visual activity" part of the brain lit up when participants listened to music.

That triumphant research was in part carried out by Simon Baron-Cohen, founder of the UK Synaesthesia Association – and a man who has recently been getting the message out to an audience far beyond scientific journals through his involvement in the research and development of Peter Brook's latest play, The Valley of Astonishment, which won warm reviews when it opened at London's Young Vic last month.

The show brought to life a series of case studies, based on the real experiences of synaesthetes. The main character Sammy finds her synaesthesia helps her to perform astonishing feats of memory – only to her, they're not so astonishing: "It's like breathing," she shrugs. For Sammy, one man's voice comes out as "great yellow splats", while another's is "very orange, very nice". The number 2 is a high-spirited person, but 3 is gloomy; the letter A is "something white and long", while E moves very fast.

Speaking after a performance, Baron-Cohen suggested that while the show was "very true" to the science of synaesthesia, in contrast to the rather dry academic journals he usually writes for, "Theatre crosses the divide between art and science, to communicate the astonishment of the brain, the mind, through imagination."

Recreating the experience of synaesthesia is no easy feat. I saw The Valley of Astonishment and while the play had characters eloquently describe the condition, attempts to render the experience often fell short. For instance, depicting a man who sees colours when listening to music, an actor swept a broom wildly across stage as the lights changed colour, flooding the area in purple or red, to live jazz piano and cymbals. But a complex, shifting piece of syncopated music is unlikely to provoke a simple block of red. The synaesthesic experience is far more nuanced.

Brook is not the only person to try to recreate the condition: one of the most famous synaesthetes was the Russian abstract artist Wassily Kandinsky, whose paintings captured his vision of music; he described his lines and shapes on a canvas as musical notes that "sing" together. Arthur Rimbaud, in his poem "Vowels", meanwhile, catalogued the hues and textures of letters: "A black, E white, I red, U green, O blue: vowels/ Some day I will open your silent pregnancies."

The French composer Olivier Messiaen heard chords in colour, and more recently, musicians Pharrell Williams, Frank Ocean and Kanye West have all described how sonic and emotional experiences have a colour. Dev Hynes, the songwriter and producer, devoted a TED talk to the topic; and Richard D James – aka Aphex Twin – has spoken about using synaesthesia to write songs, saying that certain sounds produce strong smells.

When it comes to recreating such complex relationships, modern technology can be a friend. Composer Nick Ryan is making full use of this potential with a new piece called Synaes that will premiere at the Roundhouse in north London, as part of Imogen Heap's Reverb festival next month. Ryan is working with the digital artists Quayola & Sinigaglia, who have developed 3D visualisations that respond to music. When he first saw Davide Quayola's work, which is tactile as well as colourful, it resembled what Ryan sees in his head when he hears music. There will also be an olfactory element, with smells aligned to the sounds and images wafting over the audience.

Ryan says he has always heard music when he watches animation and graphics – "Images have auditory equivalents," he tells me – but this project involves working the other way round: writing the music first, then matching images. "What sounds provoke visualisation? What sounds are tactile? I went outside and looked around to see what stood out to me," he explains of his work. "Five categories emerged, that made different types of sound: colour; texture (both to touch and see); rhythmic or patterned [surfaces]; curves; and size or scale. So I made this taxonomy and used it as a starting point for five four-minute sections of music. It expresses my experience, but it's very abstract – a sensation scrapbook in which the audience is immersed."

Ryan also has grapheme-colour synaesthesia – letters and days of the week have a colour – which he'll attempt to reflect aurally, too. "So Saturday is red, pencil-red, quite dark," he says. "The sound is very deep, very loud; volume is important. It's harmonious – a broad harmony – fifths and fourths." Monday is bright yellow; it has a high sound, and also a sharp, lemony smell.

The next step will be to work with Quayola & Sinigaglia to develop images that respond to those sounds in ways that seem to fit with Ryan's inner experiences. So Synaes really should provide a window on to one's man's unique view of the world. But he also hopes such multimedia artistic responses will allow us all to experience "technological synaesthesia" of a kind: "We're now able to align sensory media very closely. Technology lets us have multi-sensory experiences – a cultural synaesthesia."

'Synaes' is at the Roundhouse, London NW1 (roundhouse.org.uk), on 23 August

Holly Williams has experienced synaesthesia all her life – though she didn't realise it was unusual until she discovered a fellow synaesthete in Vladimir Nabokov. Until then, all she knew was that Monday was red, Tuesday pink…

Like Nick Ryan, I have grapheme-colour synaesthesia: letters, numbers, days of the week and months of the year have colours; words take on tones based on the prominent sounds and letters within them. But, of course, I differ from Ryan in the colours I "see" – my Monday is a bright bold primary red, not yellow. How exactly I see the colour is a mystery even to me– it just sort of is. There are thought to be two ways of seeing within synaesthesia: either in the mind's eye or projected on to the external world. I certainly have the former – just a sense or knowledge that, say, nine is a mustardy yellow-brown.

In my day-to-day life, it has little impact. It's just there, in the background. As you know that 2 + 2 = 4, but don't think about it very much, so I know that October is white, but don't dwell on it. Although I do remember once being troubled on a foreign subway – all signs and maps for the A line were bright green, and the C line was red. Given that the letter A is – obviously! – bright red, I was confused, and would at times start to follow the colour instead of the letter.

I think I've always had synaesthesia. But for a long time, it didn't occur to me that this was anything unusual – like most synaesthetes, I just assumed everyone had it. I have vague memories of writing a poem about the colours of the days of the week when I was young, and discovering my mum definitely thought they were different hues. Although we both see Wednesday as a dark green, she thinks Sunday is yellow. This is clearly madness: Sunday is an inky purple.

But the fact that this was "a thing" only came into focus for me when I was a student, studying Nabokov in my final year of university. I read that he had something called synaesthesia. He wrote: "My wife has this gift of seeing letters in colour, too, but her colours are completely different… We discovered one day that my son, who was a little boy [sees] letters in colours, too… one letter which he sees as purple, or perhaps mauve, is pink to me and blue to my wife. This is the letter M… Pink and blue makes lilac in his case… as if genes were painting in aquarelle."

I was very taken with this charming story, and went back to my own family to ask again what colours they saw – my dad doesn't have it and my brother thinks that he had it as a child, but it's faded out now. I also started talking to friends, many of whom expressed bemusement – and, yes, scepticism – at my assertion that, say, 4 is blue. They wanted to know what colours their names were, and weren't always best pleased with the answers. It's nothing to do with personality, I insisted: Ralph's not a grey person, it's just that the capital R is a strong, grey presence. It's instinctive, not interpretive.

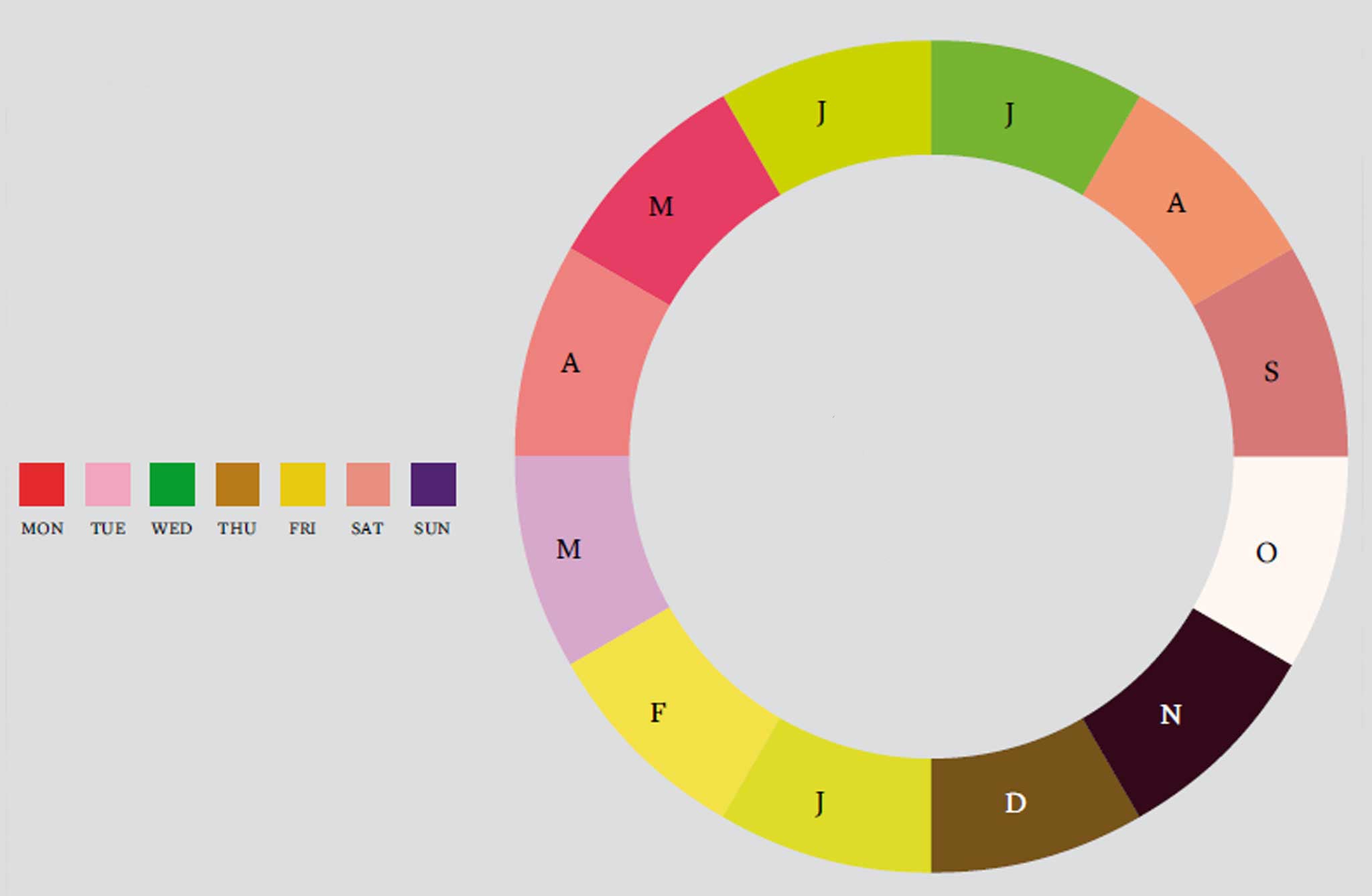

Since then, synaesthesia has fascinated me. I recently read an article that listed various types, including sequence-space synaesthesia, which allows you to see sequences such as numbers, days and months in a spatial arrangement. Again, this was something I presumed everyone had: for me, the days of the week go from left to right, and the months go round in a wheel, with January meeting December in the bottom centre. Oddly, I don't have this for numbers. So when I think "I'm meeting Lizzie on Thursday", my mind jumps to a low space in front of my torso, towards my right. (Thursday is brown; Lizzie is blue).

This can be useful in everyday life – I can park things in a spatial diary. Not that I am guaranteed to remember them… the incredible feats of memory that Sammy achieves in The Valley of Astonishment are, sadly, out of my reach. For me, synaesthesia just feels, well, very ordinary.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks