Postnatal depression: Inside the clinic that could provide a blueprint for future treatment

Last December, Charlotte Bevan and her baby were found dead in the Avon Gorge. Ahead of an inquest into her death, Sophie Goodchild gained access to one of the few specialist mental-health units that treats women for postnatal depression alongside their infants – and heard the story of Rupa, a mother who entered the unit on the verge of suicide and emerged on the road to recovery

From the outside, the Bethlem Royal's Mother and Baby Unit appears unremarkable. Tucked away in a corner of the hospital site, the red-brick building looks more like a training centre. But it's what happens inside that goes beyond the ordinary. Here, pregnant women and new mothers are rescued from the bleakness of despair, their sanity restored by round-the-clock care. In extreme cases, this specialist support can mean the difference between life and death.

To be admitted to the Bethlem, you must have been diagnosed with a severe perinatal mental illness; postnatal depression (PND) is the most common. PND is not to be confused with the "baby blues", that teary hormone-induced mood crash that fades a few weeks after a birth. At its most acute, PND destroys relationships and families; the long-term financial cost alone to society of poor mental health among new mothers exceeds £8bn.

For the thousands affected, it can feel as if they are losing their mind. It leaves women overcome with anxiety, tormented with thoughts of self-harm towards themselves or their babies.

Yet despite the fact that one in 10 mothers suffers from PND, mental illness is a taboo that still silences many of them. The experience of motherhood has become as airbrushed as the thighs of a supermodel in a glossy magazine. Such is the shame at not meeting society's impossible expectations that women frequently blame themselves for being less than perfect and delay seeking help, sometimes for years.

Next month, inquests are expected to resume into the deaths of Charlotte Bevan and her four-day-old daughter, Zaani Tiana. Until then, no one knows just why the charity worker walked out of a Bristol maternity hospital on a freezing night last December, to be found dead two days later in the Avon Gorge, the body of Zaani nearby. However, her partner, Pascal Malbrouck, has said she was sleep-deprived and depressed, in addition to dealing with a diagnosis of schizophrenia. There have even been suggestions that this 30-year-old first-time mother was worried that her diagnosis could have resulted in her baby being taken into care.

This heart-breaking case and others like it raise serious concerns about the lack of specialist support for mothers suffering a mental-health crisis. Women are 33 times more likely to be admitted to a psychiatric unit after having their first child than at any other time in their lives. Yet there are only 17 inpatient units around the country, including that at the Bethlem Royal Hospital in Bromley, offering dedicated support and, crucially, allowing women to be admitted with their babies.

Any expert will tell you that keeping mother and baby together is important not only for a woman's recovery but for mother-child bonding and an infant's development. "The relationship between mother and baby is critical to both at this early stage – even mothers who are really unwell," says Dr Alain Gregoire, a consultant perinatal psychiatrist who chairs the Maternal Mental Health Alliance. But large swathes of the country, including Devon, the Thames Valley, and Wales, do not have mother and baby units, so patients there are forced to travel miles for treatment. Others end up on overstretched adult psychiatric wards without their babies and without specialist care.

Rupa Kamat Platjouw was one of the fortunate ones – she got the help she needed, eventually. Like Charlotte Bevan, Rupa was a first-time mother when she gave birth, in November 2009. There was no question that her son, Zane, was much wanted and planned. Indeed, Rupa and her husband, Vincent, attended all the antenatal classes, read the right books and could not wait to become parents. Then came the birth – a difficult and traumatic experience: Rupa suffered third-degree tears and had to have surgery.

Returning home with her new baby, she felt overwhelmed. Neither her family nor Vincent's live close, so they couldn't be on hand immediately. "Zane was perfect and the hospital did their best, but I felt detached, anxious, numb. I got it into my head that he was different from other babies. There was a constant negative discourse in my head," recalls 40-year-old Rupa, who had worked in the City before having children. Recognising the symptoms of PND, her GP k prescribed an anti-depressant. But her illness had a firm grip on Rupa, and she twice attempted suicide. "I thought my son and my husband would be better off without me," she says.

The first years of motherhood are billed as the happiest time of a woman's life – but for Rupa, they were dominated by her illness. Medication kept her functioning but was no cure. Neither was cognitive behavioural therapy, although it was a help. Then Rupa became pregnant again and was plunged once more into severe crisis within weeks of giving birth. Her son Leonardo was born in June 2012, and the symptoms Rupa had been managing escalated to, she says, "magnificent proportions". This is when she was referred to the Bethlem, part of South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust.

"There was one bed available and they told me I'd have to get there in the next half an hour," says Rupa. "I knew I had to do it to give my husband and family respite." For the first few weeks, she was bed-bound, suicidal. But gradually the benefits of specialist support, and meeting other mothers like her, helped her heal.

"My illness had left me convinced there was something wrong with Leonardo. But when person after person, including a consultant who was called at 3am, failed to confirm my fears, I slowly began to realise they were just thoughts and not the truth. That was the turning point." The unit also provided round-the-clock care for her baby, which was vital in the first few months, when she was so ill she was capable only of breastfeeding, changing and bathing him.

Now fully recovered, Rupa is a happy mother of two who works as a lifeguard, plans to retrain as a teacher and feels "indebted for the support I received". That support extends to family, too, including Vincent, 37, who admits he would not have been able to care for his infant son alone. "The situation would have been unsustainable," he says. "Leonardo being with Rupa meant they could bond while she had space and time to get better. And Zane and I could go and see Mummy every evening." Before Rupa was admitted to the Bethlem, there was support, but it was more about "containing, rather than getting better", Vincent tells me. "It felt as if we were just surviving from day to day."

Every woman admitted to the Bethlem is assessed by an expert team of psychiatrists, psychologists and nurses. Her full health history – both mental and physical – is analysed, along with her relationships, such as those with family and partners. Treatment can include medication and a range of therapies, such as psychotherapy. The unit also provides meditation, art therapy and nature walks in the 270 acres of green space that surround the Bethlem. During my visit, I'm shown around the spacious nursery where women play with and tend to their babies as they would at home. The focus on the mother-child relationship is a crucial part of recovery – staff even take women out on bus journeys with their infants to help them overcome anxieties about the daily demands of motherhood.

"Mothers often arrive here feeling they're not 'good enough', that they can't do things for themselves, but they feel more empowered when they're treated with baby," suggests Dr Trudi Seneviratne, consultant psychiatrist at the unit. There is also video "feedback" with a developmental psychologist, which involves patients being filmed interacting with their babies. Dr Seneviratne plays me one of these "baby whispering" sessions, in which a mother smiles and coos at her child, who smiles back. The purpose is to challenge negative assumptions – such as "my baby doesn't look at me" – that can seem all too real when you're sick.

The reasons behind PND and mental illness in pregnancy are complex – a lack of family support, money worries and sleep deprivation can all be contributory factors. Another is the rise in older first-time mothers. One in five births in 2013 was to women aged 35 and over, compared with only one in 10 two decades before. The proportion of births to women over 40 has also doubled. For women who have been in control of their own lives and careers for so long, adjusting to the demands of an infant can be overwhelming.

"Women are having babies later and this does increase the risk of depression," agrees Dr Seneviratne. "They're used to achieving in k their careers, and expect to get it 'right'. They're disappointed if it doesn't go as the book says. And they may also find themselves isolated and struggling without a support network."

The average stay here is eight weeks, and discharge is staggered: one day at first, then a weekend, with staff going out into the community to support this. Bethlem takes referrals from all over the country and its 13 beds are always full – proof that such one-to-one support is in high demand. Indeed, the Maternal Mental Health Alliance estimates a current shortfall of 60 mother-and-baby unit beds across the UK.

To address this shortage, it is calling for a national strategy, along with more specialist perinatal mental-health teams in the community so that, ideally, women never get sick enough to need a mother and baby unit. It is "simply not acceptable", says Dr Gregoire, that not all women have the support necessary. "If you were talking about a lack of maternity services it would be a national scandal," he adds.

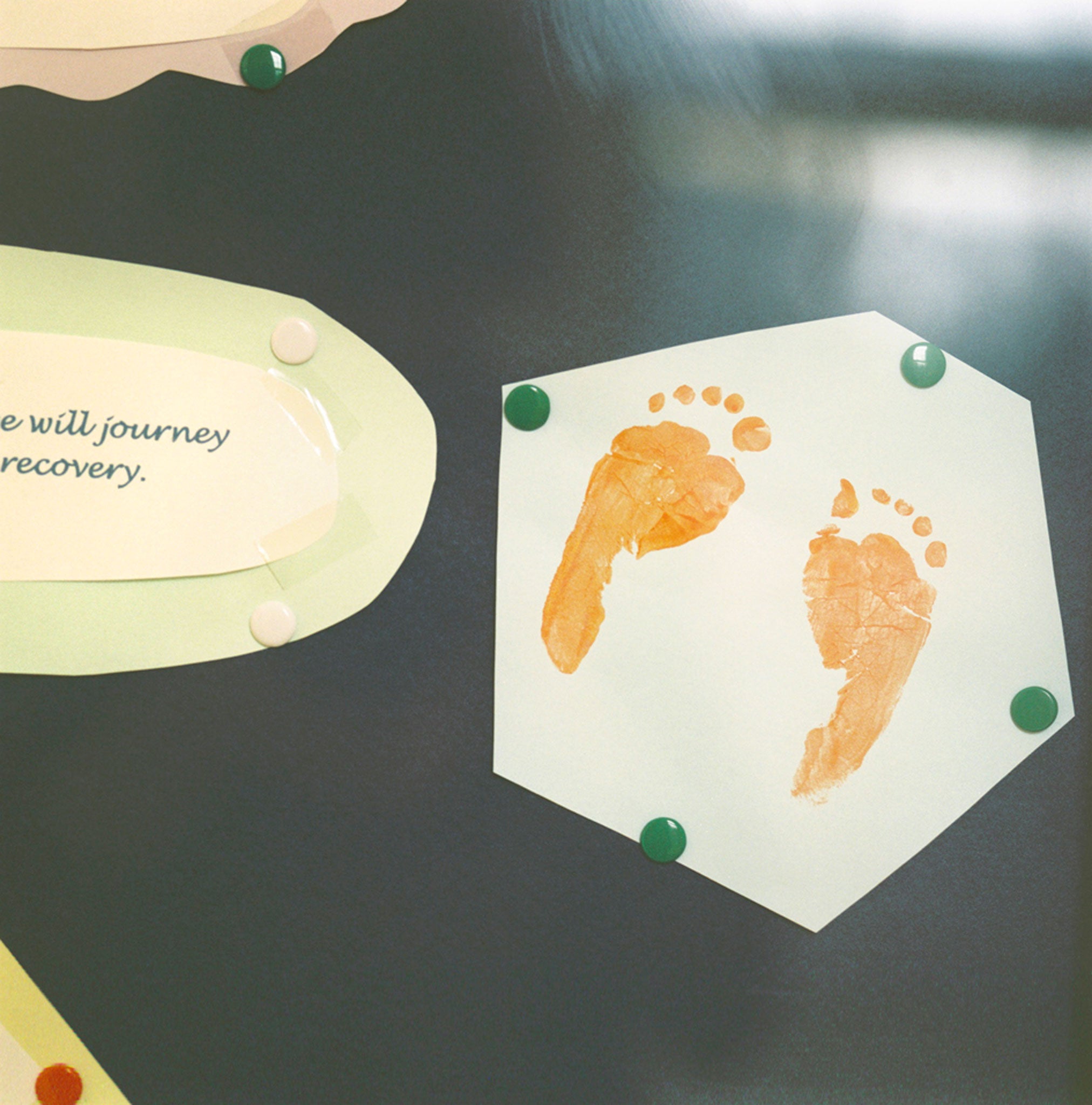

Pinned to the wall of Dr Seneviratne's office are cards from women and families helped by her and her team. My eye is drawn to one in particular. From a mother, the note sums up why the work here is so important. It says, simply: "Thank you. The unit saved my life."

Rupa Kamat Platjouw is running the London Marathon on 26 April on behalf of Samaritans. To sponsor her: justgiving.com/Rupa-Kamat2

Life at the unit: Rupa's experience

'It wasn't so much that I wanted to die; I just didn't want to live. A head that wouldn't stop processing ruminating thoughts. A level of anxiety and breathlessness. A false smile and desperate need to get through the day quickly. A dread that this feeling is here to stay. A longing to go back to bed. To close my eyes and hope for that miraculous change of mood that seldom came.

"Now I know I had an illness, but I thought it was my personality, that I was 'messed up'. Being ill made no logical sense – I was happily married, had a planned pregnancy and gave birth to a healthy baby, albeit after a traumatic birth.

"I never believed I'd recover. I told them at the Mother and Baby Unit, 'I've tried every anti-depressant, every therapy – you've not had anyone like me.' But I did get better. There's nothing like the support they give. You meet other mums like you, so you realise you're not alone. You're surrounded by specialists who know what you're going through. And my son was able to feel, smell and hear me, which was so important.

"At first I was able only to breastfeed, change and bathe him, as I was so depressed. But by the end I was solely responsible for his needs – and enjoying it. To those out there in that dark place, I want to say, it's OK, you're not alone, you can get better – just hold on."

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks