The hereditary principle: family fortunes

A fascination with romantic royals and celebrity dynasties might seem innocent, but it reveals that the hereditary principle is still shaping our society, argues Ben Chu

We are drowning in royalism. First came the gush of national enthusiasm at the announcement of the impending nuptials of Prince William and Kate Middleton. Then we were drenched in critical acclaim and publicity for The King's Speech. By the time the royal wedding comes around in April, our heads will be well and truly under monarchist water.

Resistance against this royal resurgence seems to be futile. The Labour MP Keith Vaz yesterday tabled a bill in the House of Commons to scrap the law of primogeniture, which guarantees male heirs to the throne automatic preference over their elder sisters. The chances of this reforming legislation being passed are as great as seeing a guillotine erected in front of Buckingham Palace in the near future.

The cultural manifestations of royalism are perhaps the most powerful. The King's Speech is a tale of how the Duke of York (the future King George VI), played by Colin Firth, tackled his debilitating stammer in the inter-war years with the help of an Australian speech therapist. The critics are right: Tom Hooper's film is an expertly crafted piece of cinema with some fine performances. But it is also unadulterated royal propaganda. The Duke and his wife, the future Queen Mother, are presented as aloof but also witty and, at heart, warm. The film ends with the new monarch, having tamed his stammer, successfully rallying the British Empire in a 1939 radio broadcast for a conflict against Nazism. We are informed in the final words of the movie that King George VI became "a symbol of national resistance" throughout the war. So never mind Winston Churchill (a bit-part player in the film). It was the Royals wot won it!

David Seidler's script also treads as delicately as a courtier around the not entirely pukka behaviour of the royals in the 1930s. The pro-appeasement views of the future Queen Mother and the cosy meeting between George's elder brother and Hitler in Bavaria in 1937 are never mentioned. "Backstairs" Billy Tallon, the late Queen Mother's loyal page, could not have done a more accomplished job of covering up royal indiscretions.

But such details of history matter little because royalty is now "box office". Indeed, it has been for some time. Over the past 15 years, both Elizabeth I and Victoria have been the subjects of films twice over. There have been television biopics on Edward VIII and Princess Margaret. Stephen Poliakoff made a drama about "lost" Prince John.

Even the present crop of royals has been given the celluloid treatment. I've always thought that the great achievement of our present sovereign, Elizabeth II, is that she comes across as the most boring person in the country. Even republicans find it difficult to build up much animus against her. Yet 58 years of dullness from our sovereign did not stop Stephen Frears' 2006 film, The Queen, set in the wake of the death of Diana, Princess of Wales, becoming a critical hit and a commercial triumph. Even the most uncontroversial, most inoffensive monarch can be made to glitter by the alchemy of the cinema. Even a vegetable in a crown can draw the crowds. It will not be long, surely, before we get a moist-eyed biopic of the late Queen Mother, featuring her brave tours of the bombed-out East End during the Blitz.

These cultural celebrations of royalism (and the public appetite for them) have a significance. For what is royalism, once you have stripped away all the fine words about tradition and political stability, but the fetishisation of the hereditary principle? And what is the hereditary principle but the assertion that it is the natural order for power, wealth and talent to flow between generations of the same family? This reactionary philosophy might not be quite antithetical to democracy. But they certainly make for uncomfortable bedfellows.

And this resurgence of respect for the hereditary principle goes beyond enthusiasm for royalty. The virus has infected other areas of our culture. The children of performers and celebrities are now commonly regarded as inheritors of their parents' talents. To illustrate the point, let's take a quick walk through popular culture. Here on your left is Jaime Winstone, daughter of actor Ray, chosen to present a recent BBC documentary on oral sex. On your right you see Lily and Alfie Allen, successful singer and actor respectively, both the offspring of comic performer Keith. And watch out ahead, because there's an avalanche of Rolling Stones progenies. Flick through a glossy magazine and it's impossible not to get cut on some Jagger edges, whether it be Jade, Elizabeth or James.

Cross the Atlantic and you find 10-year old Willow Smith, daughter of Will, already with an established music career. Don't forget her 12-year-old brother, Jaden, who last year featured in a wholly unnecessary remake of The Karate Kid. And look: Madonna's 14-year-old daughter, Lourdes, has designed a line of clothing for Macy's department store. They are polymaths, these celebrity scions: singers, actors, models, television presenters, jewellery designers. Or, like royalty, they can merely be famous for being famous. Indeed, in some cases the offspring of celebrity royalty and the traditional variety go to the same expensive private schools.

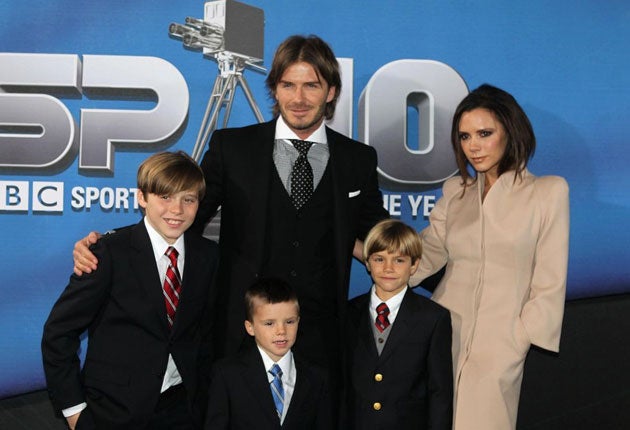

And the hereditary fever is deepening. Romeo Beckham, the eight-year-old son of David, was presented earlier this month as one of the best-dressed males in the country by GQ. David Walker-Smith, menswear director at Selfridges, told the magazine: "He's experimental, quirky and fun, and his style has nothing 'Mini-Me' about it. It's me-me!" It gets creepier. Suri Cruise, four-year-old daughter of Tom, has been congratulated for her fashion choices. If you don't find that disturbing I'd suggest that you have a chip missing.

This fawning over the children of celebrities is not just a reflection of the tastes of magazine editors, casting chiefs, advertisers and music executives. Depressingly, there is a public appetite for showbiz scions, just as there is a burgeoning market for all things regal. Why else do we still see the appallingly talent-devoid Osbourne family (Ozzy's brood) in magazines or television shows? Debenhams says parents now spend up to £427 a year on clothing their little girls to ensure they "keep up with the Cruises". The evidence suggests that, sadly, the public buy into this hereditariness.

I suppose the counter-argument to the idea that we are living through a dark age of inherited celebrity and talentless fame is that it was ever thus. There have certainly always been diehard royalists. Charles and Diana's wedding inspired a nationwide round of forelock-tugging 30 years ago. And there have always been showbusiness dynasties, too, from Judy Garland and Liza Minnelli, to Kirk and Michael Douglas, to the Redgrave clan.

Corners of democratic politics have long looked like a family business. The Kennedys were a de facto American royal family. More recently, we have seen the dynastic tussles between the Bushes and the Clintons. The mayoralty of Chicago has been the property of the Daley family for almost half a century. One member of that tribe was recently appointed Barack Obama's Chief of Staff. And here in Britain, hereditary politics is of an even older vintage. From the Pitts to the Chamberlains, to the Benns, our politics too has had a dynastic tinge.

Yet something feels different about the modern variety of genuflection before birthright. Royal sycophancy seems to be less challenged than ever. I suspect that 30 years ago, the idea of the British public empathising with a stammering 1930s monarch would have seemed bizarre. And yet here we are in 2011, feeling George's pain en masse. During the Queen's silver jubilee in 1977, the Sex Pistols released their scabrous anti-establishment anthem "God Save the Queen". Does anyone seriously expect a similar act of cultural lèse-majesté for the 2012 diamond jubilee? And in showbusiness has the gulf between ability and acclaim ever been so vast? Be honest: how much talent is there among today's celebrity offspring? Would you have much left over after filling a thimble?

The present promotion of the hereditary principle has a post-ideological feel to it. Once, our cultural arbiters – the editors, the television producers, the music executives – might have been troubled at the thought of using Royals and celebrity brats to sell magazines, attract viewers or shift CDs. But now, profit trumps all. Taste-makers are no longer royalists or republicans, no longer conservatives or egalitarians. Principles, of any sort, are so passé. It's all about the money. Put the children of the famous on the front of magazines? If it moves copies, why not? Fill the schedules with royal trivia? If it attracts viewers, what's the problem?

An illuminating moment in our cultural life occurred late last year when the triumvirate of David Cameron, David Beckham and Prince William were sent to the headquarters of Fifa, the global football governing body, in Switzerland to lobby for England to be made host of the 2018 World Cup. Leave aside the Prime Minister and consider our other two "ambassadors". One is a superannuated sportsman whose talent never justified his worldwide fame. The other is a man whose sole achievement in life is to have sprung from the right womb. Yet this was almost universally regarded as "the best of British" on display. It was felt (wrongly, as it turned out) that Fifa delegates would be unable to resist the pair's combined charismatic force.

So what explains it? Where does this public appetite for dynasties, this preference for lineage over ability, come from? It's possible to concoct a Marxist-style explanation, to identify underlying economic causes. There has always been a human fascination with power. And in modern Britain, money and connections (which Royals and the children of celebrities have in abundance), rather than talent, are the keys to power. The return of respect for the hereditary principle is thus a reflection of stagnant social mobility. If you turn people into serfs, you are going to see a return to a feudal mentality.

I half-believe this. Ours is certainly a calcified society. A report on social mobility by the former Labour cabinet minister Alan Milburn three years ago pointed out that 75 per cent of high court judges, 30 per cent of MPs, 45 per cent of top civil servants and 55 per cent of journalists attended private schools (as against 7 per cent of the general population). It seems to me that such high levels of inequality of opportunity – whatever the causes – are likely to produce some unhealthy mass psychological reactions.

Yet I don't have full confidence in this explanation of why we genuflect before boring royals and feeble celebrity scions. It does not explain the parallel public fascination with reality television stars and the products of X Factor-style karaoke competitions, who have no money or connections and whose careers have the lifespan of mayflies.

Moreover, perhaps this cultural virus is on the verge of being defeated by egalitarian antibodies. Maybe a reaction is brewing. A tsunami could be gathering pace far off in the cultural ocean that will sweep away all the quasi-aristocratic lineages, all the talentless progenies that hover over us. Might a new Johnny Rotten emerge to rain on the royal party next year? We can dream.

But right now, we seem locked in the age of the hereditary principle. Look at David Beckham and you see a king in all but name: he is revered not because of what he does, or what he has accomplished on the sports field, but because of who he is. And the signs are that, in time, his offspring will be honoured in turn. Seeing Beckham photographed across a table from Prince William at the Fifa meeting in Switzerland last month brought to mind the end of George Orwell's Animal Farm: "The creatures outside looked from pig to man, and from man to pig, and from pig to man again; but already it was impossible to say which was which." We are all under the hereditary yoke now.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks