The poster boy for motor neurone disease

It's the illness that strikes without warning and can kill within months. So how does Alistair Banks stay so optimistic? Nick Duerden reports

A little over a year ago, Alistair Banks, a then 39-year-old teacher living and working in east London, became aware that he was developing a curious limp in his right foot. "When I went up the stairs at school, it kind of... flopped," he says. As men, so faithful to their stereotype, perpetually do, he ignored the problem, confident that it would go away in that non-specific manner like so many of our daily irritations.

It didn't. He next realised that the cycle to work was taking longer each morning, and then, shortly after, he noticed that his right thigh was significantly smaller than his left. "I'd somehow lost a lot of weight from it, and very quickly." He promptly went to his GP.

"My doctor said pretty much straight away that it looked sinister," he recounts. "He ordered some tests, and made me promise not to go on to Google."

A whole battery of tests followed, and a succession of hospital appointments. En route to one by Tube, he saw a billboard advert for somebody called Patrick the Incurable Optimist, an artist in his late 30s who had recently developed motor neurone disease (MND). In the text, Patrick insisted that he was not to become a passive victim of it but to remain proactive, and so set himself the task of completing a series of portraits before his condition made it impossible. It was while reading all this that Alistair experienced the most disconcerting stab of recognition. Any further tests, he realised, were academic.

"But even when the diagnosis was finally confirmed, it was still, well... it was absolutely devastating," he says. A year on, it still is. "At least once a day it slaps me across the face when I least expect it. I am 40 years old, and I have motor neurone disease. It's like it hasn't quite sunk in yet."

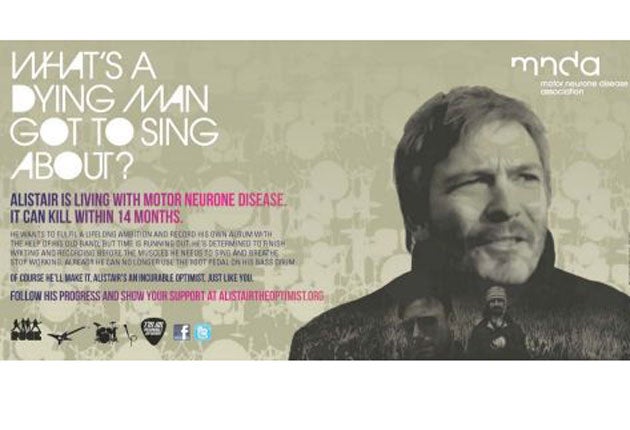

In June this year, the Motor Neurone Disease Association launched its latest awareness-raising campaign for 2011. Alistair Banks was its new face.

Motor neurone disease currently affects somewhere in the region of 5,000 people in the UK. Each day, five people die from it. It is one of the more devastating conditions, and also one of the more mysterious: though 5 per cent of cases are hereditary, 95 per cent strike without any known reason. It is also, says the MND Association's spokesperson Mel Barry, "incredibly cruel. It takes away the ability to talk, to walk, to eat and breathe, and its progress tends to be both rapid and merciless."

Half those affected die within 14 months of the diagnosis, the other half within two to five years. The scientist Stephen Hawking is not only the world's most famous sufferer, but also its longest survivor. That he has been blighted by MND for close to 50 years now, notes Barry, "is very, very rare indeed".

"We fund research all over the world," she continues. "And though there is no known cure yet, we are trying to piece together the jigsaw, to help sufferers to live longer, and also to cope with it better." But as a charity, they rely largely on donations. Hence Patrick the Incurable Optimist's public campaign, and now Alistair's.

"I haven't seen the billboards in the flesh yet," says Alistair. "I'm not sure how I would react to see myself plastered all over an underground station. Friends and family have seen it, and they say it's quite a shock. But then I suppose you need to shock to get the message across, right?"

It is a bright, sunny day in a small village in Somerset, and Alistair Banks sits in his wheelchair in the house he shares with his wife, Alice, and two children, Finn, seven, and Freya, three. A geography teacher in east London for 14 years, he and his wife began to crave, as he puts it, "some country living" at the beginning of 2010. Alistair applied for a deputy head's post at a local school and got it. It was only once the relocation was complete that he began to develop symptoms of his illness.

"I did carry on teaching at first," he says, "and I managed, for a while at least, with a walking stick. But then it became two, and then a Zimmer frame."

He was forced to stop altogether shortly after his 40th birthday in November, and his wife, also a teacher, stopped as well in order to become his full-time carer. "That's pretty much our life now: Alice rushes around on the school run, and then she comes back to look after me."

It is difficult, he admits, to remain positive under such conditions. "Oh, it's all there, really, all the emotions, all the time: anger, fury, optimism, defeat. Also: why me? But then that attitude doesn't help anyone, least of all me. I have responsibilities still, to myself and my family, and so I'm doing my best to keep myself occupied. It helps."

Over the past few months, he has become a passionate campaigner for MND, and has taken part in several charity events to help raise funds. But he has also undertaken more personal projects. Twenty years ago, the trainee teacher had aspirations of becoming a rock star, and played drums in a succession of indie rock acts. Now, while he still can, he wants to get the band together one last time.

He grins. "Emotional blackmail works wonders. Though they are all busy with their own lives now, they've each made time to come up to the house for songwriting sessions and rehearsals. Which is great, because it really is very much against the clock for me. As I get weaker, I can only play for briefer and briefer periods, and I've also had to adapt my style." He is no longer quite as loud as he once was, he continues, "but then none of us are. We're strictly country-folk now, and far quieter. Acoustic; no amps. It suits us."

The band, Floatilla, have recently been offered free use of a recording studio near Bath, and they hope to complete an album of original music soon. It will be his legacy. "I can't tell you how therapeutic it is," he says. "We get together, we play, and we laugh a lot. It's a much-needed distraction."

Elsewhere, distraction is difficult to come by, MND is the inevitable focus of so much of his life now. He has counselling sessions, attends support groups and is in touch with other sufferers. His house has been modified to make navigating his wheelchair within it easier, and he hopes soon to get a car that will accommodate his wheelchair, and which will, he says, "make days out with the kids easier. That's important".

In the months since the billboards went up, Alistair's life has changed. A number of television documentary makers have contacted him wanting to tell his story, and he has found himself in the curious position of being thrust front-and-centre of an association, and an illness, that, just 16 months previously, he barely knew existed.

"The support I have received via my blog has been amazing," he says. "Friends, strangers, old pupils and people I haven't heard from in years have been in touch to offer support and kind words. Each morning I log on to find another surprise waiting."

And it has reminded him that even in the 21st-century, in a "heads-down, get-on-with-it society", there is still so much understanding in people, so much kindness, and empathy, and generosity. "That's something that keeps me optimistic," he says. "And I'm grateful for it, I really am."

For more information: www.alistairtheoptimist.org

MND: the harsh truth

* Motor Neurone Disease (MND) is a progressive neurodegenerative disease that attacks the upper and lower motor neurones. Degeneration of the motor neurones leads to weakness and a wasting of muscles causing increasing loss of mobility in limbs and difficulties with speech, swallowing and breathing. There are four main types of MND, each of which affect people in different ways.

* While MND will affect everyone differently, it is usually very gradual. Early symptoms may simply be tiredness, while clumsy fingers and a weak grip can also be a sign. Others symptoms include muscle cramps and spasms as well as stiff joints.

* Not infectious or contagious, MND is most common between the ages of 50 and 70 and it affects twice as many men as women. About 5,000 people have MND at any one time in the UK. Five people die as a result of it every day.

* It is not understood what causes MND and there is no known cure. Once diagnosed it is not possible to prevent it from developing. Various treatments can slow down the progression of the disease for some people and occupational therapy can help, but it is always fatal.

Gillian Orr

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks