'When is mummy coming back?'

Widowed fathers of young children have to face not only their family's grief, but practical and domestic challenges, too. Rob Kemp talks to men left behind, to discover how they cope

No matter how competent the modern hands-on man about the house is, nothing seems to be able to erase the stereotype of what life's like for kids when father is left in charge. The mere mention of "dad's watch" conjures up visions of all hell breaking loose the moment mum leaves the house. This "chaos" theory is portrayed in the home life of Joe Warr and five-year-old Artie, father and son characters played by Clive Owen and Nicholas McAnulty in this month's movie release The Boys Are Back.

Without Katy, Artie's mum, around, mess soon becomes the norm. Housework, healthy diets and hygiene have left the home with her. Dirty plates disappear into the back of cupboards, school clothes are whatever's the least dirty and tomato sauce is a breakfast staple as Warr adopts a "say yes to everything" policy. These "semi-feral" habits – as the visiting parents of Artie's friends call them – are sadly a side-effect of a carefree approach to fatherhood that Warr adopts because Katy has died. The film is based upon a memoir by Simon Carr, The Independent's political sketch writer, whose wife Susie died from cancer in 1994, leaving him to raise his then five-year-old son Alexander along with Hugo, Carr's 11-year-old from his first marriage.

The Boys Are Back not only paints a picture of how the relationship between Carr and his sons developed following the sudden death of his wife, but it also offers an insight into how thousands of young men and women each year come to terms with the deaths of their partners when left to raise young children alone.

"Young fathers especially in this situation often face the added struggle of trying to find some kind of practical support network beyond that of the immediate family," explains Linsay Black, of the Way Foundation, a support group for bereaved parents. "In many cases the man has not only lost his wife but also his best friend – the only person he has really opened up to." Linsay, herself widowed with a two-year-old daughter, says around 15 per cent of the group's members are men. "It's a fact that women are more likely to be widowed than men. But it's more often the fathers who are in need of help and practical advice with day-to-day stuff. They ask, through the website's message boards, about potty training or for answers to questions like 'when I take my little girl to the toilet, should I take her in the men's or women's loo?'"

Linsay points out that the traditional parenting roles make things even harder for men when thrown into this situation. "Until the death of their child's mother they've often had quite a distinct role, or they're the 'fun dad' – being a playmate for their kids at weekends and after work. Now they have to deal with discipline and playing the 'bad cop' for the first time ever, during a period when they and their children are still hurt and trying to come to terms with their loss."

Simon Valentine, 39, from Cambridge, is one father who found the support of other widows invaluable after losing his wife Karen, in February 2009. "Karen was diagnosed with having inoperable pancreatic cancer just four months after the birth of our second child, Henry. Our daughter Alicia was five. The medical people were quite clear that it wasn't going to get better, that she had at best two years, and that we should 'make provision for the future'. Of course your instinct is to fight it, to remain hopeful. Karen had the constitution of a camel and was strong and determined, but within 18 months of the diagnosis she died."

Like Simon Carr's wife, Karen was treated at home and died there. "Alicia and I were in the bedroom with her when she died. For Alicia that eased the confusion. She understood mummy had gone. But Henry was barely two and could not understand it. We held a party for Karen on her birthday and celebrated her life, and made a card for her and a cake, but Henry still asked when she'd be coming back."

Simon's sister suggested he contact the Way Foundation. "Though, at the time, I didn't really feel like I needed a support group as such. In fact I remember on the day of Karen's funeral, when friends and family were gathered all around us helping look after Henry and Alicia, I thought to myself, 'I'm really lucky to have all these people here – I can't imagine how it would be to try and deal with this on my own.'" But when he registered with the website he found people who shared his sense of loss. "In no time I'd received loads of emails from people telling me they'd been there. It was really, really lovely because these people knew what we were going through as a family, what I was going through as a father."

It's often the anonymity offered by an online support group that provides an outlet for feelings that widowed men and women feel obliged to bottle up. "Society has certain expectations as to how people should grieve," suggests Linsay Black. "But some of the emotions you feel at the time aren't ones you can express to the close friends or family of your dead partner. You can feel very angry towards them for dying and leaving you alone to cope. You could be at your wits end with the reactions of others, struggling to deal with the children, or sometimes you just feel like you want to have someone alongside you – to have sex with someone. You can't say this at the time because it's not what we're 'meant' to be feeling as grieving widows – but it's the way you do feel some days."

Simon Valentine recalls that "you encounter very strange reactions from people who don't know what to do or say to you. One woman was so shocked at the death of Karen and voiced it so adamantly in the street to me that I almost felt I had to apologise. Another woman, when introduced to me, said, 'Oh you're the one with the wife.' I had to laugh and replied, 'I'm the one without a wife, actually.' When I mentioned it to other website members, we'd all had such experiences.

"You also find yourself protecting others from your news," says Simon. "You know it's difficult for people to know what to say to you. I took a tip from someone on the website. Before I returned to work I emailed all my colleagues and said, 'I know you're thinking of me etc, but please don't feel like you have to say anything if you don't want to – just give me a smile.' I had a few people come up and thank me for that."

Sex and the issue of starting new relationships is a subplot in The Boys Are Back. "Widowed men have a tougher time maintaining new relationships," reveals Linsay Black, citing anecdotes from male group members who have struggled to find new partners. "Often it's because men are more likely to look for someone to fill the void, or they're more likely to focus on their own needs and less likely to be concerned about how their children feel about the new woman they're seeing."

According to the Child Bereavement Trust, it's estimated that 20,000 children lose a parent every year and the most recent government statistics suggest there are 36,000 widowed men under the age of 50 in the UK. "Because the data covers only those people who are formally married it's impossible to know the exact number of young men and women raising children alone after the death of their partner," says Linsay Black.

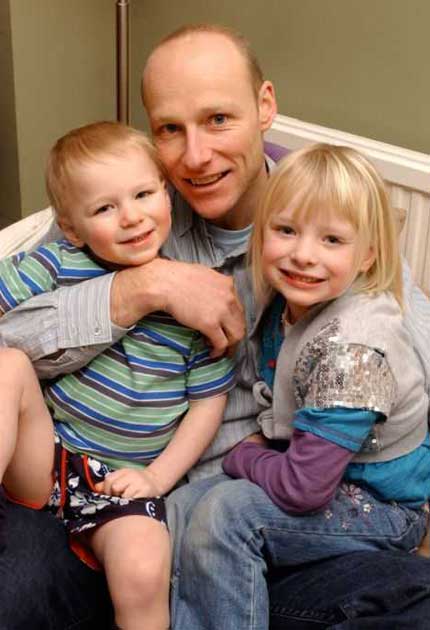

Andy Simmons, 46, from St Albans, feared he'd struggle to cope bringing up two children alone when his wife Angela died from cancer in July 2008. "Although she'd been ill for some time her death came quite suddenly. We never really discussed how I would run the home when she was ill so I wasn't prepared in any way." But the "so what?" approach adopted by Joe Warr in the movie wasn't one Andy followed in caring for Natalie, seven, and Jamie three.

"Admittedly you don't sweat the small stuff so much, but I was determined I wouldn't let things slip," he says. "I tried to establish routines and to keep us all occupied while we were grieving. I accepted every invitation I received to get out of the house and see people. Anything we could do together I would say yes to because I didn't want to be at home with the reminders. But as time went on I realised that the children wanted time with me, alone, and that we needed to find our own way forward."

It's now 18 months since Angela died and Andy believes the support offered by the widows using the support site is now more relevant to him than ever. "Friends do stay in touch, but after a while the calls become fewer and less frequent. People have this idea that the grieving process is over after about a year, that you get over it, but you don't. This Christmas was worse than the last for me because I didn't have the adrenaline I did last year. When the children are asleep I sit back and things can hit quite hard."

Andy has been attending local social events organised by the Way Foundation. "They've been a constant for me and support groups made up of people with shared experience of losing their wife or husband seem to give some normality to things; you can chat and laugh and feel comfortable doing it. It's still hard to know what to do: there are no rules for how widows should be but I have learned to be honest with people. If I'm having a bad time I do tell people, but when I say I'm ok, then I am."

Widowed dads: How to help

* When finding the right words to say doesn't come easily, we opt for saying nothing. "But even 'I'm so sorry, I don't know what to say' is better than avoiding someone who is recently bereaved," insists Linsay Black of the Way Foundation.

* Tell them how you feel. Simply saying 'I miss her, too' is nice to hear. Don't assume that a grieving friend wants to move on and not talk about the loved one they've lost.

* Avoid over-empathising. Phrases such as "I know how you feel" or "You're being so strong" aren't great – and neither is equating your divorce with their loss.

* Put food on the table. In the early days, it's hard to even think of things to cook. You can help by phoning then when you're going to the supermarket and asking if there's anything they need.

* Don't think they'll "get over it". You don't "get over it", you simply learn to live with grief. Remember significant days like birthdays and wedding anniversaries, not just the anniversary of the person's death. Keep in touch – a weekly text, phone call or email is incredibly helpful.

* Make practical offers, too. "When you're still in shock and struggling to organise the basics in life," says Simon Valentine, "everyone says, 'If you need anything, let me know.' But I felt very awkward asking for help, But it's a different matter when someone says: 'On Tuesday after nursery I'm taking your two round to ours for tea, and I'll bring them back at 6.30', or 'I've been shopping and I bought you some frozen meals', etc. These are the people who used to bring tears to my eyes, who took the responsibility away from me and simply did something."

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks