Why conspiracy theories are so popular and how our suspicious minds look for big causes for big outcomes

The speed with which conspiracy theories spread can make them seem typically modern. But, Rob Brotherton, the author of a new study on the mind of the 'truther', says they are as old as thinking itself and tap into our darkest prejudices.

Before the victims had been identified, before any group had claimed responsibility – before the blood had been cleaned from the streets – the “truth” about the terror attacks in Paris was already taking shape online. Just hours after the last shots, one YouTube user explained what had happened in a video that has since been viewed more than 110,000 times.

“It was a false flag event aimed at destabilising Europe into New World Order oblivion,” the anonymous man says in narration laid over shaky mobile phone footage of his laptop. The computer displays images of immigration and the Wikipedia entry for subversion. “Friday 13th is not a coincidence! – it's an occult date of evil Illuminati satanists,” he adds.

As photographs and footage of the attacks emerged, armies of “truthers” went further, describing in dozens of similar videos and on their slick websites how, among other things, the crime scenes had been staged by the intelligence agencies. The fleeing woman filmed dangling from a window at the Bataclan theatre was an actor wearing a harness.

Terror attacks are always fertile ground for conspiracy theories, none more than 9/11, but committed conspiracy theorists find “truth” anywhere. One truther, as conspiracy theorists prefer to be known (many believe that the use of the term “conspiracy theory” is part of a conspiracy theory) was arrested in Connecticut this month after confronting the sister of a teacher who died in the 2012 Sandy Hook school shooting.

“This conspiracy about the photo has really caught on online,” he told the New York Daily News, referring to an old family photo of the teacher and her siblings on rocks by the sea. He believes Sandy Hook never happened, while others think it was another false “flag event” (an old naval term now used to describe secret plots). “People say the rocks don't match up,” he added. “The shadows don't match up.”

“The shadows don't match up” could have been the title for a new book about conspiracy theories. But in Suspicious Minds: Why We Believe Conspiracy Theories, Rob Brotherton seeks not to take on the theories or their creators. Doing so is “like nailing jelly to a wall”, he says, because a defining characteristic of conspiracy theories is that they cannot be proved – they change shape in response to any challenge.

“But it's also a bad way to engage in conversation,” he adds from Barnard College in New York, where he is a psychology professor. “It's more useful to start by looking at what we have in common.” Brotherton, 28, who is originally from Northern Ireland, argues two things: that conspiracy theories are as old as thinking itself; and that we all share the subconscious biases that allow theories of varying degrees of credibility and potential harm to take hold.

“You hear all the time that we're in a golden age of conspiracy theories,” he says. “People blame the internet or even TV shows like The X-Files. But the research shows that's not true. The internet has made it quicker and easier to share theories, but there has always been this background hum of conspiracy. It's a fundamental part of being human.”

Brotherton does not underestimate the harm that many conspiracy theories can cause. He considers the incalculable cost of The Protocols of the Elders of Zion, the fabricated anti-Semitic text that described a plan for Jewish world domination. Published globally in the early 20th century, it directly inspired the Nazis. He also looks at the anti-vaccine movement, comparing current suspicion to identical scares that developed centuries before a disgraced doctor linked MMR to autism. “In the case of violent extremism conspiracy theories can tap into our darkest prejudices,” he writes. “In the case of vaccine anxiety [they] can tap into our desire to protect the people we love the most.”

Theories also invariably tap into a suspicion of authority, informed by examples of conspiracy facts that would have seemed similarly outlandish before they were exposed (look up the Tuskegee Syphilis Study, in which dozens of poor black men were allowed to die as part of a secretive medical study carried out by the US government between 1932 and 1972). The line between healthy scepticism and paranoid delusion is bendy and moving.

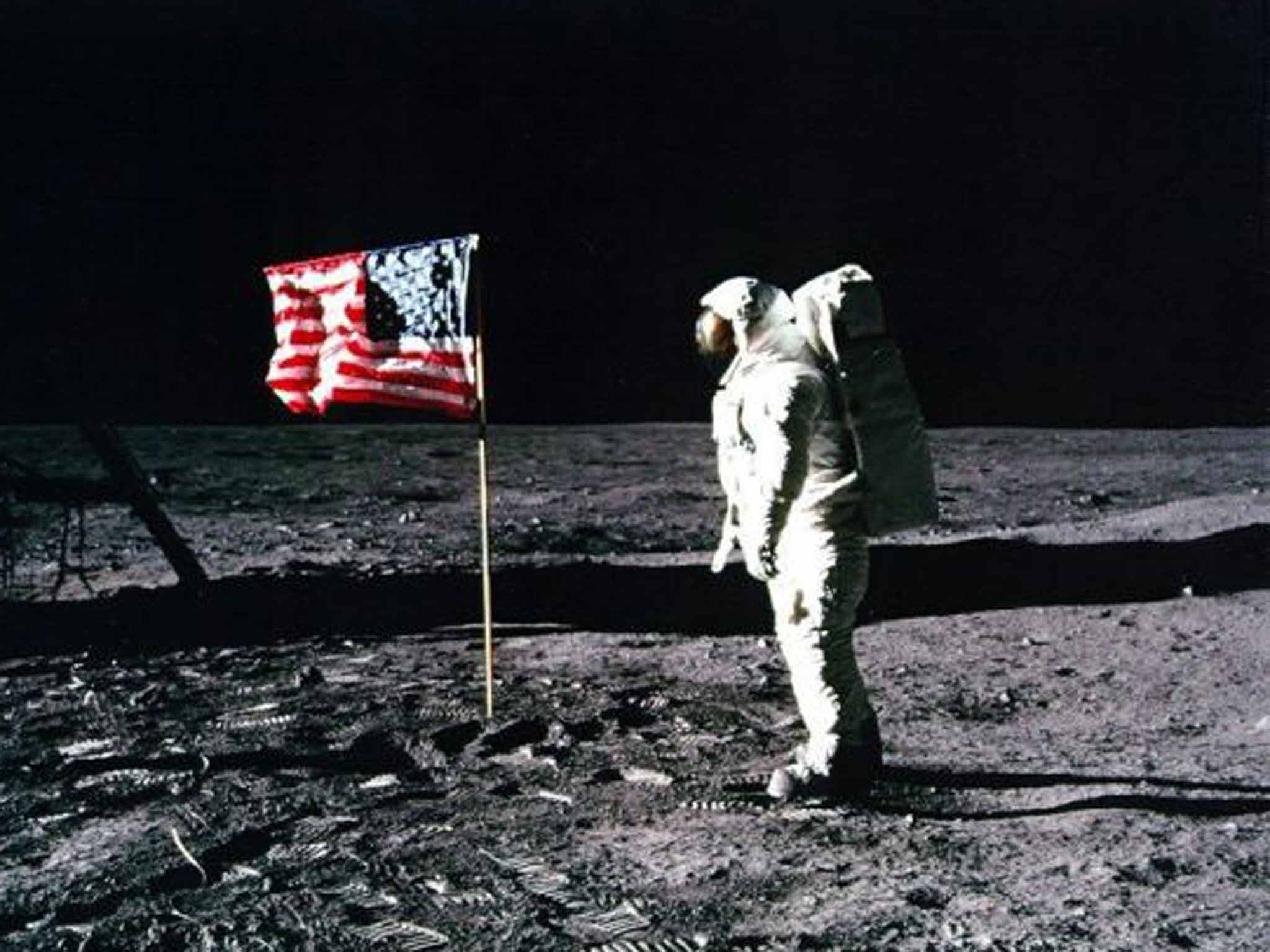

Whether they are harmful or harmless (Elvis is alive; the moon landings were staged) conspiracy theories come from the same, flawed place – our brains. Brotherton starts his book with a description of a simple experiment. One by one, two groups of students at the University of Amsterdam were told to think of something they were ambivalent about, and type out the pros and cons. Each student was then told the computer wasn't working. A supervisor guided them into a smaller room to continue the survey. The students from one group were taken to a messy cubicle and shown an image made up of hundreds of random black splodges, and asked if they could make out anything in them. Students from the other group did the same thing, but were asked to tidy the cubicle first.

Subconsciously, all the students were seeking clarity after considering something they had mixed feelings about. But the students still surrounded by disorder saw almost twice as many phantom images in the random splodges as the group who had tidied up. “Ambivalence threatens our sense of order, so, to compensate, we can seek order elsewhere,” Brotherton writes. For the second group, which imagined fewer images, he adds, “the simple act of tidying the desk – transforming the chaos into order – had already satisfied their craving”.

He goes on to explain the biases in all our brains. The confirmation bias means we favour evidence that supports what we already think. Taken to extremes, it can also lead us to discount or challenge what should be beyond dispute. So President Obama's birth certificate, when he released it, was not evidence that he is American, but of a conspiracy, because “this pixel-by-pixel analysis clearly shows it was forged”.

More powerful still is the proportionality bias, which means we instinctively look for big causes for big outcomes. (In reverse, it explains why we give dice a big shake and a big blow when we want to roll a big number). In one study Brotherton cites, two groups were told about an explosion on an airliner. In a scenario presented to one group, the plane crashed and everyone died. In the other, they survived after an emergency landing. The groups were asked to rate the likelihood of possible causes. The “death” group blamed a terror plot, while the “survive” group thought the same explosion on the same plane was more likely to have been caused by a mechanical fault.

“The idea that on 9/11 a bunch of minimally trained guys could have changed the course of history doesn't ring true according to that bias,” Brotherton says. “Nor does the idea that a lone gunman could have got out of bed and shot JFK. It doesn't fit with our assumptions about the way the world works.” How could Princess Diana, of all people, have died in a simple car accident? How could a tiny pathogen lead to the Aids epidemic? How can humans be descended from swamp animals? How could a gang of deluded young men with guns kill people like us in a city like Paris? “These causes don't live up to the magnitude of their consequences,” Brotherton writes.

Next semester Brotherton will teach a class about conspiracy theory and hopes his books triggers further debate in a relatively new field of research. He wants theories to be challenged when they cause harm, but otherwise to be examined in a way that tells us something about ourselves. “We have innately suspicious minds,” he writes. “We are all natural-born conspiracy theorists.”

'Suspicious Minds' by Rob Brotherton (£16.99, Bloomsbury) is out tomorrow

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies