'No evidence' high street child allergy tests work

Parents of children with suspected food allergies are warned today to avoid high street tests and diagnostic services advertised online which have "no value", according to experts.

Patients can run up bills of hundreds of pounds for commercial allergy tests, including hair analysis, kinesiology and the "Vega" test, which uses a machine to measure electrical impulses passing through the body.

However, guidance from the National Institute for Clinical Excellence (Nice) says there is "very little evidence to show that these tests work" and they are "not recommended". Food allergies among children have seen a dramatic rise with a six-fold increase in hospital admissions in the past 20 years. Six to 8 per cent of children under three are affected, a big leap since the 1990s which remains unexplained.

The Nice guidelines urge wider testing for allergies by GPs while warning parents of the dangers of unproven tests sold by alternative practitioners.

Adam Fox, a consultant paediatric allergist at St Thomas's Hospital, London, and a member of the Nice panel, said: "A whole plethora of alternative testing services has grown up because NHS provision was not great.

"A 2006 survey of patients in our clinic showed 40 per cent had sought complementary diagnosis or treatment. A lot of these outfits advertise a screening test which only costs a few quid in the first instance, but if you test positive – and I suspect most do – you are then offered more tests to establish what it is you are allergic to. They range from the pseudo-scientific to the eclectic and they are completely unregulated.

"The problem was people went to their GP who was sometimes dismissive or didn't know what to do. These guidelines now give GPs an evidence base on what to do."

Allergic reactions to food can be severe and affect the skin, the lungs or the gut. Eating a peanut, for example, can trigger a sudden onset of wheezing. In other cases the reaction may be delayed, such as when eczema is made worse by drinking cow's milk. Treatment is either by avoiding the trigger food, or going through a process of desensitisation where tiny amounts are introduced gradually into the diet to build up tolerance.

Tests show that 6 to 8 per cent of children under three have a genuine food allergy, but up to a third of parents in surveys think their children are allergic. The most common foods to which children are allergic are cow's milk, fish and shellfish, hen's eggs, nuts, wheat, soy and kiwi fruit.

There are several theories to explain the rise in allergies, but none has been proved. They include homes that are too clean, leaving children's immune systems unexposed to bugs (the "hygiene hypothesis"); a lack of vitamin D from the sun, poorer diets, increasing use of paracetamol (usually in Calpol), and delayed weaning (the introduction of solid foods).

Case study: 'He was fine until I started weaning him'

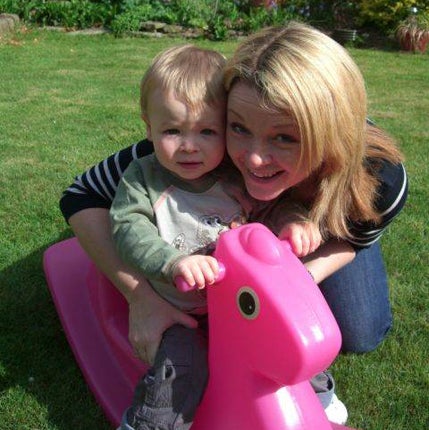

William Farrow, 2

Days after he was born on 5 December 2008, William Farrow came out in a rash. His mother Katherine, 38, didn't know it then but he had a severe allergy to the formula milk with which she was topping up her breast-feeding. "He was covered in eczema, very unhappy and constantly crying. After a week he became listless – he just lay there."

She took him to the GP who sent them straight to Queen's Hospital in Romford, Essex. William was kept in for a week with a suspected virus. After being discharged, Katherine breast-fed him exclusively and the problem disappeared. "He was fine for four months until I started weaning him on to baby rice. He wolfed it down and then vomited, and where the vomit landed his skin bubbled up and started coming off. It was then we realised he must have an allergy."

William was referred to a paediatrician and after a battery of tests was found to be severely allergic to milk, wheat, gluten, soya and eggs. With support from Allergy UK, Katherine was helped to exclude these from his diet. But things got worse. At the age of eight months he went into anaphylactic shock: his eyes and face swelled, he had difficulty breathing and had to be taken to hospital. He had been playing with a toy handled by a toddler who had just eaten eggs.

"They gave him an adrenalin injection as well as steroids and Piriton [an antihistamine] and he was kept in overnight. Now I carry an EpiPen [adrenalin injection] everywhere. It is possible he will grow out of it. That is what we are hoping," she said.

Jeremy Laurance

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies