Scientists hail the first effective treatment for skin cancer victims

'Personalised' drug keeps melanoma at bay for six months, trials demonstrate

Scientists have developed the first "personalised" drug shown to be effective against advanced melanoma, the deadliest type of skin cancer which is on the rise in Britain.

Warnings about the risks of melanoma were heightened this weekend as the fine weather drew thousands to sunbathe outdoors, putting them at increased risk. "Binge tanning", where sunbathers allow their skin to burn in their eagerness to get a tan, is a key cause of the cancer.

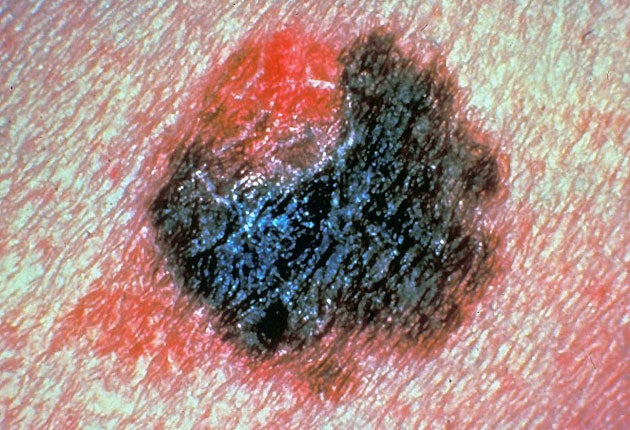

Melanoma, which starts as a blemish or change to a mole on the skin, is treatable in its early stages but once it has spread to other organs such as the lungs and liver there are no treatment options. Patients with melanoma that has spread usually die within months.

In the first trial in human beings of the new drug, known only by its code name PLX4032, those treated lived on average for six months without their disease getting worse. Asked what difference the drug made, one doctor said that for the first time he had "time to get to know my patients".

The drug is the first of half a dozen agents which are in development, designed to target advanced melanomas that are "BRAF positive", meaning they have a specific genetic make-up containing the BRAF mutation.

They are the harbingers of a revolution in cancer medicine which is seeing the development of an increasing number of drugs tailored to the genetic make-up of individual cancers, so treatment can be personalised for each patient, not just determined by the cancer's location or stage.

BRAF is a cancer-causing mutation which is implicated in 60 per cent of melanomas and 8 per cent of other solid cancers. The new drug works by selectively targeting and destroying tumour cells that carry the BRAF gene but it has no effect against melanomas that lack the mutation. It is also being developed for use in other cancers including bowel cancer.

In the Phase 1 trial, half of the 16 patients treated saw their tumours shrink by 30 per cent and survival without disease progression was extended. The results were presented at the American Society for Clinical Oncology meeting in Orlando yesterday.

Keith Flaherty, an assistant professor at the Abramson Cancer Centre of the University of Pennsylvania, who led the trial, said: "Seven years after BRAF mutations were first identified, we have validation that this mutation is a cancer driver and therapeutic target. In addition to a new and important chapter in the story of targeted therapy development in cancer, we are especially excited for our melanoma patients for whom there are few treatment options."

In the UK, the number of people diagnosed with melanoma has risen fourfold since the 1970s and has exceeded 10,000 annually for the first time. The typical victim is the pale-skinned office worker who spends two weeks broiling on a Mediterranean beach until their skin is red and blistered. Covering up in the midday sun and using high-factor sun cream is the best defence against the cancer.

Roche, the Swiss multinational pharmaceutical company, developed the drug with its partner Plexxikon, a biotech company. It is being launched with a diagnostic test to screen patients for the BRAF mutation.

Professor Caroline Springer, the head of the gene targeting team at the Institute of Cancer Research in London, which is developing its own BRAF inhibitor, said the gene mutation was an "excellent target" for drug development: "If melanoma is caught in the early stages it is treatable. Once it has metastasised [spread to other organs] there is nothing. Survival is very low.

"Our agent is very different from [PLX4032]. We intend to trial it at the Royal Marsden Hospital in London. We are optimistic there will be a trial.

"I think Roche are in the lead – they are certainly getting there quite quickly but there is a long way to go. It is obviously very exciting to have a drug whose potential could be very good."

Half a dozen BRAF inhibitors were being prepared for clinical trials but the teams developing them were yet to prove they were safe and effective, Professor Springer said.

Cancer drugs: Why the future is uncertain

Q What is the future for cancer drugs?

A In the past, drugs have been developed to target a specific cancer – breast or lung or bowel – at a certain stage, early or advanced. Now drugs are being developed to target cancers with a specific genetic make-up.

Q What does this mean?

A It means the end of blockbuster drugs that treat everybody and the start of treatment tailored to groups of individuals. An early example is women with Her2-positive breast cancer (a specific genetic type which is more aggressive) who account for a third of all breast cancer cases, and can be treated successfully with Herceptin. For the two-thirds of women with Her2-negative breast cancer, the drug is useless.

Q What are the benefits of this approach?

A Patients avoid the risks – and the side effects – of being treated with drugs that don't work. An important part of cancer treatment is to reduce unnecessary suffering. At the same time it saves the NHS cash because drugs are not wasted on patients who won't benefit. Many cancer drugs cost thousands of pounds per patient.

Q Are there any downsides?

A Yes. If the potential market for a drug is reduced because it is targeted at a narrower patient group, then its price is likely to rise. So a cancer that costs £10,000 a year per patient to treat today could cost £20,000 to £40,000 to treat in the future.The cost will depend on the number of new drugs, the size of each patient group and hence the size of the market for each drug.

Q What is the future for drug research?

A Uncertain – because the more the market is segmented, the greater the uncertainty drug firms will face in recovering their investment from developing new drugs. Cancers with common genetic types that affect a large number of patients – such as BRAF-positive melanoma which accounts for 60 per cent of all melanoma cases – will be more likely to get new treatments.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies