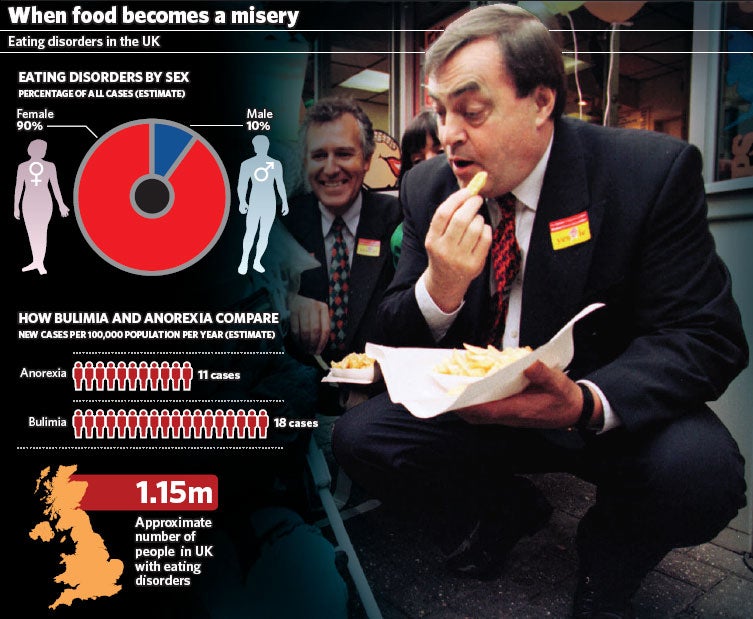

The Big Question: What causes a man like John Prescott to suffer bulimia, and is it dangerous?

Why are we asking this now?

In what must rank as one of the most unexpected revelations of recent years, John Prescott, Labour MP and former deputy prime minister, admitted at the weekend that he had suffered from the eating disorder bulimia. Mr Prescott, 69, wrote in the Sunday Times that he would gorge on burgers, chocolate, fish and chips and Marks & Spencer's trifles, and would sometimes consume a whole tin of Carnation condensed milk. He said the problem dated from his appointment to the shadow Cabinet in the 1980s and continued after Labour came to power in 1997, brought on by stress and long hours of work. "During those years when we first got into power, I let things get on top of me and took refuge in stuffing my face," he said. He had received medical treatment and had no relapses f or "more than a year," he said.

Is what Mr Prescott described genuine bulimia?

There is no reason to think otherwise. Some media reports have been wantonly cruel – highlighting his remark about "stuffing his face" – and poking fun. Others have doubted his motives, noting he has a forthcoming political autobiography to plug. Stephen Glover, writing in the Daily Mail said: "What is intended to pluck our heart strings leaves me pretty cold." But psychiatrists praised his courage and honesty in admitting to a condition that brought shame and embarrassment on him and his family – the very reasons why the problem lies hidden and untreated, often for years.

What causes the condition?

The eating disorders anorexia and bulimia are driven by the desire to be thinner, strongly influenced by social pressures. Teenage girls are the typical victims, but the disorder can also affect boys, who are estimated to account for one in 10 cases, and adults. Anorexia makes itself apparent relatively quickly as victims lose weight, becoming skeletal and ill. Bulimia typically starts with an effort to restrict the diet severely, but this cannot be sustained and ends with a binge, often of the high-fat, sugary foods that have been most avoided. That is followed by vomiting and the cycle begins again. Its origin lies in the normal sense everyone has after a large meal – at Christmas, say – of wanting to cut back next day. But in bulimia the process gets out of control.

Are all bulimics alike?

No. Although the main driver of the condition is a desire to control weight, once the cycle of dieting, bingeing and vomiting is established, each case acquires its own psychological rationale. Mr Prescott attributed his own problem to the stress of his job. According to Colin Brown, The Independent's deputy political editor and biographer of Mr Prescott, the vomiting kept his weight down, despite his eating, but when it stopped his weight ballooned. "That drove him to angst ridden depression which in turn made him eat more."

Is bulimia common in adulthood?

No, at least so far as is known. But it may be that adult sufferers hide it better. One psychiatrist, Ty Glover, of the eating disorders unit at Cheadle Royal Hospital in Cheshire, said he had never come across a man of Mr Prescott's age with it. "It makes me think maybe we are missing a whole audience of middle-aged men who are too scared to admit they have a problem," he said. Ivan Eisler, head of the child and adolescent eating disorders unit at the Maudsley Hospital, south London, said: "It is not very common in later life, but it certainly does exist."

Is it a form of self-harm?

Not exactly. Although it has certain elements in common with the self-harming seen in burning or cutting of the skin – low self-esteem and a sense of dissatisfaction with oneself – there are also key differences. The cycle of dealing with bingeing by vomiting means the struggle to diet is constantly being lost, and that the sufferer is failing to cope. The sense of failure makes victims eat more and vomit again, reinforcing the behaviour. "We all recognise the origins [of trying and failing to control eating] in ourselves. How it builds into something stronger is very individual depending on personal circumstances and personal history," said Dr Eisler.

How dangerous is bulimia?

Sufferers can die from the condition. Overall, eating disorders have the highest death rate of any mental disorder, either by suicide or from the effects of starvation. Anorexia is the main risk, with a death rate among young women sufferers aged between 16 and 25 of around 10 per cent. Bulimia is more common than anorexia, but has a lower death rate. The cycle of bingeing and vomiting is also physically damaging, the main danger being loss of potassium, which is essential to the proper functioning of the heart. If the potassium level drops too low, the heart may give out. Constant vomiting can rupture the oesophagus and damages the teeth, by bathing them in stomach acid. Brushing the teeth makes it worse, because the teeth are being brushed with acid.

Can bulimia be treated?

Yes. Cognitive behaviour therapy, in which patients are taught to break habitual ways of seeing problems by thinking positively, has been shown to be effective. Other types of family or interpersonal therapy aimed at resolving family tensions also help. The biggest problem is getting people into treatment. On average, anorexics take a year before they can be persuaded to seek treatment, but for bulimics it is four to five years. Bulimia is easier to hide. Although Mr Prescott's colleagues suspected he was a compulsive eater, few other than his wife Pauline and some close friends knew he had bulimia, still less that he had been treated for it. Colin Brown, who knows him better than most, spoke for many when he wrote yesterday: "When I first heard about it I found it incredible that a man as robust as Prescott should suffer from an eating disorder."

Will Mr Prescott's confession do more than boost sales of his autobiography?

Undoubtedly. Eating disorder specialists were united yesterday in appreciation of his courage in speaking out. They said the astonishing revelation by the former deputy prime minister would raise awareness of the condition and help other sufferers confront their problem and seek help. Dr Eisler said: "The main reason people keep the condition hidden is because they feel ashamed and think there is nothing that can be done. Actually there is very good and effective treatment. The message we need to get across is that there is help out there and it works."

Should we be worried about the impact of bulimia on middle-aged men?

Yes...

* After John Prescott's confession, psychiatrists fear the condition may be widespread but hidden in adult men

* Sufferers typically put up with the illness for four to five years before seeking help, and may wait as long as 10 years

* Effective treatment is available, but sufferers feel too ashamed to seek it and believe nothing can be done

No...

* Bulimia mainly affects teenage girls and young women aged 16 to 25, in whom the effects may be severe

* Men account for one in 10 of eating disorder sufferers and are mostly in their teens and twenties

* Psychiatrists said yesterday that male sufferers of John Prescott's age were extremely rare

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments