The forgotten 2,000-year-old tradition that keeps you warm in the winter

A practice common across east Asia but largely forgotten in Europe could be key to staying cosy in the cold

On winter mornings in Harbin, where the air outside could freeze your eyelashes, I would wake up on a bed of warm earth.

Harbin, where I grew up, is in northeast China. Winter temperatures regularly dip to -30°C and in January even the warmest days rarely go above -10°C. With about 6 million residents today, Harbin is easily the largest city in the world to experience such consistent cold.

Keeping warm in such temperatures is something I’ve thought about all my life. Long before electric air conditioning and district heating, people in the region survived harsh winters using methods entirely different from the radiators and gas boilers that dominate European homes today.

Now, as a researcher in architecture and construction at a British university, I’m struck by how much we can learn from those traditional systems in the UK.

Energy bills are still too high, and millions are struggling to heat their homes, while climate change is expected to make winters more volatile. We need efficient, low-energy ways to stay warm that don’t rely on heating an entire home with fossil fuels.

Some of the answers may lie in the methods I grew up with.

A warm bed made of earth

My earliest memories of winter involve waking up on a “kang” – a heated platform-bed made of earth bricks that has been used in northern China for at least 2,000 years. The kang is less a piece of furniture and more a part of the building itself: a thick, raised slab connected to the family stove in the kitchen. When the stove is lit for cooking, hot air travels through passages running beneath the kang, warming its entire mass.

To a child, the kang felt magical: a warm, radiant surface that stayed hot all night long. But as an adult – and now an academic expert – I can appreciate what a remarkably efficient piece of engineering it is.

Unlike central heating, which works by warming the air in every room, only the kang (that is, the bed surface) is heated. The room itself may be cold, but people warm themselves by laying or sitting on the platform with thick blankets. Once warmed, its hundreds of kilograms of compacted earth slowly release heat over many hours. There are no radiators, no need for any pumps, and no unnecessary heating of empty rooms. And since much of the initial heat was generated by fires we’d need for cooking anyway, we saved on fuel.

Maintaining the kang was a family undertaking. My father – a secondary school Chinese literature teacher, not an engineer – became an expert at constructing the kang. Carefully building layers of coal around the fire to keep it alive over the night would be my mum’s job. Looking back, I realise how much skill and labour was involved, and how much trust families placed in a system that required good ventilation to avoid carbon monoxide risks.

But for all its drawbacks, the kang delivered something modern heating systems still struggle to deliver: long-lasting warmth with very little fuel.

Similar approaches across East Asia

Across East Asia, approaches to keeping warm in cold weather evolved around similar principles: keep heat close to the body, and heat only the spaces that matter.

About the author

Yangang Xing is an Associate Professor in the School of Architecture Design and the Built Environment at Nottingham Trent University.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

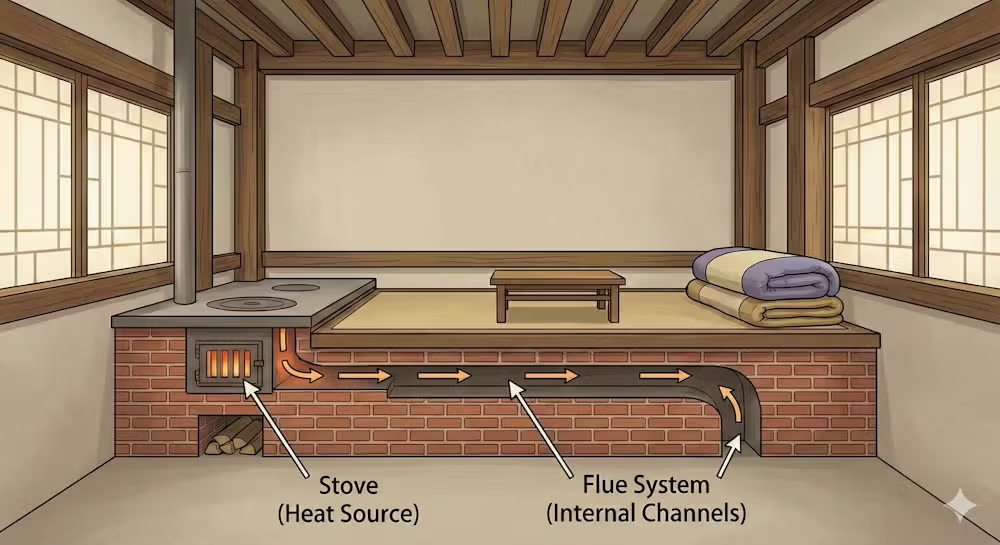

In Korea, the ancient ondol system also channels warm air beneath thick floors, turning the entire floor into a heated surface. Japan developed the kotatsu, a low table covered by a heavy blanket with a small heater underneath to keep your legs warm. They can be a bit costly, but they’re one of the most popular items in Japanese homes.

Clothing was also very important. Each winter my mum would make me a brand new thick padded coat, stuffing it with newly fluffed cotton. It’s one of my loveliest memories.

Europe had similar ideas – then forgot them

Europe once had similar approaches to heating. Ancient Romans heated buildings using hypocausts, for instance, which circulated hot air under floors. Medieval households hung heavy tapestries on walls to reduce drafts, and many cultures used soft cushions, heated rugs or enclosed sleeping areas to conserve warmth.

The spread of modern central heating in the 20th century replaced these approaches with a more energy-intensive pattern: heating entire buildings to a uniform temperature, even when only one person is home. When energy was cheap, this model worked, even despite most European homes (especially those in the UK) being poorly insulated by global standards.

But now that energy is expensive again, tens of millions of Europeans are unable to keep their homes adequately warm. New technologies like heat pumps and renewable energy will help – but they work best when the buildings they heat are already efficient, allowing for lower set point for heating, and higher set points for cooling.

This highlights why traditional approaches to warming homes still have something to teach us. The kang and similar systems show that comfort doesn’t always come from consuming more energy – but from designing warmth more intelligently.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks