Direct from the trenches: The objects that defined the First World War

Peter Doyle reveals fascinating details about the Great War in an extract from his book 'The First World War in 100 Objects'

From the leather football that led the London Irish Rifles’ fearless charge over the top, to the chivalrous air ace who sought out his enemy's hand after shooting him from the sky, the Great War left us with a legion of extraordinary tales that still resonate a century on...

Trench coat

Country of origin: United Kingdom

Date of manufacture: c.1917

As we know it today, the trench coat is very much a fashion statement. Stylish and unisex, it has been seen in all cuts and colours. Not surprisingly, its military antecedents were more commonly light khaki in shade – attempting to blend into the background of the battlefield – and were born out of the practical necessity of providing protection to the wearer who, more often than not, would be occupying a hole in the ground open to the elements.

The standard cold-weather protection issued to soldiers was the greatcoat, or capote in France. Constructed from wool serge, they were a considerable weight, even when dry. Difficult to wear with equipment, and prone to fouling with mud and water – creating an even weightier piece of clothing – they were bulky and long.

Trench coats were thus in growing demand from soldiers, and the garment on page 14 is typical. Made by London outfitters Thresher & Glennie, it was the property of a lieutenant in the King's Own Yorkshire Light Infantry, who bought it in 1917 and adorned it with rank badges and formation signs. Its principal features align with the best of its type, all focused on "trench use": that it should be made of heavy-duty waterproofed gabardine material (and should be capable of hosting a warmer button-in liner), and that it should not be too long so as to be obstructive. We know from contemporary adverts that the coat cost £4 14s 6d.

It is double-breasted, too, with a storm-flap whose purpose was to keep out the cold and wet (which in its descendants is now little more than a vestige). Belts at the waist and wrists provide means of closing off the coat from the elements, while at the throat an additional buttoned throat strap gives the chance to cinch the collars together – thereby resisting both the elements and the unwanted attentions of a gas attack, with gas hoods being tucked into outer garments to provide a more effective seal.

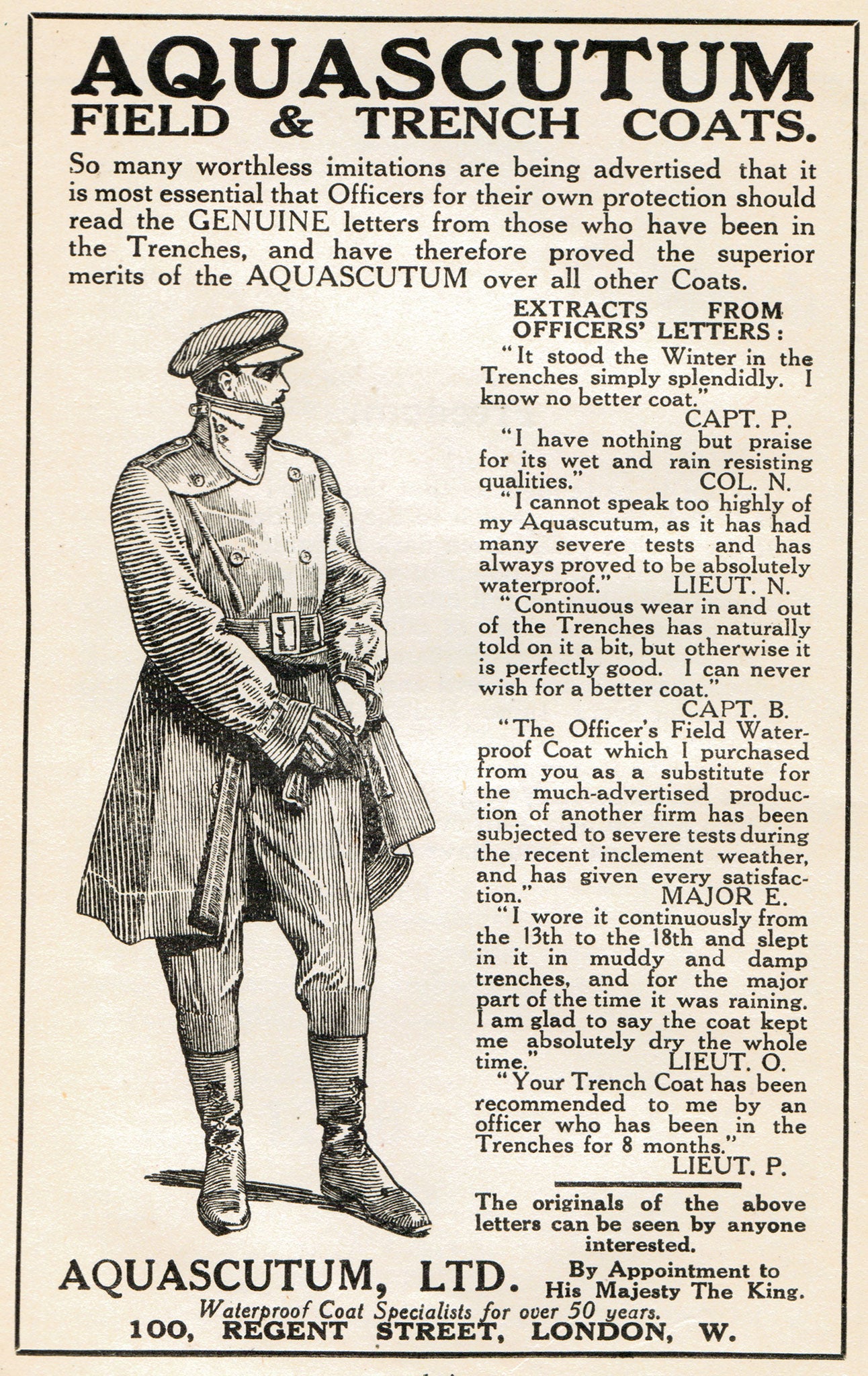

Outfitters from Burberry to Aquascutum (pictured above) offered their own versions, and tempted officers with the chance of owning a piece of kit that was de rigueur. A real example of a military necessity with a direct impact on modern life.

Pickelhaube

Country of origin: Germany

Date of manufacture: c.1915

In 1914, all armies were equipped with some form of uniform cap or ceremonial helmet, but it is perhaps the German helm mit spitze, popularly known as the pickelhaube, that is the pre-eminent example of the type: gaudy, impractical and affording little protection from either the elements or shell fragments and bullets, this headdress was adopted in 1842, reputedly the design of Friedrich Wilhelm IV of Prussia.

The basic component of the German 1895-pattern pickelhaube was a glossy, hardened-leather helmet shell, covered with layers of lacquer for a high shine, with leather front peak and neck guard sewn on. The shell was then furnished with bright brass fittings, the spike complete with ventilation holes. Artillerymen wore a ball representing the cannonball. Both had a mostly ceremonial leather chinstrap and a pair of cockades sporting the national and state colours. To protect it, and reduce its visibility, a cloth cover was created for field use. All in all, the helmet was expensive to make, complex and used many important war materials. In an army that grew rapidly, its production was unsustainable.

The example above is Prussian, of a type first issued in June 1915. Gone were the shiny brass fittings, a metal much in demand to serve the munitions industry. In their place were oxidised steel fittings – cheaper to produce and less visible. The helmet spike was also removable.

On the front line, the pickelhaube was the natural target of souvenir hunters, and there are countless photographs of British soldiers "larking about" in "Hunnish" headgear.

Its alien appearance also made it the target of Allied propaganda, and the helmet appeared in images intended to invoke national hatred: the spiked headgear was worn by snarling beasts, inhuman ravishers of women and despoilers of Europe's cultural heritage. It was destined to be replaced in 1916 by the steel helmet, and with it, fatalities from head wounds declined dramatically. With the passing of the pickelhaube came the birth of industrialised warfare; there was little room for the ceremonial in the killing fields of Flanders, Artois or the Argonne.

Propaganda Cross

Country of origin: United Kingdom

Date of manufacture: c.1914–15

In 1914, as the invading German Army swept through Belgium and northern France en route to encircle Paris, any suspected acts of "terrorism" were dealt with severely. Where shots had been heard from buildings – or had been suspected as such – occupants were taken out and summarily executed, their homes burnt. In all, it is estimated that 6,000 Belgian civilians were killed and some 25,000 buildings destroyed. Notable cultural centres were bombarded in northern France, too; at Reims and Amiens, the great gothic cathedrals were bombarded and badly damaged.

In the wake of these actions, the Allied propaganda machine moved into gear. The crimes perpetrated by the Germans were presented as inhuman acts of savagery against the innocent. Lurid tales of murder, mutilation and sexual depravity were commonplace, and the invasion of Belgium was transformed into the "Rape of Belgium". For the British, the opportunity to castigate the Germans as the "Hun" ravaging Europe was too much.

One output was the production of cast-iron propaganda "Iron Crosses". With both iron and the Iron Cross symbolising purity and chivalry within German culture, it was inevitable that this medal would be selected as a means of ridiculing the enemy. The most common examples, like that illustrated, depict the cross with the words "For Kultur". Kultur was a concept of German supremacy in the arts and other high ideals of Western civilisation. It was not surprising that the Allied propagandists quickly seized on this and depicted jack-booted madmen striding across Europe, all "For Kultur".

Some of the crosses simply state, in heavily ironic overtones, "For Brave Deeds", while others list the cultural sites damaged by the invasion: Leuven, Reims, Amiens. Later additions, like the other example pictured here, even reflect on the naval bombardment of the north-eastern coast of England in late 1914. Who produced the crosses is unknown; perhaps Gordon Selfridge, later responsible for reproducing the Lusitania medal, which satirised the German sinking of the Cunard ocean liner.

The Loos football

Country of origin: United Kingdom

Date of manufacture: c.1915

The Battle of Loos, fought in September 1915, was the largest British offensive on the Western Front. Yet neither the British commander-in-chief, Sir John French, nor the general in charge of the attack, Sir Douglas Haig, wanted to fight there: the ground was poor and the strength of the German positions – holed up in fortified mining villages and slag heaps – just too great. Yet with the Allied strategic situation in a parlous state and the Russians on the point of collapse, the need to support the French was recognised by the British secretary of state, Field Marshal Lord Kitchener. The British commanders had little choice but to attack where their line met that of their allies, just to the north of Lens.

The men of the London Irish Rifles, at the left of the 47th Division line, would be first out of the trenches. The battalion was famous for footballing prowess, its team roundly beating others of the brigade, so it was perhaps not surprising that their entry into the "great push" would involve kicking leather footballs towards the German trenches.

While this was officially frowned upon, one man, Private Edwards, would nevertheless carry a deflated ball into the line; inflating it before zero hour, he would launch the ball with a goalkeeper's throw, punting it towards the line while his colleagues followed it up.

The London Irish would soon drive the Germans from the line. The football had reached its objective; hanging on the German wire, it would eventually find its way back home to the regimental depot.

The Man of Loos is a bronze statue on the war memorial of the London Irish Rifles, depicting a soldier in 1915 garb, holding a football. More remarkable is the preservation of the ball itself. Last seen as a deflated leather bag on the German wire, it survived to become a celebrated relic of the Rifles' involvement in the battle.

Recently restored, the football was revered at post-war mess dinners and regimental events. Yet despite the celebrated nature of this exploit, it has been overshadowed by the same motivational use of footballs by, for example, the East Surrey Regiment at the opening of the Battle of the Somme in July 1916.

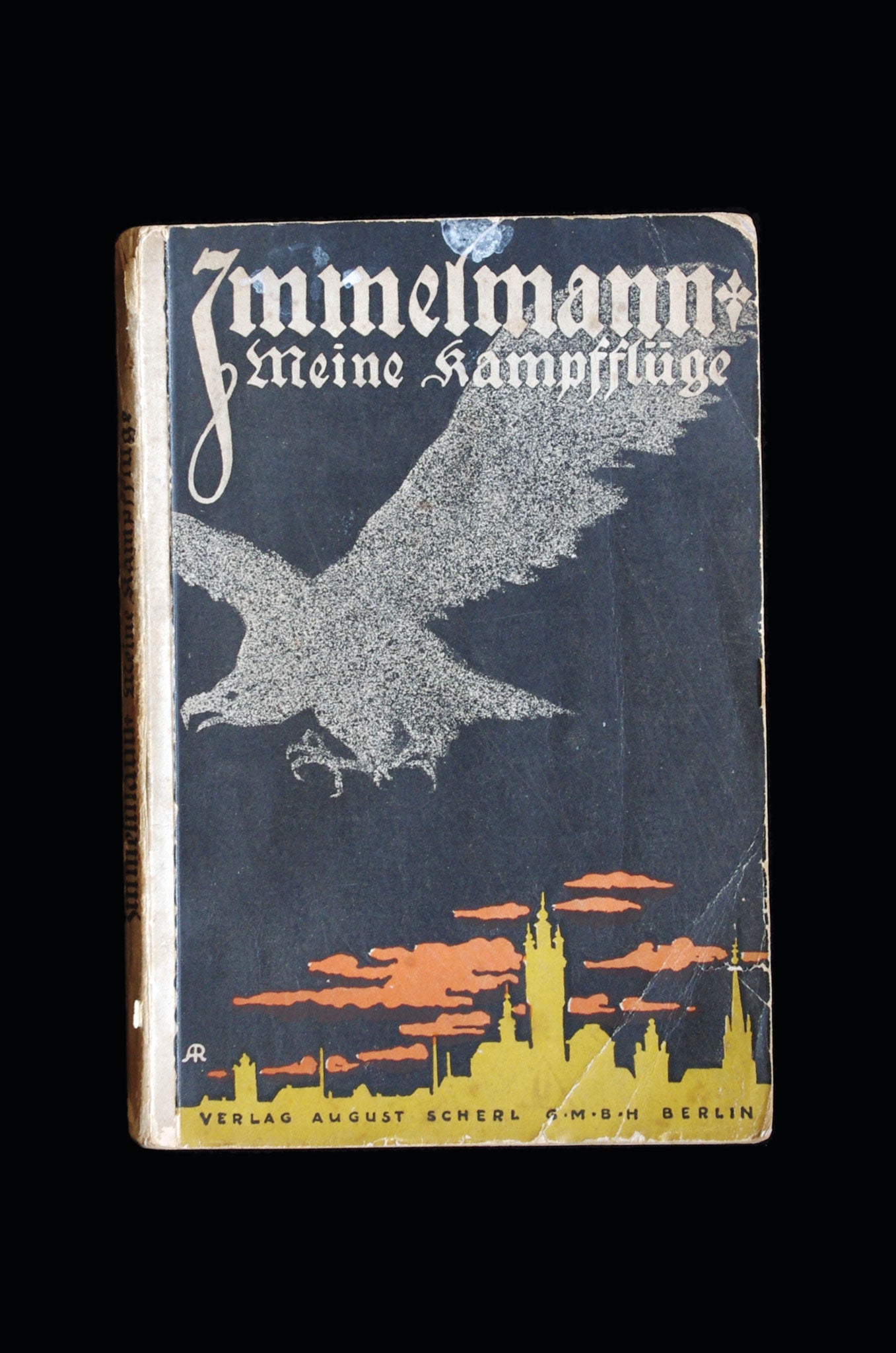

Immelmann: Meine Kampfflüge

Country of origin: Germany

Date of printing: 1917

The cult of the fighter ace was popular in the war and was followed by most nations, the heroic exploits of these airmen an antidote to the dull grind of trench warfare. Max Immelmann was one of the first, and his book, Immelmann, Meine Kampfflüge (My Combat Flights) was published in 1917, a year after his death, containing a view of the famous airman as reflected in his letters home. The strong visual imagery of the German eagle flying over the city of Lille in silhouette is typical of German poster design from the war.

Immelmann's fortunes soared in the summer of 1915, when Anthony Fokker delivered two fighter monoplanes to his squadron. Equipped with an interrupter gear that prevented the forward-facing machine guns from destroying the propeller, it allowed the German ace to aim the whole aircraft at its target.

He described his first aerial victory, against Lieutenant William Reid of the RFC thus: "I tried to keep my machine above my opponent's, because no biplane can shoot straight up. After firing 450 to 500 shots in the course of a flight which lasted 8 to 10 minutes, I saw the enemy go down in a steep glide. When I saw him land, I went down beside him. I went up to him, I shook hands and said: 'Bon Jour, monsieur.' But he answered in English."

The statement encapsulates a sense of chivalry that allowed the public to escape the drudgery of the war. Immelmann was responsible for another 16 combat successes before his death. The "Fokker scourge" was eventually answered by British aircraft with an unrivalled field of view – "pusher" aircraft such as the de Havilland DH2, which featured a propellor behind the pilot's cockpit.

Immelmann died on 18 June 1916 while attacking British "pushers", his Fokker destroyed in the air. Whether it was by artillery, the bullets of his foes – or even from his own, malfunctioning interrupter gear, is difficult to ascertain, but his reputation as a fighter tactician lives on today through the "Immelmann turn" – a simultaneous loop and roll that allows pilots to both evade and attack pursuing aircraft. But his loss was more than the death of a pilot: Immelmann's passing marked the move away from aerial chivalry to the melee of dog fights.

Tank mask

Country of origin: United Kingdom

Date of manufacture: c.1915–18

The tank, a British invention of 1915, was designed to cross trenches of at least 8ft 6in wide (and climb obstacles of 4ft 6in high), thereby puncturing the German lines.

Its characteristic rhombic shape was designed to give as great a surface area as possible to the tracks in order that they might both cross open trenches and climb gradients. The Mark I was deployed for the first time in the latter stages of the Somme.

The tank was to evolve during the war, increasing its reliability, the Mark IV being the main battle tank of the later war period. It was to be deployed in two basic forms, with 6in guns and with Lewis or Hotchkiss machine guns arming their sidemounted sponsons. Both forms, travelling at an average speed of 4 miles per hour, would be vulnerable to shell fire

Each tank had a crew of eight: commander and driver, two gunners and four men to command the complex gears that were required to drive what was essentially a steel box.

The tanks were hot, crowded and dangerous, with plenty of protruding metalwork that could lead to a man knocking himself unconscious in action. To combat this, tank crews were issued with leather helmets to protect their cranium, and chain-mail masks to protect their faces and eyes. The mask was tied around the face, the metal and leather visor bent into position to protect the eyes and nose, and the chain mail hanging from it to protect the cheeks and face.

The purpose of the mask was to prevent shards of metal flying into the face, these shards being an inevitable consequence of bullet strikes on the outside of the tank leading to the spalling of hot metal "splash" inside the tank.

Neither the helmet nor the mask were particularly welcomed by the crews: wearing them must have been uncomfortable in the hot, cramped compartment. Though the use of the mask lingered on, the helmet was abandoned early on: its shape was rather too close for comfort to the German stahlhelm.

This is an edited extract from 'The First World War in 100 Objects' by Peter Doyle (£25, The History Press)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks