My life as a Jew in wartime Berlin: How I outwitted the Gestapo

Marie Jalowicz Simon was 11 years old when Hitler came to power, early in 1933. Some 400 Nazi decrees later, her friends and family were being transported from Germany; and by May 1943, Berlin was declared Judenrein – clear and cleansed of its Jews...

But Marie Jalowicz was still there – among the 1,700 of her people who were able to go to ground, remain in the heart of the Reich and survive the war. She was one of the Untergetaucht – the submerged, also known as 'U-boats'. In this extract from Marie's remarkable memoir, she describes the morning that she managed to outwit the Gestapo.

Early in June 1942, I met Frau Nossek in the street. In the old days we always used to see this simple-minded household help, who worked for my parents, in the Old Synagogue on religious festivals. She always sat in one of the cheapest places in the second women's gallery. After the service she would come over to us out in the yard to shake hands with everyone and wish us well.

Now Frau Nossek told me that she had already received her deportation order, and had been duly picked up with her rucksack and her bundle of bed linen. At the railway station, however, she had suffered such a bad attack of diarrhoea – which she described in all its embarrassing detail – that she had to go to the toilet. When she finally came out again ("such bad luck"), the train had left.

So then, she told me, she had gone over to a railwayman and described her situation, whereupon he had run after the two Gestapo officers who were just leaving the platform and fetched them back.

"Those two gentlemen from the Gestapo were ever so nice," she went on. They had been kind enough to take her back to the place where she had been living and unseal the door of her room, she said, and now she was waiting to be deported in line with regulations a week later.

Later, I was on my way to see my friend Irene Scherhey and her mother, and I told them this story, which was weighing on my mind. "Drunks, small children and the simple-minded have a special guardian angel," was Selma Scherhey's comment. It set off a strange idea in my mind, an idea that was to prove useful: if you pretended to be simple-minded, a guardian angel would come to your aid.

Another incident also influenced me at this time. A family friend, Frau Koch, knew a clairvoyant through a laundry customer of hers. This woman practised her craft in Grünau once a week, although such things were strictly forbidden at the time. Hannchen Koch had a weak spot for mysticism and magic of that kind, and had insisted that we must both go.

I assume that this Frau Klemmstein, who allegedly didn't know who I was, had some idea in advance of my particularly dangerous situation. In any case, she told me, "No one can pretend to a person like you. I don't need cards or a crystal ball. We'll just sit quietly together and close our eyes. Either I'll make contact with you and have a vision, or I won't. If I don't, I'll say so honestly, and Frau Koch will get her money back. And if I do, I'll tell you what I saw."

After we had been sitting in silence for a while, she said, "I see. I see two people, with a Schein." [Translator's note: the German noun has three distinct meanings: brightness, appearance, and a piece of paper.] I thought: "She's crazy." I took her to mean a bright halo such as saints are shown wearing. However, I had mistaken her meaning; she meant a paper document, and more specifically an arrest warrant.

"These men, or one of them, will tell you to go with him. If you do, you are going to certain death. But if you don't – even if you get away by jumping off the top of a church tower – you will arrive at the bottom of it safe and sound, and you will live. When that moment comes, you will hear my voice."

A short time later, a man with an arrest warrant did indeed turn up. As it happened, I was not on top of a church tower but in my room. It was 22 June 1942, and the doorbell rang at six in the morning. In the Germany of those days, that was not the milkman arriving. There was no one who didn't fear a man who came to the door at 6am.

He was in civilian clothes. My landlady Frau Jacobsohn opened the door to him, and he said he must speak to me. I was still asleep, but woke in a terrible fright when I saw him standing beside my bed. In a calm and friendly tone he told me, "Get dressed and ready to go out. We want to ask you some questions. It won't take long, and you'll be back in a couple of hours." That was the kind of thing they always said to prevent people from falling into a fit of hysterics, or swallowing a poison capsule, or doing anything else that would have been inconvenient for the Gestapo.

At that moment, I really did hear the clairvoyant's voice in my room – loud and clear – and as if automatically, I concentrated on the plan I had already hatched: I wouldn't go with him, I would pretend to be half-witted.

Making out that I believed the man, I assumed a silly grin and asked, lapsing into a Berlin accent, "But questions like that, they could take hours, couldn't they?"

"Yes, they could take some time," he agreed.

"But I got nothing to eat here. Now my neighbour downstairs, she'll always have coffee or suchlike on the stove, and I reckon she'd lend me a bit of bread. Can I get a bite to eat? I mean, like this in my petticoat – no one sees me this time of day, and I can't run away from you dressed just in a petticoat, can I?"

So I went out. The only thing I unobtrusively snatched up was my handbag, with my purse in it, and an empty soda water bottle. I knew that they always came in pairs to take people away. And if the second man was waiting for me downstairs, either the bottle or his head would be broken. I wasn't going to do as they told me without defending myself.

When I left the apartment, I saw my landlady turn white as a sheet, but she invited the first man into her kitchen and said, "Come and sit down; it'll take some time for her downstairs to make a sandwich." She steered him over to a chair and moved the kitchen table in front of it, so that he was more or less penned in.

The second man was waiting down in the front hall of the building. I spontaneously switched the role I was playing. "Well, guess what?" I said, giving him the glad eye. "I come out to polish my door knob before I go to work, and my little boy, he's only two-and-a-half, he slams the door on me! So now I got to get the spare key from the mother-in-law, and me in my petticoat, and here's a fellow as I guess wants a bit of the other! At this time of day, too! I never heard the like of it! Men, I ask you!" And so on.

He laughed uproariously, gave me a little slap on the behind, and thought that my conclusion about what he wanted was very funny.

"Well, there's no one going to see me like this," I said. "I'll be back in five minutes."

It cost me a great effort to walk slowly to the next street corner. Then I ran. I spoke to the first person I met, an elderly labourer, briefly explaining my predicament. "Here, come into the entrance of this building," he said, "and I'll lend you my windcheater. You're small, I'm tall, I bet it'll come down over your knees. Then we'll both go to people you know who can lend you clothes." He seemed positively pleased. "And if I'm late to work, who cares? It'll be worth it to put one over on those bastards for a change!"

My hair was loose, lying over my shoulders. He tied it up with a piece of string and escorted me to the Wolff family's apartment. At the time, my lover Ernst was living in Neue Königstrasse with his parents, his aunt and his younger sister, the art historian Thea Wolff. His father was already over 80, so Ernst was the real head of the family. His female relations were indignant about his beginning a relationship with a much younger girl when he was in charge of everything and made decisions for the family. They couldn't stand me, anyway.

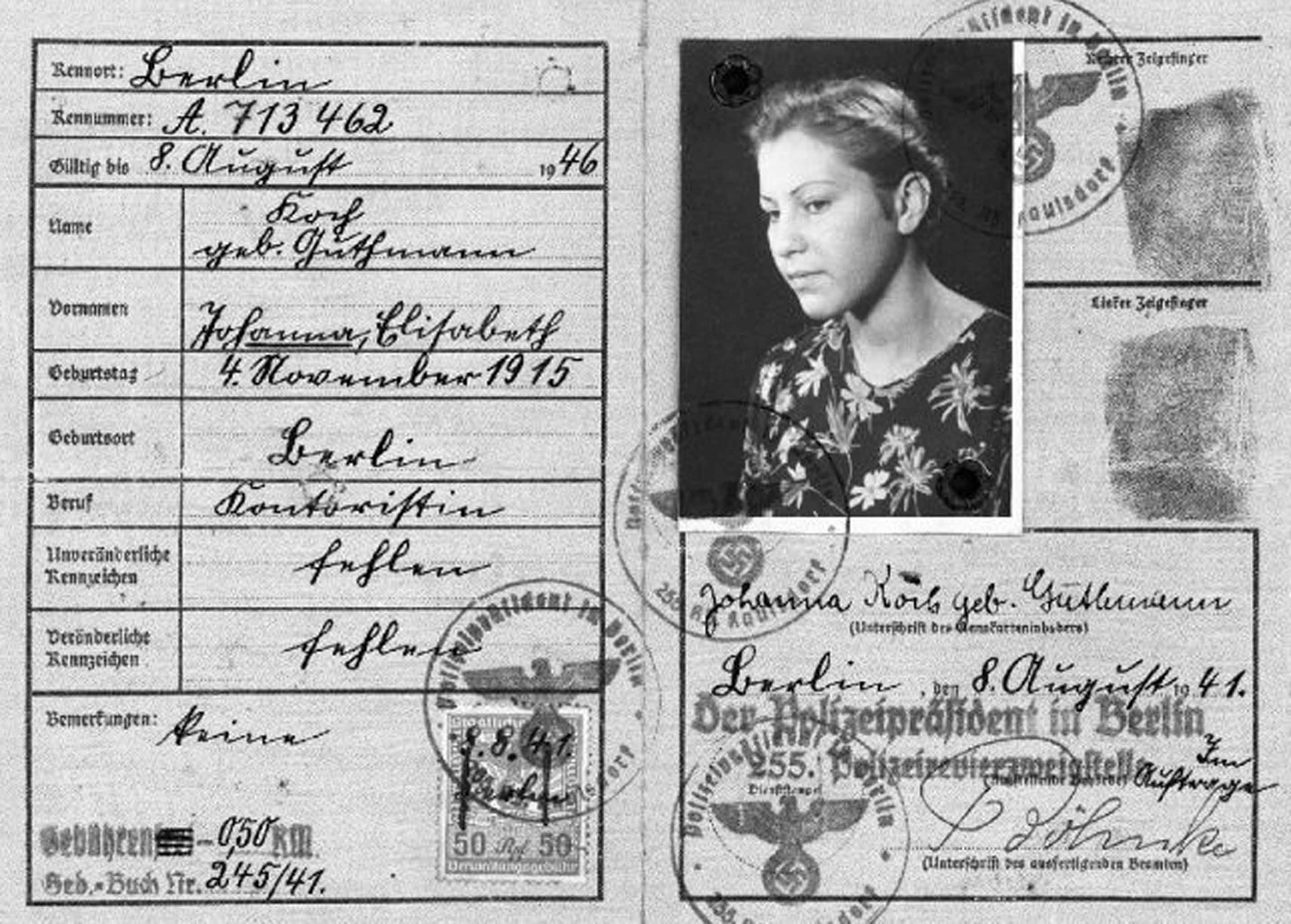

But now they helped me at once. Thea Wolff gave me a summer dress in which I could venture out on the streets again. Apart from that, I had almost nothing left: a few pfennigs in my purse, and my Jewish identity card. For now, I kept the empty bottle.

Later, by devious routes, I got back in touch with the Jacobsohns and found out that my landlady had kept the Gestapo man engaged in conversation for a whole hour, even getting around to the silly delaying tactic of showing him family photographs. And I truly revere the generosity of Frau Jacobsohn, a modest soul who had moved from the provinces to Berlin. She knew that she, her husband and their children would not be able to escape; but even taking that into account, she was ready to accept that they could all be murdered a few months early, so that she could give me a head-start on my pursuers.

I also discovered how it had turned out. After more than an hour, the second Gestapo man had come upstairs and asked his colleague, "Are you two nearly finished?"

When both men realised what had happened there was a frightful row. Each of them was blaming the other, until Frau Jacobsohn told them: "Gentlemen, I can tell you that you've wasted an hour here for nothing. That young woman, my sub-tenant, isn't the respectable sort. She often doesn't come back all night. I'm afraid you've drawn a blank."

But each of them was so mortally frightened of the other that they couldn't agree on that version of events. Instead, they were stupid enough to tell the truth. Frau Jacobsohn was asked to go and see the Gestapo, and found herself confronted by the two men, whose faces had been beaten black and blue.

"Do you know these two gentlemen?" she was asked.

"They look very different now," my landlady said in reply.

One of the pair said, "If we'd known a young girl like that was such a tough nut to crack, we would have surrounded the whole block with police officers."

On that occasion, Frau Jacobsohn was allowed to go home unharmed. But the following year, along with her whole family, she was deported and murdered.

This is an edited extract from 'Gone to Ground: A Young Woman's Extraordinary Tale of Survival in Nazi Germany' by Marie Jalowicz Simon (Profile £14.99), out now

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies