Let's call a truce in the battle of the sexes

Stop bleating on about Mars and Venus, says Men's Hour presenter Tim Samuels – the harsh realities of modern life mean that men and women are becoming more and more alike...

A male clownfish is swimming around minding his own business: keeping an eye out for a hostile stingray, maybe musing on the excellent symbiotic relationship it has with the tentacled anemone it hangs out with, puffed up with pride that Pixar chose to base Finding Nemo on his species. But our fish feels a stirring in his loins. The gonad wall starts to invaginate, ovarian tissue develops, and within a couple of weeks the testicular region has become small and non-functional. Nemo finds he's female.

Fear not. This is not an over-egged metaphor about the state of modern man. Our testicles are still decidedly functional, despite attempts to grow sperm in a lab in Newcastle. And size-wise, we are still putting gorillas to shame. What the clownfish, and his redundant fish-hood, reminds us is that nature has a more fluid approach to gender. Indeed, there'd be little point taking the gender wars into the ocean. Our Nemonic friend only went through a spot of sequential hermaphroditism because the female who dominated the group had swum off or died. Her leaving triggered his sex change – to step into her shoes. Elsewhere under water, the traffic swims the other way – with many a female fish ending its life as a chap.

Fascinating sub-GCSE-biology stuff. And which I tenuously cite because it's my sense that a drop of the aquatic life has made its way ashore. Men and women are becoming increasingly similar in terms of attitudes and actions. What can now be truly classified as distinctly 'male' or 'female' behaviour? If I was spending my late Friday nights chin-stroking on The Review Show, I'd try to get away with referring to this as cultural and behavioural hermaphroditism. I'd probably leave the fish bit out.

Why should an aspirational young man and woman – say, in their twenties – see life any differently during any given day? They'll wake up with their heads equally pumped full of unrealistic expectations for what life has to offer them in today's climate. At work there will be role models of both genders, quite possibly reinforcing how they were brought up. During the day, they'll have similar worries around status, ambition and maybe bread intake. They'll both be socially and financially independent-ish. And have supportive parents to call in the evening who will encourage them that nothing is beyond their reach. Should they be going out on a date that night, our young man and woman are both likely to have trimmed in the pubic region – and neither will want to appear too eager. Before flopping down in front of the same TV boxset and heading to bed for another day on the treadmill. How much ambition and opportunity figured during that day was not dictated by gender, but by the socio-economic hand they'd been dealt. Can you really say that a young woman with a decent education and decent parents will navigate life less smoothly than a young guy lacking such solid foundations?

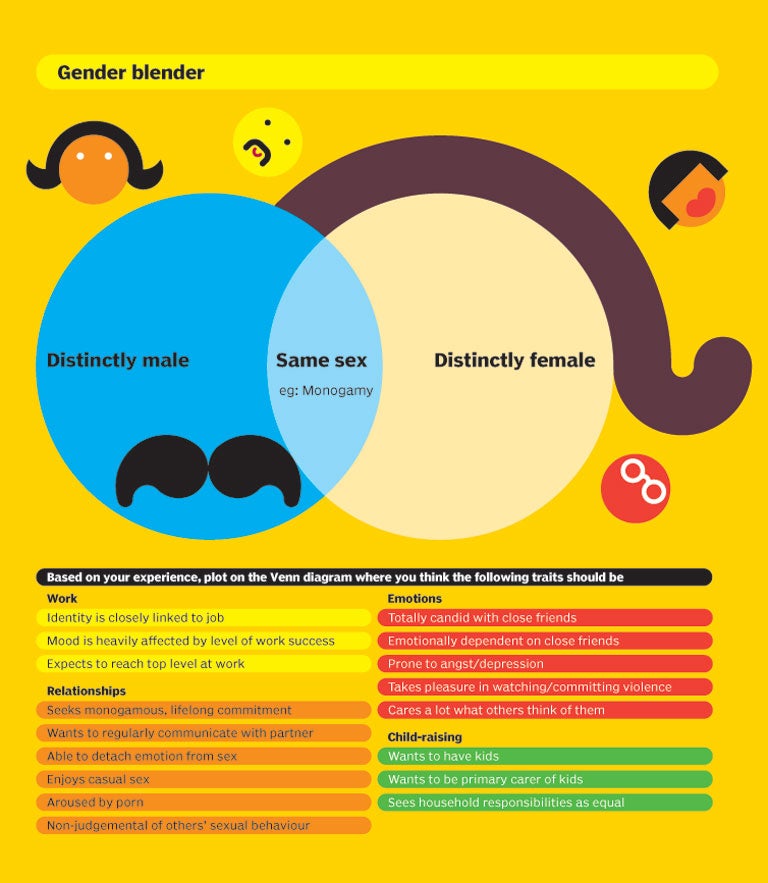

I was intrigued to know whether there was any currency in the notion that men and women are becoming increasingly alike in how we think and act. So having co-opted GCSE biology in pursuit of gender inquiry, the maths textbooks got a dusting off: welcome back the Venn diagram. Two overlapping circles, where the left represents distinctly male traits, the right distinctly female, and the overlap 'same sex' – applicable to both genders. I then drew up a list of 17 traits covering identity, work, relationships, sexual attitudes, friendships, angst, child-raising and violence – and asked a cross-section of friends and colleagues of both genders to plot where they thought those characteristics should appear on the diagram. They were plotting subjectively: based on their experience and that of those around them would they say, for example, that having your identity closely tied your job is a male/female/same-sex trait? Where would they plot the ability to detach emotion from sex? The urge to be the primary carer of kids? Subjective indeed. But perhaps the start of a dialogue, which you can play along with using the Venn diagram printed on the previous page of this article.

The Venn diagram peppered with the most traits in the middle came from a 41-year-old friend in academia. He had to think long and hard to come up with a single difference between him and his wife. "Shampoo adverts," he finally hit upon. "The cod science you get in shampoo adverts has an effect on her, but leaves me cold." Laboratoire Garnier aside, the rest of the household is entirely aligned around equal chores, values and ambitions. "Society expects men to be different. If you go by the impression from men's magazines, we're all feckless, cock-driven, football-loving and emotionally infantile," he sighed.

A fiftysomething female media executive agreed that the depiction of men tends to be boorish. "Men are ridiculed more and dismissed – that's because there are much stronger female voices in the media." She, too, put most of the traits in the overlap. "There's very little difference between me and my male friends. We worry about parenting, ageing, maintaining our health, looking good and taking our responsibilities seriously. My husband cares for his mother: 15 years ago the expectation would have been on me to look after my mother-in-law."

When it came to sexual attitudes and behaviour, there was an alignment to some extent. "I'm not yearning for lifelong commitment and monogamy – it makes me feel strangled" and "I used to watch a lot of porn, maybe a couple of times a week": both are comments from women. But the overall sense was that men are still more likely to pursue casual encounters and be able to detach emotion from sex.

"I think it's more to do with the physical goings-on," said a female PR exec in her thirties. "Women almost feel like they've let the man in literally; they've opened themselves up. There are women who can have emotionless sex but there are very few."

And it is a slight shock to the male system to encounter this on occasion. I recall once rolling over for a post-coital hug with someone new I quite fancied only to find she was having none of it. Orgasm (allegedly) achieved, she was up and off, leaving me to feel like the clingy one/get a taste of my own male medicine. "Women are just as up for casual sex, no question," a 35-year-old businessman noted, remembering the time when he'd just emerged from a long relationship into new dating terrain. "Another massive sexual revolution has happened, driven by the net and prevalence of porn."

For all the talk of revolution and closer values, a stark reality kicks in when children come on the scene. "The thing I struggle with the most is the age-old dilemma of career and children," said a corporate lawyer in her early thirties. "It's a misconception that women can have it all if you work hard enough and are organised. In the corporate world, you're fucking deluded." She said that to succeed, women not only have to delegate all their childcare but also publicly avow their commitment to putting work first. "The women who have succeeded in my office basically are men." Interestingly, she "doesn't think it's sexism. I don't blame male employees for wanting to hire an early thirties male over a female. It's disruptive and incredibly difficult to juggle everything."

Among the men I touted the Venn diagram around, only one (shampoo) would consider giving up work to look after the kids, if the wife could become the main bread-winner. A male lawyer in his late thirties physically blanched at the prospect of becoming a house-husband. "I'd feel emasculated, I'd feel upset. I'm not ashamed to say my sense of identity is strongly bound up with my material and vocational success. Whether it be through cultural conditioning or something innate, women in general are more likely to see a happy complete life as involving children, being a mother and maximising their nurturing instinct. I know it's taboo to say this, though." The female PR guru concurred. Although deeply driven, she acknowledges that "women are maternal and more likely to want to nurture or care – maybe it's biological".

If we hail from similar educational and parental backgrounds, and spend so much time working and being around each other, it's not surprising that some of the traditional gender traits have mutually rubbed off. And this goes beyond the moisturised skin associated with metrosexual man a decade or so ago. If metrosexuality was about raiding your girlfriend's toiletry bag, the man of the 2010s is raiding her emotional toolkit. The most prized tool is the capacity to talk. Men seem increasingly able to open up with real candour. Nowadays, male friends can talk with an emotional rawness which not so many years ago would have seen a punitive dead-arm given out for your troubles. And we're more willing to talk to professionals – more men than ever before are going to therapists.

"Women are getting stronger and men are showing more emotions," says women's empowerment guru Lynne Franks, when I call her for a friendly feminist perspective on this alleged gender alignment. Her perspective is that I need some perspective. "There is a small section of young men who have similar values to women. In the big picture, women are still second-class citizens. It'd be lovely if everyone had your liberal attitude – oh, were it more true generally."

I called up the excellent columnist Suzanne Moore, too. "Oh God. Do you want me to be really boring and political about this?" I'm afraid I do. "Well, without addressing class or income you can have this kind of fantasy. Are middle-class women aligning more with middle-class guys? Possibly, to the point they have kids and then income drops. Why ask this question now when all the stats are showing women going backwards? Hit most by cuts, abortion rights under attack, big unemployment, etc."

But I'd say that modern man is equally uneasy when someone is being denied an opportunity because of gender. Just as women will be alarmed to note that men are more likely to educationally underachieve, be incarcerated, a victim of violence or end up homeless (as evidenced in David Benatar's new book The Second Sexism).

Does this make us feminists? Well, I guess that depends on how you define feminism. If it's about championing equal opportunities for everyone while not slapping pointless PC handcuffs on banter and laddism, then count me in. If you're saying sexual penetration by its nature dooms women to inferiority and hope those Newcastle scientists come up trumps on the sperm front, I'm out, sister.

I suspect many women of my mid-thirties cohort might struggle to define where they are on the feminist spectrum, let alone muster that much interest in doing so. After they finished their Venn diagrams, I asked two professional female friends what their views were on feminism. "It's not a topic I've given any thought to," the lawyer said. "If you're talking about Germaine Greer banging on about women being equal, that's dead and buried. People know women are just as capable as men at doing their jobs." The PR guru had thought about the topic. "I hate feminists. It's bollocks. It's feminists who manufacture the issue. Through their obsessive beliefs and claiming so many things to be anti-women, they create the problem."

To tread any further feels like a rather exposed bloke walking into a minefield. But I would hazard that men and women sharing values and experiences does stretch beyond the narrow section of media middle-class types I might mingle with. Tellingly, for BBC 5 Live's Men's Hour, we commissioned a major survey to gauge the psychological impact of the recession on men and women across the country of all classes. A thousand people were interviewed and a whole show set aside. In the end, it barely made a few minutes of air time, as the differences between the genders were negligible: 16 per cent of men were feeling increasingly powerful and hopeless, as were 17 per cent of women. Seven per cent of men and 6 per cent of women were drinking more alcohol. Sex drive was down 8 per cent among men and 6 per cent for women.

What I take from these figures is that modern life is tough, whether you're a man or woman. The gap between our expectations and realities is dangerously wide, work-life balance is being blown apart by technological intrusion, anti-depressant rates are rising, the economy is teetering. Against this, gender wars feel a little obsolete. Maybe it's because (moderate) feminism has actually quietly triumphed – most men would instinctively accept a woman's right for equal opportunities. Perhaps the fuzziness between 'male' and 'female' traits means there's a greater empathy than ever before about what it's like to live life as a man or woman. But it just feels that we've got bigger fish to fry. We can even turn a blind eye to the gender contradictions of Nemo's father, who technically should have turned into a female once the Mrs got eaten by a barracuda.

Men's Hour is on BBC 5 Live on Sundays at 9pm

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments