The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

7 black women who broke barriers in US politics and paved the way for Kamala Harris

Kamala Harris is the first black and South Asian American woman to run as vice president on a major political party’s ticket, writes Sabrina Barr

On Tuesday 11 August, Democratic presidential nominee Joe Biden announced that he had chosen Californian senator Kamala Harris as his running mate, describing the former state attorney as “a fearless fighter for the little guy, and one of the country’s finest public servants”.

The former vice-President said that he felt “proud to have her as my partner in this campaign”, which will see the 77-year-old go up against US president Donald Trump in the 2020 presidential election in November. Harris praised the presidential candidate for his “audacity to choose a black woman to be his running mate”.

“How incredible is that? And what a statement that is about Joe Biden,” Harris said during an interview for the virtual The 19th Represents Summit. “That he decided he was going to do that thing that was about breaking one of the most substantial barriers that has existed in our country – and he made that decision with whatever risk that brings.”

Harris, who was born in California in 1964 to Shyamala Gopalan, a biologist from India and Donald J Harris, a Stanford University professor from Jamaica, was elected senator of California in 2016, becoming the second black woman and the first South Asian American senator in US history.

As Biden’s running mate, the former attorney general of California has become the first black woman and person of South Asian descent to run as vice president on a major political party’s ticket.

If Biden wins the election, she will become the most senior black woman in US political history.

Before Harris, several black women rose the ranks in the US political sphere, bidding to become president, speaking at the Democratic National Convention and serving in the presidential cabinet among their achievements.

Shirley Chisholm

“I am the candidate of the people, and my presence before you now symbolises a new era in American political history.”

Shirley Chisholm’s signature campaign slogan, “unbought and unbossed”, were words she not only spoke to, but also lived by. Born in Brooklyn, New York in 1924, Chisholm was a second-generation immigrant, her father coming from Guyana and her mother from Barbados.

After graduating cum laude from Brooklyn College in 1946, Chisholm became a nursery school teacher before earning a master’s degree from Columbia University in early childhood education in 1952. After becoming director of several daycare centres and an educational consultant for the Division of Day Care, she became a member of the National Association for the Advancement of Coloured People and the League of Women Voters, using her voice to campaign against racial and gender discrimination.

In 1964, Chisholm became the second African American to be elected to the New York State Legislature, before making history four years later as the first black woman to be elected to Congress. Known for her powerful speeches and quick-witted debating comebacks, she went on to serve seven terms in the House of Representatives, introducing over 50 pieces of legislation.

In 1971, Chisholm became a founding member of the National Women’s Political Caucus alongside Betty Friedan and Gloria Steinem. The following year, Chisholm set her sights on the US presidency, running for the Democratic nomination. Announcing her presidential bid, she said, “I am not the candidate of black America, although I am black and proud; I am not the candidate of the women’s movement of the country; although I am a woman, and I am equally proud of that. I am the candidate of the people, and my presence before you now symbolises a new era in American political history.”

Chisholm survived several assassination attempts during her presidential campaign, in addition to being barred from participating in the majority of the televised primary debates, which resulted in her having to take legal action to ensure she could join. Chisholm, who authored Unbought and Unbossed in 1970 and The Good Fight in 1973, died at the age of 80 in 2005. 10 years later, she was posthumously awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by then-president Barack Obama.

Charlotta Bass

“I am strengthened by thousands on thousands of pioneers who stand by my side and look over my shoulder.”

Before Harris, the first black woman to run for vice president was Charlotta Bass, who bid for the position in 1952 on the ticket of the left-wing Progressive Party, alongside presidential candidate and lawyer Vincent Hallinan.

Born in Sumter, South Carolina in 1874, Bass’s career in politics came about following a long bout in journalism, which began in her twenties when she started working at local Rhode Island newspaper the Providence Watchman. After moving to the Golden Coast, Bass took her penmanship to another paper called the Eagle, proving herself to such an extent that when the founder of the company died, the paper was put in her hands.

Working alongside editor Joseph Bass (whom she later married), Bass published the paper – which she renamed the California Eagle – from 1912 to 1951, utilising her platform to raise awareness of racial discrimination and civil rights issues. Together, the couple spoke out against police brutality, segregation and the Ku Klux Klan, which resulted in them facing several menacing threats from the white supremacist group.

Bass’s decision to use her voice to speak out against injustices in society put her on the radar of the FBI, who placed her under surveillance amid claims that she was a Communist, though Bass denied any such connection to the Communist Party.

Prior to her vice presidential nomination, Bass was already making headway in the world of politics, becoming co-president of the Universal Negro Improvement Association in the 1920s and creating the Home Protective Association, which fought against restrictive covenants that hindered people of colour from being able to purchase homes. In 1952, upon her nomination as vice president for the Progressive Party, Bass said:

“I stand before you with great pride. This is a historic moment in American political life. Historic for myself, for my people, for all women. For the first time in the history of this nation a political party has chosen a Negro woman for the second highest office in the land. It is a great honour to be chosen as a pioneer. And a great responsibility. But I am strengthened by thousands on thousands of pioneers who stand by my side and look over my shoulder – those who have led the fight for freedom – those who led the fight for women’s rights – those who have been in the front line fighting for peace and justice and equality everywhere. How they must rejoice in this great understanding which here joins the cause of peace and freedom.”

Barbara Jordan

“I am not going to sit here and be an idle spectator to the diminution, the subversion, the destruction, of the Constitution”

Barbara Jordan’s opening remarks at a hearing during the impeachment process of Richard Nixon – a 15-minute, televised speech – became one of the defining moments of her political career. The member of the House Judiciary Committee stunned those watching in 1974 when she emphasised the “faith” she felt in the US Constitution, and the adamance she felt in protecting said Constitution from “diminution, subversion and destruction”. In her obituary published in The New York Times in 1996, the paper described her oratory skills as “Churchillian”, drawing parallels between Jordan’s mannerisms with the British wartime prime minister.

Before becoming the first African American woman from the deep South to become a congresswoman in the US, Jordan embarked on a career in law, launching a private law firm in 1960. However, politics was clearly on her mind at the time, as she bid twice for a seat on the Texas House of Representatives in the early 1960s, both times being unsuccessfully. Nonetheless, in 1966 Jordan prevailed, becoming the first black woman to be elected to the Texas Senate and the first African American to become a state senator since 1883.

Following her landmark speech during the Nixon impeachment process, which occurred amid the Watergate Scandal, in 1976 Jordan became the first African American and the first woman to deliver a keynote speech at the Democratic National Convention. Jordan stressed the ethos of the Democratic Party, saying the party believes “in equality for all and privileges for none”. “This is a belief that each American, regardless of background, has equal standing in the public forum – all of us,” she said.

Jordan was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by President Bill Clinton in 1994, in addition to receiving the Spingarn Medal from the NAACP, an award given every year to people of African descent and American citizenship “who shall have made the highest achievement during the preceding year or years in any honourable field of human endeavour”.

Condoleezza Rice

“We must use American diplomacy to help create a balance of power in the world that favours freedom.”

As the first black woman to become appointed national security adviser and the first black female secretary of state for the US, Condoleezza Rice held a great deal of power within the US government. As secretary of state, she made it her mission to enact “transformational diplomacy”, a term she coined that she hoped would help create democratic, well-governed states around the world.

Rice brought a great deal of political expertise to the White House, having earned a degree, a master’s degree and a PhD in political science. This expertise is what brought her into the presidential fold, as she was recruited onto the United States National Security Council during the presidency of George H W Bush after being scouted while working as a professor at Stanford University.

In 2001, the year that George W Bush assumed the presidency, Rice was named United States national security advisor, the first black woman to assume the role. Two years after assuming the position, the invasion of Iraq took place, an event that Rice supported. During Bush’s second presidential term, which began in 2005, Rice became the first black woman to become secretary of state. Following her confirmation hearing, she said that “we must use American diplomacy to help create a balance of power in the world that favours freedom. And the time for diplomacy is now”.

In 2006, a release was published by the US Department of State regarding Rice’s plans to collaborate with the US’s “many partners around the world to build and sustain democratic, well-governed states that will respond to the needs of their people – and conduct themselves responsibly in the international system”, an objective she called “transformational diplomacy”. “Transformational diplomacy is rooted in partnership, not paternalism – in doing things with other people, not for them,” she stated. “We seek to use America’s diplomatic power to help foreign citizens to better their own lives, and to build their own nations, and to transform their own futures.”

Carol Moseley Braun

“My presence in and of itself will change the US Senate.”

Carol Moseley Braun was destined for a career in politics from a young age, organising a sit-in at a segregated restaurant and marching alongside Martin Luther King Jr during a demonstration against Chicago housing conditions as a teenager. After earning political science and law degrees, Moseley Braun demonstrated her prowess as an impressive prosecutor in the office of the US attorney in Chicago, covering areas including the environment, health and housing from 1973 to 1977, her work even being recognised with the attorney general’s special achievement award.

In the late 1970s, Moseley Braun entered the political domain, elected as a member of the Illinois House of Representatives. She rose the ranks to become assistant Democratic majority leader, the first black woman to hold the position, and upon her retirement from the role in 1987, she was dubbed the “Conscience of the House” by her peers, evidently demonstrating the high regard with which she was perceived.

The pioneer continued to make history, becoming the first African-American woman to be elected to the US Senate in 1992 as a representative of Illinois. Shortly after assuming her position, Moseley Braun stated: “I cannot escape the fact that I come to the Senate as a symbol of hope and change. Nor would I want to, because my presence in and of itself will change the US Senate.”

Moseley Braun served one term on the US Senate, during which time she voted against the death penalty, advocated for gun control measures and was pro-choice. Moseley Braun also staged a demonstration on the US Senate floor in the early 1990s against the rule that women were not allowed to wear trousers, a regulation that was overturned later that year under the condition that they also had to wear jackets.

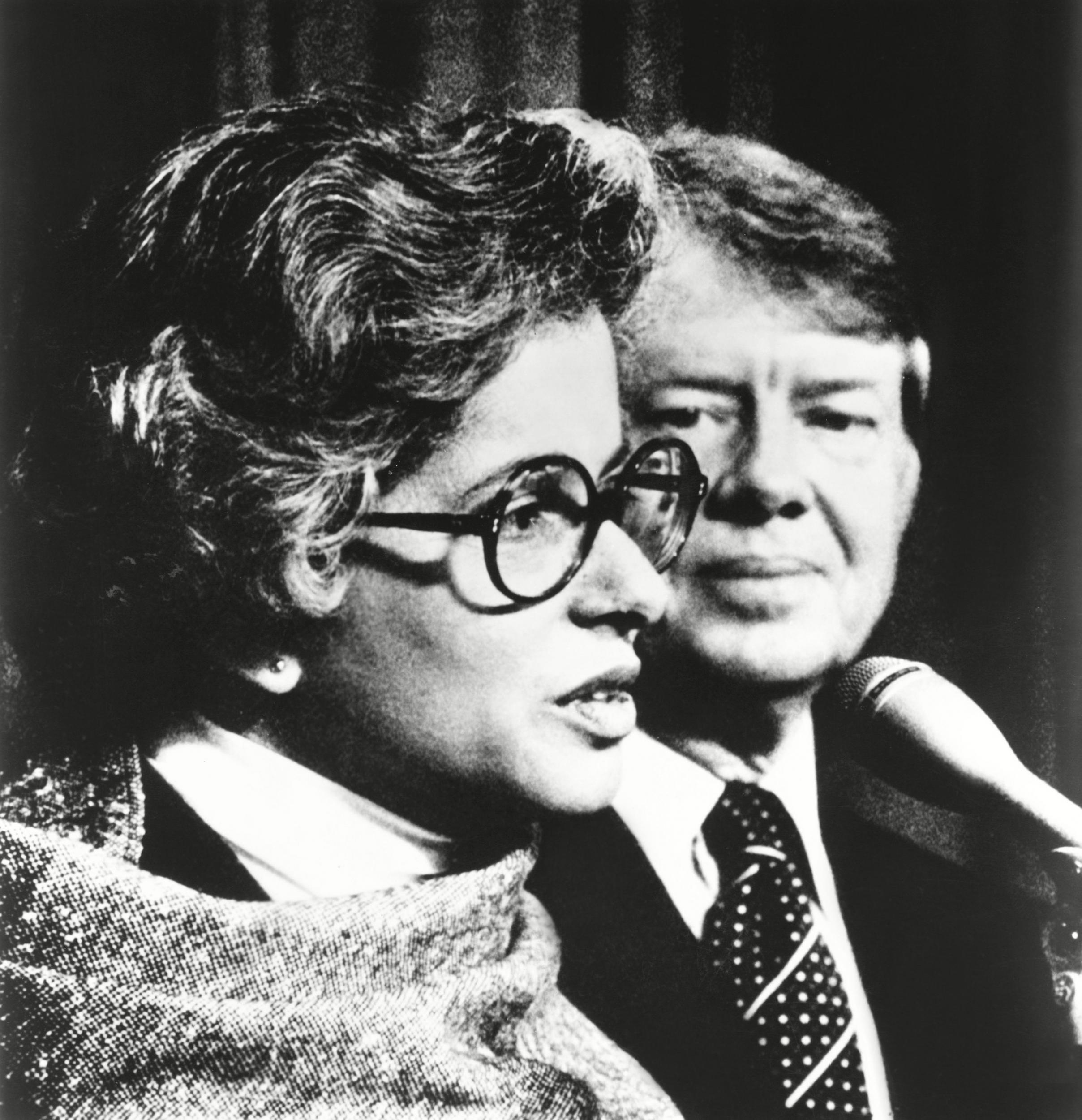

Patricia Harris

“I didn’t start out as a member of a prestigious law firm, but as a woman who needed a scholarship to go to school. If you think that I have forgotten that, you are wrong.”

Patricia Harris worked alongside several presidents throughout her political career, becoming the first African American woman to serve in the presidential cabinet during the presidency of Jimmy Carter in 1977, named co-chair of the National Women’s Committee for Civil Rights by President John F Kennedy in 1963 and was made an American envoy by President Lyndon Johnson in 1995.

Born in Mattoon, Illinois in 1924, Harris’s involvement in politics started during her university years, which saw her become vice chair of the student chapter of the NAACP at Howard University and take part in one of the first lunch counter sit-ins in America. 15 years after graduating from university, Harris earned a law degree from George Washington University, resulting in her working for a short stint as an attorney for the US Department of Justice.

Upon her appointment as an American envoy by President Johnson, Harris expressed her pride over the position, in addition to her frustration that no black women had taken on the role before her. “I feel deeply proud and grateful this President chose me to knock down this barrier, but also a little sad about being the ‘first Negro woman’ because it implies we were not considered before,” she stated.

It was in the 1970s that Harris became a member of Carter’s presidential candidate, becoming the first black woman to serve as cabinet secretary as secretary of housing and urban development. Following her nomination, Harris was questioned by a senator during her cabinet hearing regarding her ability to defend the interests of poor members of the public.

Harris replied: “I am one of them. You do not seem to understand who I am. I am a black woman, daughter of a dining-car worker. I am a black woman who could not buy a house eight years ago in parts of the District of Columbia. I didn’t start out as a member of a prestigious law firm, but as a woman who needed a scholarship to go to school. If you think that I have forgotten that, you are wrong.”

Loretta Lynch

“I stand before you so thrilled, and, frankly, so humbled to have the opportunity to lead this group of wonderful people who work all day and well into the night to make that ideal a manifest reality, all as part of their steadfast protection of the citizens of this country.”

In 2015, Loretta Lynch became the first black woman to become appointed US attorney general, a position she was granted by President Barack Obama. Her path towards becoming attorney general began in the 1980s, when she graduated from Harvard Law School and embarked upon a career in law.

After making a name for herself as a prosecutor in the office of the US attorney for the Eastern District of New York working on drug and violent-crime cases, in 1999 President Bill Clinton made her attorney of the office, a position she held for two years and then again for another five from 2010 to 2015. Following her second tenure as US attorney for the Eastern District of New York, President Obama deemed Lynch worthy to replace Eric Holder as attorney general of the US.

Upon his nomination of Lynch, Obama praised the attorney’s “principles of fairness, equality, and justice”, saying that she has “striven to make a difference for the people she serves.”

“It’s in her blood,” he said. “Her grandfather, a sharecropper in the 1930s, helped folks in his community who got into trouble with the law and had no recourse under the Jim Crow system. She rode her father’s shoulders to his church, where students would meet to organise anti-segregation boycotts. The sense of justice she absorbed as a young girl is what she will bring to bear at the Department of Justice.” In response, Lynch said she felt “thrilled” and “humbled” by the nomination.

In 2016 during her tenure as attorney general, Lunch wrote an op-ed about the hardships former criminals face when they re-enter society from prison, emphasising that “for far too many Americans, re-entry has become an all-but-impossible task”. “As we continue striving to make our criminal justice system smarter and fairer, we must ensure that those returning from prison come home to a meaningful second chance,” she said.

That same year, Lynch intervened in the case of the death of Eric Garner, replacing the Brooklyn agents and lawyers investigating the case with agents from outside New York, in a move that was described as “highly unusual”. Garner died on Staten Island in 2014 after a New York police officer put him in a chokehold during his arrest. The police officer was fired in 2019, with no charges being brought against him.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks