The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

UK economy: Are retail sales really falling at their fastest rate since the recession? And does this mean we should be alarmed?

Is the economy really in trouble as we rush towards Brexit in 2019? Are households cutting back on spending? Just how worried should we be?

Headlines on Friday spoke of plunging retail sales and harked back to the last recession.

So is the economy really in trouble as we rush towards Brexit in 2019? Are households cutting back on spending? Just how worried should we be?

Are retail sales really falling at their fastest rate since the recession?

That’s certainly what one survey suggests.

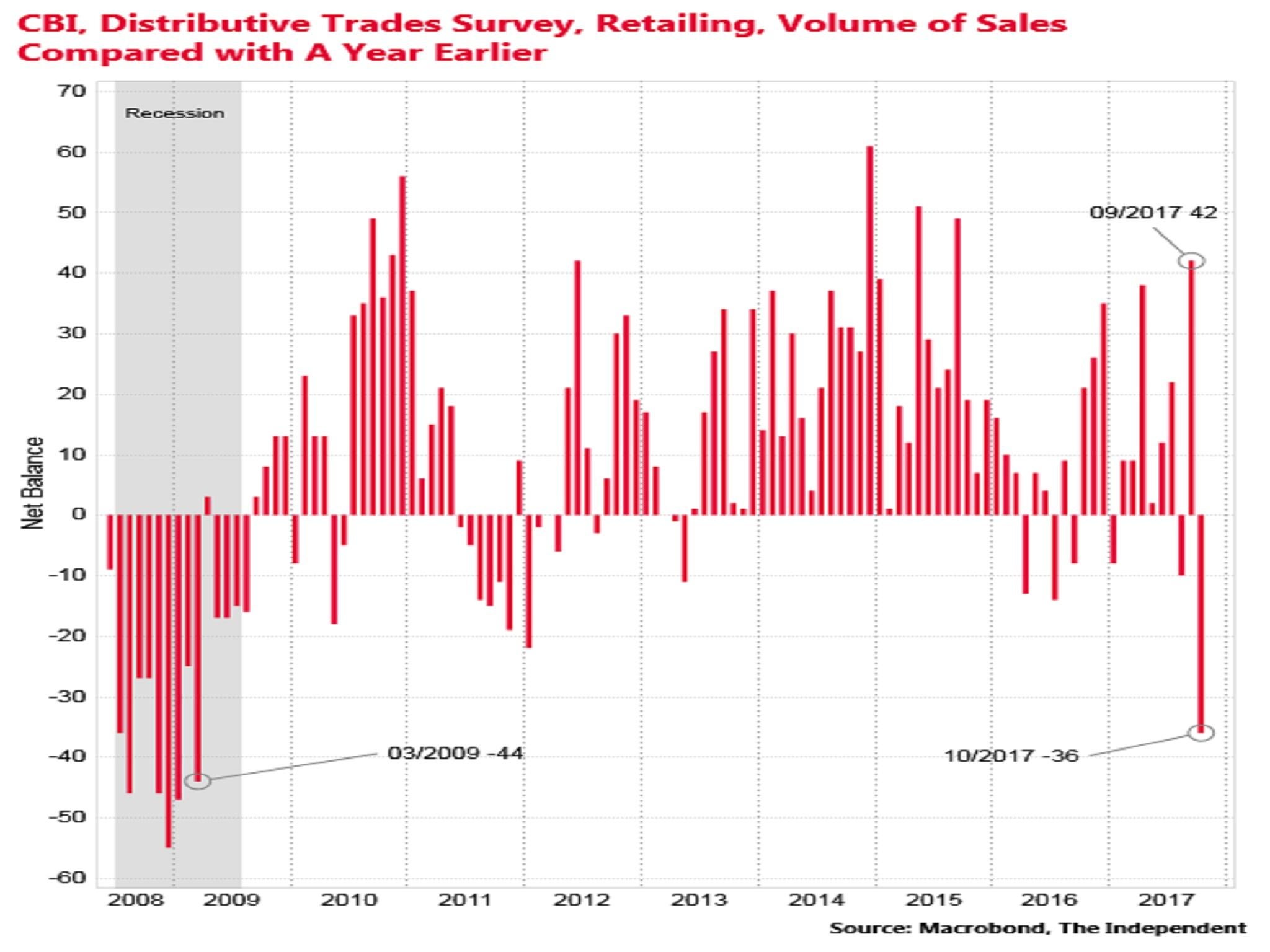

The CBI’s latest monthly Distributive Trades Survey, released on Thursday, showed 15 per cent of retailers reported sales volumes were up in October on the same month a year earlier versus 50 per cent who reported they were down.

That gave a rounded net reading of minus 36 per cent. This was the worst reading for this survey since March 2009, when the UK was in recession.

Does that mean we are heading for another recession?

The CBI figures are certainly weak, but the survey results are volatile.

The net balance for reported sales volumes from retailers was plus 42 per cent last month, the highest since 2015.

Based on this historic pattern it’s possible the next reading in November could show a significant bounceback.

The CBI survey has also not been a particularly reliable leading indicator for official sales figures.

The most recent Office for National Statistics figures, incidentally, showed retail sales volumes fell 0.8 per cent in September, which was somewhat disappointing but not calamitous.

Going into the 2008-09 recession volumes were falling at a quarterly rate of 3.5 per cent.

It’s also unwise to place much emphasis on a single survey.

So what other leading indicators are there?

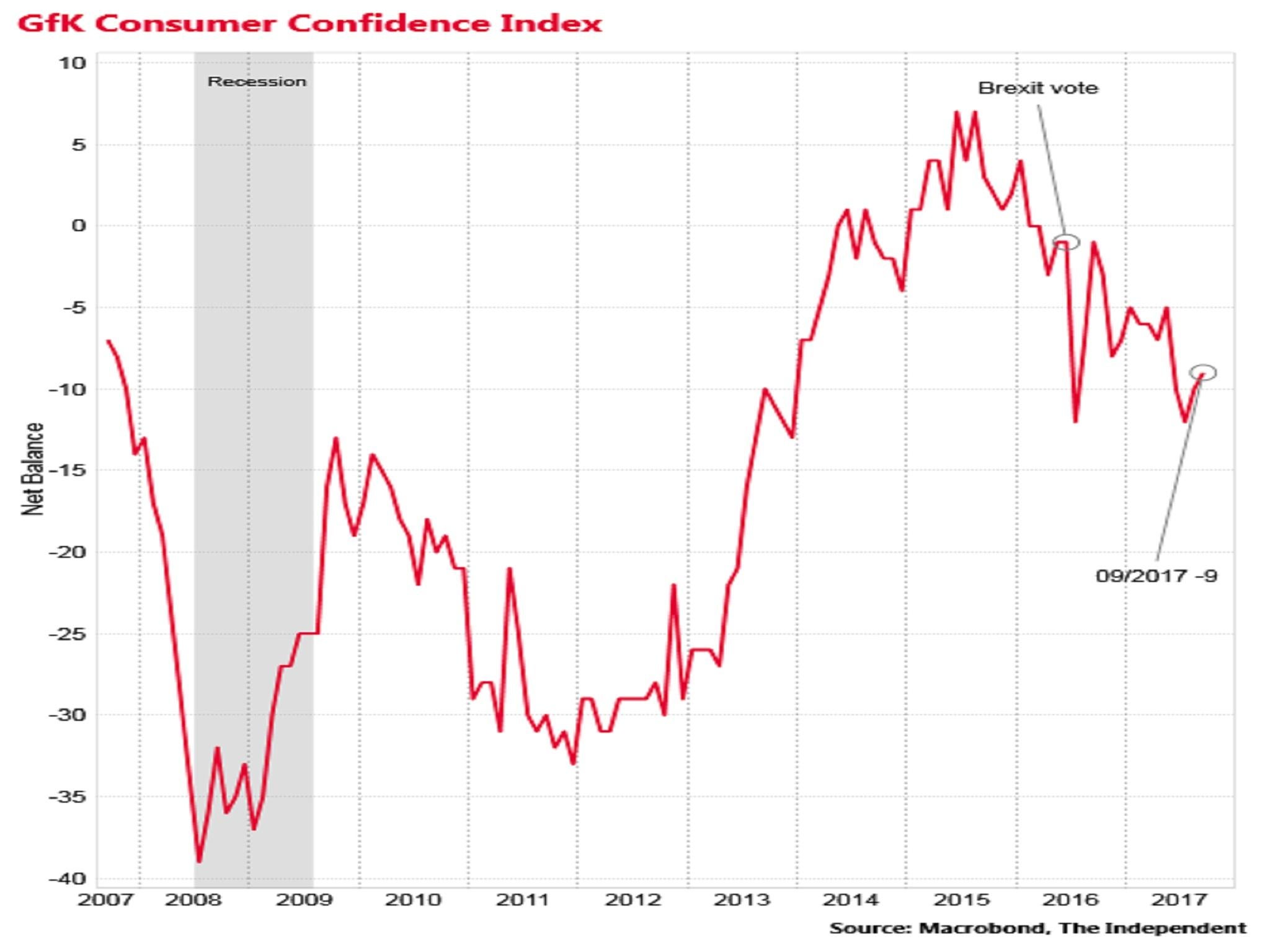

Consumer confidence indicators are often used.

One series from GfK shows that there has been a slip since the start of the year and it fell to its lowest level since the 2016 Brexit referendum in July (minus 12).

However, it has come back a bit since then with the latest reading at minus 9.

Moreover, at the time of the 2008-09 recession this indicator was down at minus 35.

But the picture is mixed.

Business surveys have shown the opposite trend, with a weakening in optimism from firms' managers in recent months.

But don't we already know that the economy is slowing down?

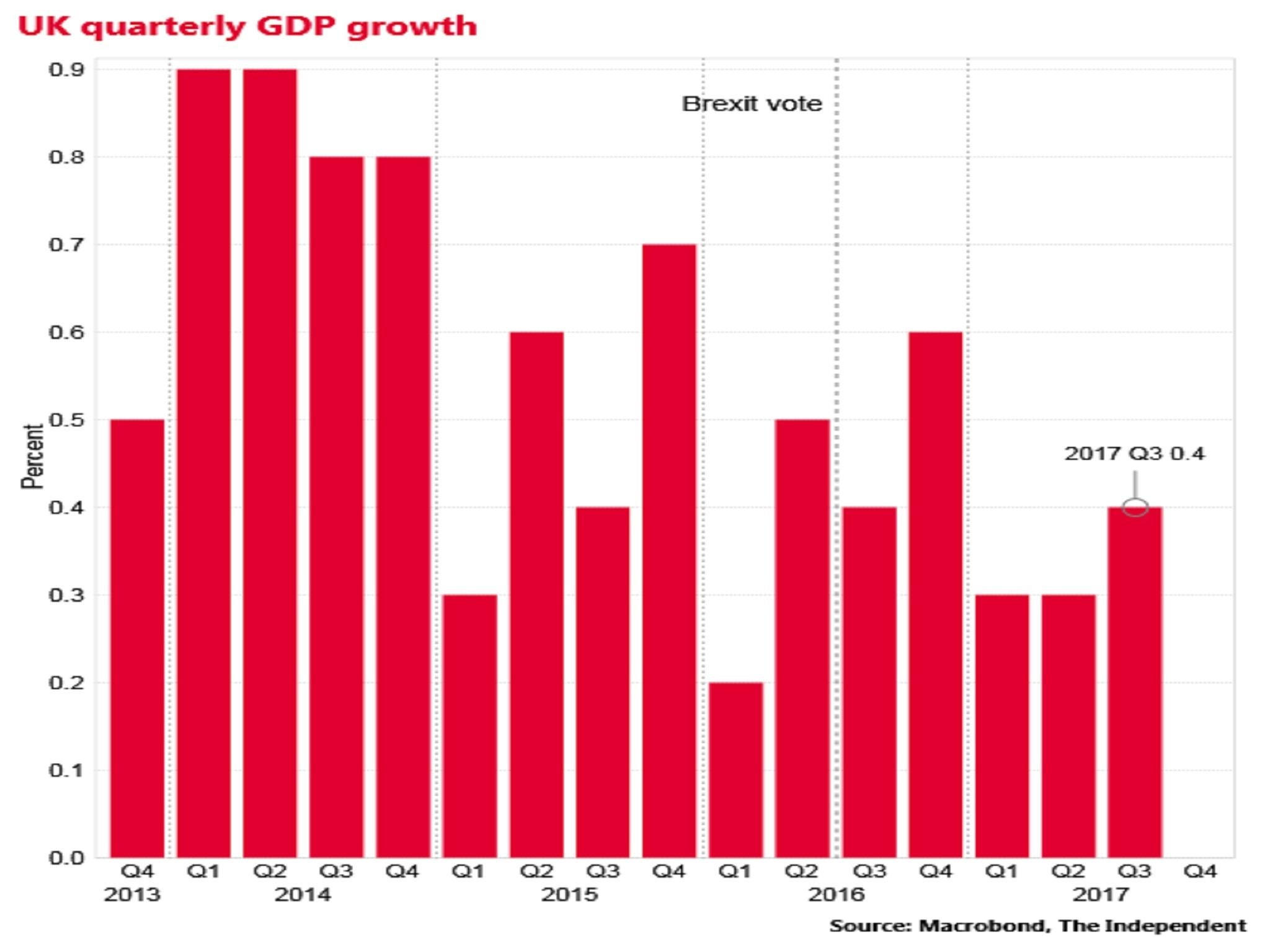

Though the pace of GDP growth picked up slightly to 0.4 per cent in the third quarter of 2017, according to the ONS’s early estimate, this is below the 0.6 per cent rate seen at the end of 2016.

Most economists have been revising down their growth forecasts this year.

Yet a recession is defined as negative GDP growth for at least two quarters.

There are virtually no forecasters predicting this, even after the latest CBI survey.

But aren’t interest rates going to rise soon?

The Bank of England is widely expected by financial markets to raise its official interest rate next month from 0.25 per cent to 0.5 per cent in order to rein in inflation, which hit 3 per cent in September.

An increase in Bank rate would automatically put up the cost of borrowing for people with tracker mortgages.

As an illustration, someone with a 25-year £250,000 repayment tracker mortgage paying 2 per cent interest could see their monthly £1,100 repayment rise by around £30.

Yet most households do not have a mortgage and, of those that do, a majority are on fixed-rate borrowing deals, meaning the direct economic consequences of an increase in rates should not be overstated.

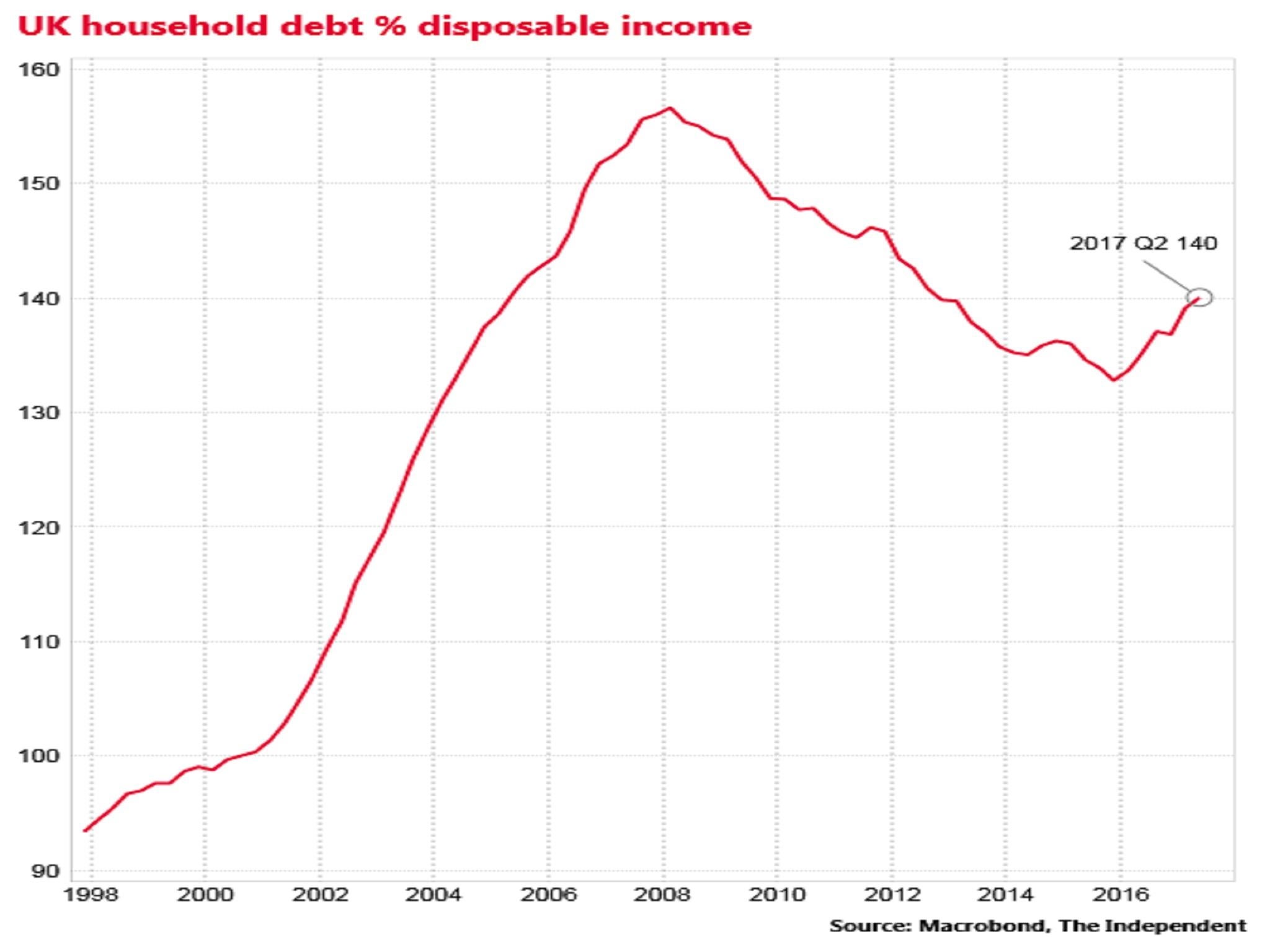

But aren't UK households vulnerable because of their massive debts?

Unsecured consumer borrowing – covering areas such as new car loans and credit cards - is still growing at a double digit pace.

And the aggregate level of household debt relative to household incomes (at 140 per cent at the end of the second quarter) is rising again.

There’s no doubt that this is helping support economic growth.

Virtually all of the UK’s GDP growth in the first half of the year came from household consumption, rather than net exports and business investment.

If households were to suddenly stop spending and borrowing it would undoubtedly inflict a severe shock on the economy.

It’s not inconceivable that this could happen, especially if people started to believe a disastrous "no deal" Brexit in March 2019 is more likely than not.

Yet most forecasters expect a slowdown rather than a sudden stop in spending, as households moderate their consumption in the face of higher inflation, weak income growth and an increase in interest rates.

This would slow the economy and help deliver disappointing rates of growth, certainly relative to Europe, which is experiencing a cyclical recovery.

They may turn out to be wrong (and if the awful CBI survey data is matched by official releases over the coming month there will be a rethink) but a return to recession for the UK is not the current expectation of the vast majority of professional forecasters.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks