UK interest rates: What could an increase mean for British families and companies?

The implications for mortgage borrowers, savers, companies and holidaymakers

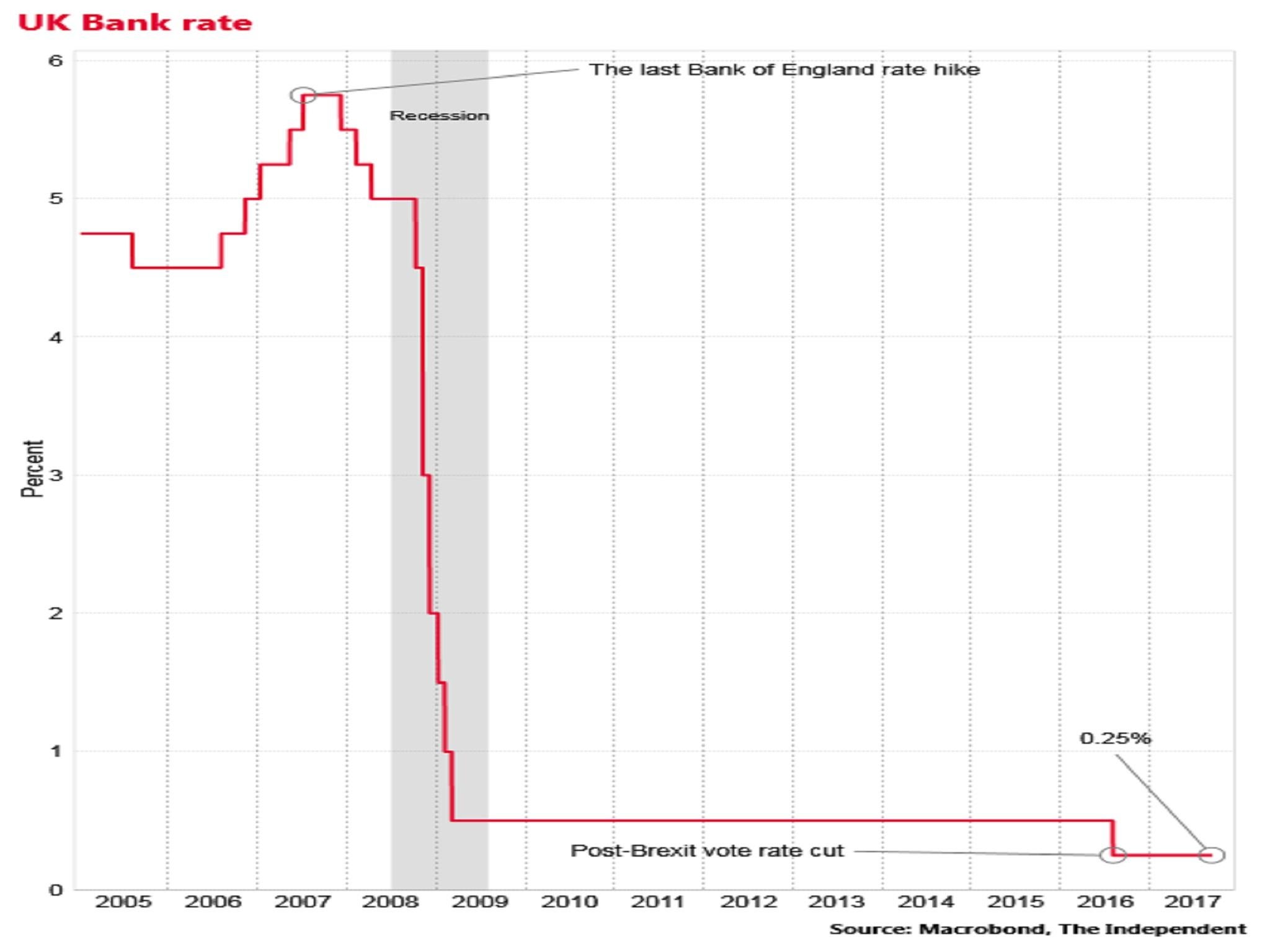

The Bank of England signalled strongly in the minutes of its latest meeting on Thursday that interest rates will soon rise – possibly as early as November.

But what does this mean, in practical terms, for British families and firms?

Higher mortgage repayments...

A hike in rates by the central bank traditionally means an increase in people’s monthly mortgage repayments.

And people on tracker mortgages – where repayments vary with the Bank of England’s base rate – will rapidly be made worse off from a Bank of England rate rise.

As an illustration, someone with a 25-year £250,000 repayment tracker mortgage paying 2 per cent interest could see their monthly £1,100 repayment rise by around £30, if rates rise go back to 0.5 per cent.

However, the number of people on tracker mortgages has fallen in recent years, as people have been moving on to fixed-rate deals.

Almost 90 per cent of new loans are fixed rate, with around 57 per cent of the total stock of mortgage loans on a fixed rate basis.

That means many people will only feel the impact of the rate rise when the come to remortgage.

It’s possible that some over-extended mortgage borrowers could find themselves unable to shoulder an increase in repayment costs, stemming from a Bank rate rise to 0.5 per cent.

But commercial banks have been under intense regulatory pressure in recent years not to lend to people who would be unable to cope with modest rate rises, and surveys for the Bank have suggested the vast majority of families would not fall into difficulties.

However, it might make families less inclined to spend in the shops, which could further slow the wider economy.

Pricier unsecured loans

The average interest rate on a £5,000 personal loan has come down from 9.3 per cent at the time of the Brexit vote in 2016, to just 8 per cent today.

The rate on a £10,000 loan is down from 4.3 per cent to 3.8 per cent over that same period.

This reduction has likely been driven by the Bank’s August 2016 cut in interest rates – and this would probably be reversed if rates returned to 0.5 per cent.

However, the Bank is concerned about the sustainability of fast-rising unsecured borrowing, so it would regard this type of credit re-pricing as welcome.

Tighter credit for firms...

Traditionally, movements in the Bank of England base rate also change the price of credit available to businesses.

Yet this normal transmission mechanism has been somewhat unreliable since the 2008 financial crisis.

Banks have been slow to pass on the many reductions in the general cost of borrowing to firms. There has also been very muted demand from companies to borrow.

The increase in the Bank rate may actually make little difference to the price of credit offered to firms – or their willingness to take it up, especially as Brexit-related uncertainty and weakening consumer demand is already deterring investment and expansion.

More interest for savers...

Ordinary depositors should see higher rates of interest on their current account deposits.

The average interest on instant access savings accounts has shrivelled to a measly 0.14 per cent a year on balances, down from 0.4 per cent in June 2016.

It’s possible that banks may try to avoid passing on the full impact of the rate hike to savers in order to boost their profits – although that would probably result in a tremendous public backlash.

Less expensive holidays...

Interest rate hikes are associated with increases in the exchange rate, meaning a stronger pound and therefore cheaper holidays for Britons travelling abroad.

We’ve already seen some of that effect, with sterling bouncing around 1 per cent to $1.3347 and €1.1214 in the wake of the Bank’s meeting on Thursday.

It could rise further still in the coming months, if the Bank sends out more signals on the timing and pace of rate rises.

However, the UK currency still remains well below the $1.48 and €1.30 figures from before the Brexit referendum of June 2016.

Many families who went abroad this summer will have experienced a nasty shock over how little the pound now buys.

And even if rates do rise, it’s most unlikely that the sterling exchange rate will be returning to where it was in the summer of 2016 any time soon.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments