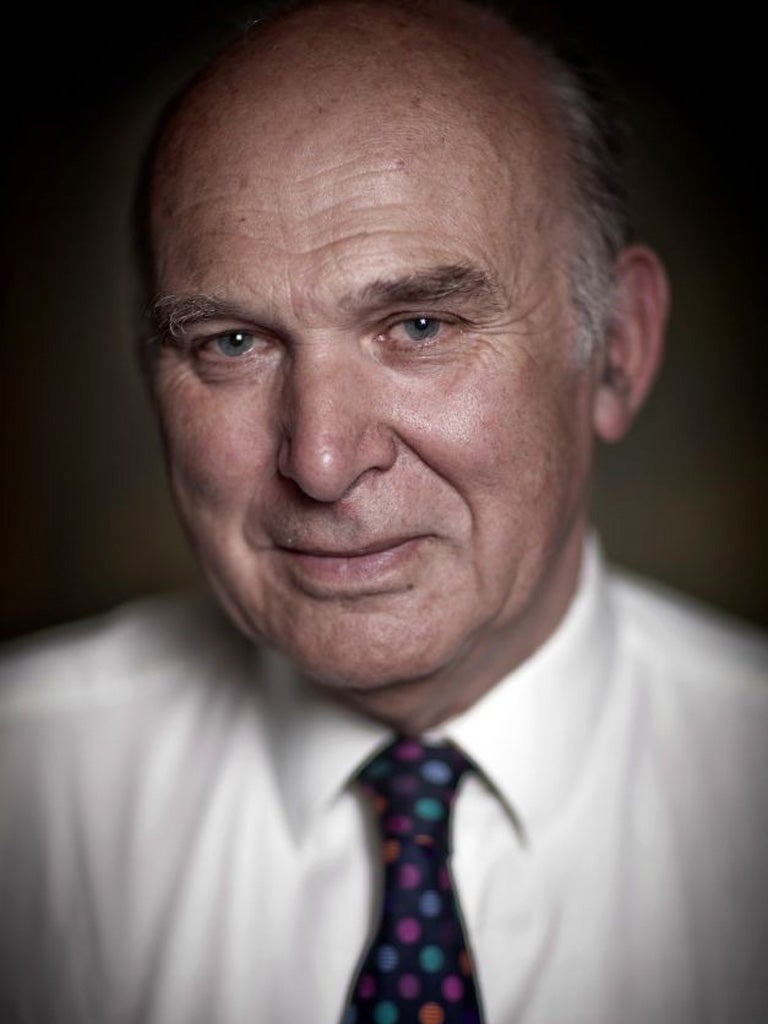

Vince Cable: 'It's ultimately where our increasing living standards come from'

The Business Secretary tells James Ashton that his vision for Britain's manufacturing industry is gradually coming into focus

Vince Cable nods through the glass to the atrium outside his office. He sat there 30-plus years ago when John Smith, the late Labour leader, was Industry Secretary in James Callaghan's Labour government.

It was the Winter of Discontent, peppered by industrial uprisings. With the economy in turmoil, Cable, today's Business Secretary, was Smith's special adviser when the Japanese were first invited to invest in Britain.

"It was highly controversial at that time because of the war, and it required a certain amount of courage for ministers and trade unions to be able to say we welcome these people here," Cable remembered. "But they completely transformed particularly the car industry with their techniques and electronics. It was a very big step."

If Cable's memory of Smith is the past, he hails his recent visit to Jaguar Land Rover at Gaydon in Warwickshire as the future.

"There was this enormous room, which had about 1,500 people in it – the heart of the British motor industry. They were all at desks with CAD software models on their computer screens. That is where the value added is in the British car industry; they're highly qualified graduates doing very sophisticated things with 3D kits – it isn't production-line employment."

In some quarters they call him the Anti-Business Secretary, but in manufacturing, Cable is right at home – especially if he is out and about kicking the tyres in a car factory.

His warmth for manufacturing has been mirrored by a distinct coolness towards financial services. He's meant to be in favour of all business, but a desire to rebalance the economy means anything Made in Britain finds favour with him.

"It's important to emphasise it – not in an irrational, emotional way – because manufacturing is disproportionately traded and exported, and also for its contribution to productivity, which is ultimately where our increasing living standards come from," he said.

Manufacturers share the same concerns over Britain as a home to do business as any other industry: excessive red tape, poor infrastructure and high taxes.

The difference the "makers" must also contend with is the impression that they are in terminal decline. Behind the rosy glow given off by ministerial tours to hi-tech plants, there are plenty of figures that make uncomfortable reading. Manufacturing's share of the UK economy stood at 23 per cent overall in 1980 – the year after the Callaghan government was swept from office by Margaret Thatcher – to just 10 per cent today.

"It is about the same as France and the United States – not bad when you express it like that," Cable said, "but way below Germany and Japan."

Over the same period, the sector's workforce has shrunk by around two thirds to 2.3 million.

By stepping up exports, especially beyond the crippled eurozone, Cable thinks Britain can add "a few percentage points quite realistically" to manufacturing's share of the economy before the Coalition's term is up in 2015. The idea is that the economy as a whole would be growing by then too.

Part of that growth would come from selling more abroad, but the rest would be contributed by repatriating components here – essentially rebuilding the supply chain which companies claim has been damaged by the hollowing out of Britain's industrial heritage.

The key is pulling together a strategic vision – something Cable has grumbled about before.

"More needs to be done," he said.

His model for success is the car industry, where production jumped 6 per cent to 1.34 million vehicles last year and could pass the 1972 record of 2.33 million cars by 2016 because of new investment pledged by the likes of Toyota, Nissan and Honda.

"I think that the deeper thing is the psychological move… that people are now much more positive."

Recent manufacturing figures from the CBI employers' body contained encouraging signs, but pockets are still struggling like the steel industry because of excess capacity and construction products – bricks, glass and pipework – which make up about one-quarter of the overall sector, because the building sector is still stagnant.

In cars, Cable credits the work of the Automotive Council that brings together the big producers, governments and technical experts around one table to identify issues such as research funding, training and procurement. The aerospace, rail and energy sectors are getting similar treatment. But still companies complain of a blizzard of incremental new initiatives, with too few having a real impact on their working lives.

"I don't think it is dribs and drabs, but there are some sectors that are perfectly happy just getting on and doing their thing," he said.

"The food and drink manufacturers are a very important sector and they do a lot of very sophisticated process innovation but they don't come to government very often. In aerospace, they come all the time because you're dealing with big public-sector contracts.

"The interaction is variable, but that doesn't mean it's not coherent."

Having picked areas such as aerospace and food as winners, does that mean smaller businesses that don't fit a sector will fall by the wayside?

"I can't think of instances where we've had to say: 'OK, we're going to give you a bit of help, but sorry that means you'll have to go away'. That kind of choice hasn't had to be made," Cable replied.

"If you're talking about a finite pot of money that kind of issue will arise, but I can't think of any instances."

Aside from the other issues that have to be addressed, it is skills – or a shortage of them – that worries every chief executive in industry. Some 587,000 new engineers and technicians are needed by 2017 just for our manufacturing base to stand still.

Cable admits it can be depressing to visit a factory in an area of high unemployment where the management moan they just can't get the staff. But he reckons that demand for engineering has held up in this year's crop of university admissions.

Would more role models help – someone for schoolkids to look up to instead of the likes of Cheryl Cole and David Beckham?

"It's not necessarily the role models in the media, but it's the local community," he said. "It's having somebody who has got a steady job and is well paid.

"You've got to have engagement but you've also got to have basic qualifications. It's difficult for people to do an engineering degree unless they've got further maths, so that raises questions about the school system."

Writing this week in The Independent, Dick Olver, the chairman of defence giant BAE Systems, suggested that every government policy should be put to a "growth test" to check whether or not it was beneficial to the economy.

Cable, who has thought nothing of lobbing the odd hand grenade into the Coalition despite being a senior member of it, insists ministers are already on the same page. His growth review took various departments to task.

"I think that without becoming bureaucratic and formal we do recognise that's a legitimate test of policy. I'm pretty confident that my colleagues, most of whom are running economic ministries, are very well aware of what they can contribute."

The example he gives is the Department for Health, under Andrew Lansley, who is looking at how the NHS can be used to promote clinical trials which will support the growth of biosciences.

Where Lord Mandelson dashed around the country writing cheques for regional assistance grants, Cable turns up without money, but bosses on the ground say he listens rather than just talks.

Talking to Steve Girsky, the vice-chairman of General Motors, helped to save the car giant's Ellesmere Port factory on Merseyside as well as 2,100 jobs.

Cable knows his biggest test lies ahead, though. There are encouraging signs, but can the "march of the makers" deliver real jobs and growth in time for the next election in 2015?

All abroad: UK firms in foreign hands

Ministers are keen to demonstrate that Britain is open for business – but those open markets have led to a rash of takeovers of UK companies.

Cement firm Blue Circle, gases group BOC and ports operator P&O have all fallen into foreign hands in the last decade, as well as mobile phone firm O2 and, in the last few weeks, IT services group Logica.

Critics fear that the loss of ownership means loss of high-quality jobs and corporate influence from these shores.

Vince Cable argues it doesn't always mean Britain suffers in the end. When he first arrived as business secretary, Cadbury was in the process of being swallowed whole by US processed cheese maker Kraft.

"I confess I had mixed feelings about it," he said, "but when you look now at what has happened, Kraft has brought sophisticated research and development into Cadbury's Bourneville operation."

Again, he turns to the car industry, where Tata Group acquired Jaguar Land Rover in 2008.

"They're completely committed to the UK," Cable said. "All the others – BMW, Ford and General Motors – they're good British corporate citizens and the fact that they don't have ultimate British ownership is not relevant. I think it puts us at an advantage because we're tapping into the best of multinational companies."

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks