‘We are second-class citizens’: Brexit delays push lorry drivers to quit

‘We drive 44-tonne killing machines. We are professionals, and in Europe we are treated like professionals, but in the UK we aren’t’

Huge queues, long delays and a deluge of paperwork due to Brexit are contributing to unsustainable mental health pressures on lorry drivers, causing some to drink excessively and others to quit their jobs, industry insiders have said.

Drivers report that chaos at UK ports from 1 January, including 20-mile tailbacks at Dover, is frequently adding four or five hours of waiting time on top of gruelling 10-hour driving shifts, potentially putting road safety at risk.

“The pressures facing drivers now mean younger drivers can’t be bothered getting into the profession anymore. Companies don’t want to hear about the issues, the same goes for governments,” says lorry driver Jason Boden*.

“Drivers from top to bottom are treated with utter disdain, we are second-class citizens.

“A lot of drivers turn to drink to numb the pain, some take drugs. I have known drivers to kill themselves partly because they think there is no way out.”

I have seen a lot of drivers whose mental health is suffering. They are fed up with it now

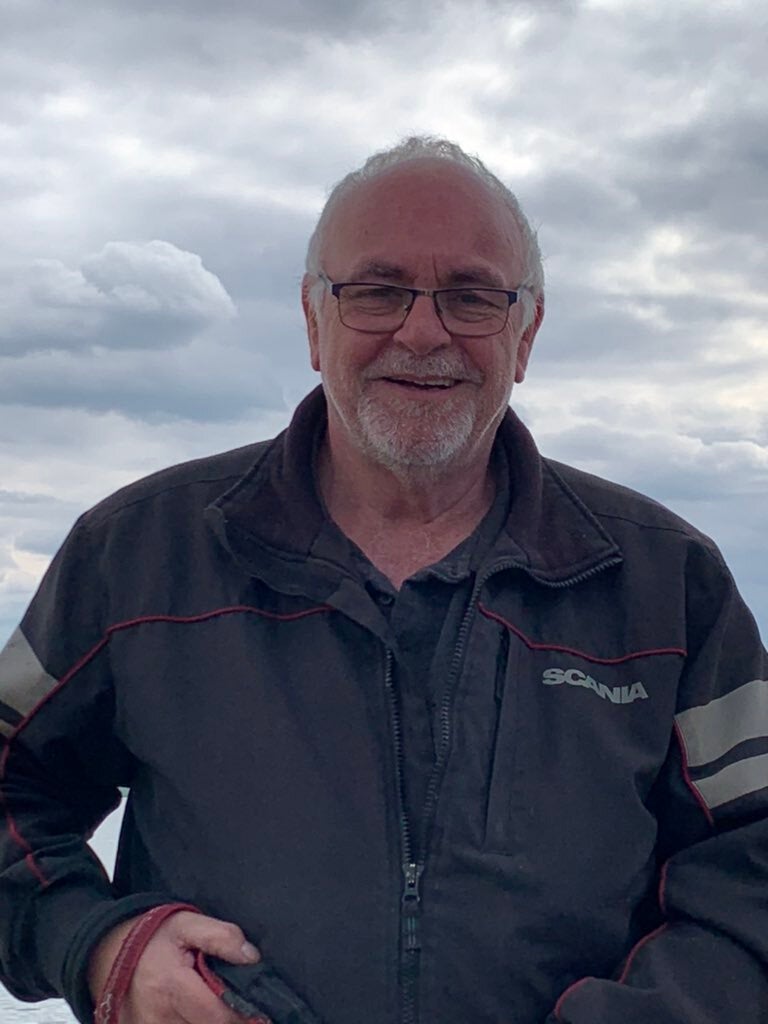

In the queue at Dover, Michael Thompson, a 62-year-old haulier from Lancashire, says there are still almost no local facilities for drivers, despite years of pleas from hauliers and warnings that Brexit would worsen the situation on Kent’s congested roads.

“You’ve got a portaloo if you’re lucky,” he says. “Even when everything’s running OK [through the port], there’s nowhere to park in Kent if you need a driving break because they are putting clamps and giving tickets, for people parking in lay-bys.”

Some facilities elsewhere in the UK “smell like a sewer”, and have no security, meaning drivers often have their fuel stolen. “It’s disgusting”, says Thompson. “I have seen a lot of drivers whose mental health is suffering. They are fed up with it now.”

He says he is considering handing his notice in this week, after more than four decades working in the industry.

“You can be sat there for five, six hours, you just think, ‘I don’t need this, I don’t want to do it any more’. It makes you angry.

“I’m lucky, I don’t drink a lot, but I have seen people turn into drink more and more... just to relax and drop off and have a good night’s sleep or a good day’s sleep, if they’ve been driving at night.

Thompson’s typical day now starts at 7am, when he drives to Heathrow before making a journey to Liege in Belgium, via a couple of stop-offs.

He arrives at 10 or 11pm and beds down in his truck for the night. “You get used to it,” he says. “But I don’t think people understand how hard drivers work, the hours that they do.”

Hours of delays, worsened this year by additional checks brought in at the UK border from 1 January, have pushed some drivers beyond their limits, he says.

Problems with depression in the industry have been flagged for several years. Mental health charity Mind estimated in 2018 that around 30 per cent of absences among hauliers are for stress, depression and anxiety.

Last year, a survey by Haulage Express found that more than half of logistics companies had seen an increase in employee stress, anxiety and other mental health issues which they attributed to the indirect impacts of Brexit.

Other factors have always put drivers at risk: variable shift patterns, disrupted sleep, loneliness and long periods of remaining sedentary.

“It is not a healthy environment,” says Colin Merrick, a lorry driver with 36 years of experience in the industry. “Terrible” facilities that provide only low-quality fast food mean that many drivers are physically unhealthy, he says.

All we are is a pain to everybody on the road, we are seen as a boil on the backside of life

“We drive 44-tonne killing machines. We are professionals, and in Europe we are treated like professionals, but in the UK we aren’t. You don’t even get a cup of coffee at most services here.

“All we are is a pain to everybody on the road, we are seen as a boil on the backside of life.”

As a result, it’s been difficult to attract the right calibre of driver. “The standard has dropped so much over the years,” says Merrick.

The positive side of the shortage of drivers is that pay has jumped, he says. “We are now back up to where we should be.”

Salaries for experienced lorry drivers can be upwards of £50,000 a year, according to trade body Logistics UK. But it has not been enough to attract new blood to the industry, he says.

And the driver shortage has heaped more pressure on what was already a tough job.

“We are now under extreme pressure. Consumers are demanding, they want everything to be available at all times and that means having drivers on the roads 24-7.” says Merrick.

Brexit has made that task significantly more difficult, with worse to come.

“There is a lot of bureaucracy and red tape now for us drivers. I have to check all the relevant paperwork before I go into Calais. It takes longer and longer to do.

“Sometimes the left and right hand aren’t speaking to each other. Something can be checked on one side and it’s fine, you get to the other side and it’s not. The system allows them to just park you up.”

He is highly pessimistic about the industry’s future.

“It’s very difficult to attract new blood to the industry. The facilities are so, so poor. This is not a sexy industry.”

Temporary visas introduced by the government are the equivalent of “putting a band aid over the problem”, says Merrick.

“If you go into any transport cafe, you will see we are an old, grey, bald, fat group of drivers. This industry is heading for an almighty crash. It’s buggered, frankly.”

*Surname has been changed at interviewee’s request

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks