Hamish McRae: America's optimism is fuelled by the Fed's loose monetary policy

Economic View: 'Safe' investments have performed badly while 'risky' ones have performed best

Washington DC. One of the great things about being in the United States is its optimism. I sometimes feel that Americans are more optimistic than they ought to be, whereas we in Britain are more pessimistic than the facts warrant.

Right now, on that crude measure of optimism, share prices, the US is back on top. Last week, both the S&P 500 and the Dow Jones actually topped their previous peaks. If you take consumer comfort, an index calculated by Bloomberg to convey how consumers feel about their finances and other aspects of their lives, that is at a five-year high. Unsurprisingly though, it is the higher income groups that are most optimistic and the lower ones least. It is an "unto those that have" type of recovery, which is only gradually broadening into one that benefits the whole of the country.

This is basically because the main driver of recovery has been the ultra-loose monetary policy of the Federal Reserve. Over the past few days the great debate here in Washington and on Wall Street is how quickly the Fed will tighten policy. There is a clear split on the board, with some members evidently feeling that the risks of not starting to taper off the Fed's monthly purchases of treasury debt this autumn are greater than the risks of starting too soon. Others disagree. These differences reflect a division within the Fed among its officials. There is one debate about how quickly and in response to what economic information it should cut back. There is another about how much guidance the Fed should give about its future policies. Markets want clarity, but the clearer you are about what you might do, the more you close off your options.

There is no road map on what to do because the Fed has never before followed such an expansionary policy, or at least never in peacetime. If you have never done something before, you don't know how to stop it. One thing that does seem clear is that even when the Fed does stop buying treasury debt, interest rates will remain at very low levels for several years. In the medium term that will create other distortions, but in the short-term low interest rates are very good for shares. It was a dovish statement by Fed chairman Ben Bernanke that pushed equities to that new peak last week.

That leads to a wider debate about investment strategy and in particular the case for switching out of fixed-interest securities – US bonds, UK gilts in particular – and into something else. I have been looking at some work by Merrill Lynch, the giant "thundering herd" of brokers now owned by Bank of America. Its message is that the great rotation out of bonds and into equities is well under way and will continue. So far this year US equities and the dollar are up 8 to 9 per cent, while bonds and commodities are down 4 to 6 per cent.

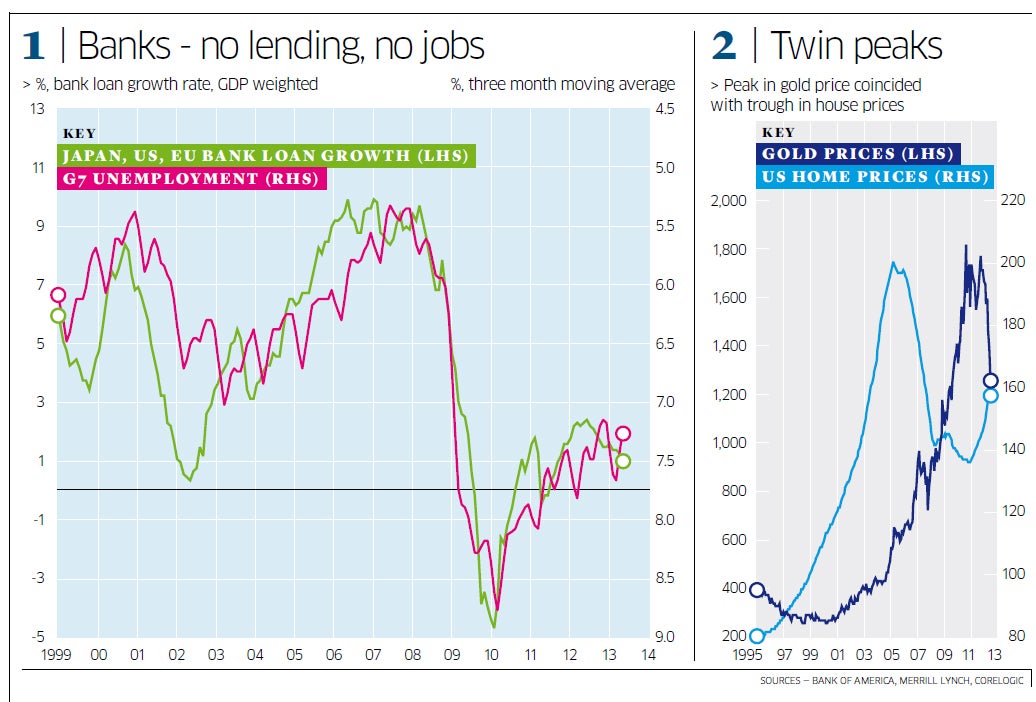

For me, the most interesting point is that what seemed to be "safe" investments have all performed badly, while supposedly "risky" ones have performed best. It is the reverse of the "flight to safety" that characterised much of the past couple of years. In the small graph you can see how the peak of the gold price, gold being the ultimate haven when investors are scared, coincided with the trough in US house prices. Now gold is no longer safe and houses no longer risky.

Merrill Lynch makes a wider point here. It is that many of the safe havens have turned out to be quite the reverse. Thus first gold, then Apple, then bonds, now emerging markets – they have all tumbled. US corporate bonds have had the worst year for total return since 1973. And do you want to know the very best investment over the past year, with a total return of 232.6 per cent? Greek government bonds. What seemed to be most risky has brought the best returns.

So what happens next? Merrill Lynch's general view is that the present combination of high liquidity and low growth that has been supporting share prices will shift to a lower liquidity but higher growth combination. In other words, the bad reason for holding equities (the Fed is printing shedloads of money), will be replaced by the good one (the US economy will put in a stronger growth performance).

Let's hope that is right, for there is a catch. The banks are not lending much money. We are very aware of that in the UK, but I had not fully appreciated that this was as big a concern here in the US. The argument was that the US was growing faster than the UK because it had fixed its banks more swiftly. There is something in that, but the fact remains that if you look at the global supply of credit it is still pretty soft. As you can see from the larger chart there is a clear link between unemployment in the G7 and loan growth in the main industrial countries. Merrill Lynch's argument is that one of the factors holding back job creation is the regulations being imposed on banks. You may say that is special pleading from a bank-owned broker but it is hard to avoid the conclusion that unless banks are allowed to lend more, job creation in the G7 is likely to remain weak. We have to keep our fingers crossed that the UK private sector continues to increase its employment.

In the US, job creation has become perhaps the most watched single indicator, since Fed policy will be determined as much as anything else by the decline in unemployment. Policy has to get back to normal. Until those monthly purchases of debt are stopped the optimism exemplified by the stock market will have a fragile backing. I do love the optimism of America, but I worry about the solidity of the base on which that optimism is built.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies