Hamish McRae: First reactions to the Finance Bill find both God and the devil in the details

Economic Life: Ernst & Young said the bill would encourage the UK's entrepreneurs and provide a launch pad for the small firms that will enable the economy to flourish

Was that Budget really business-friendly? The Finance Bill, published yesterday, gives the details and the accountants have started to pore over it to try to determine whether that expression attributed variously to Mies van der Rohe and Gustave Flaubert – that God is in the detail – duly applies, or whether it is the corrupted version and we are dealing instead with the devil.

The initial reactions have been mixed. Ernst & Young welcomed the proposals for small business, saying the bill "confirmed a bundle of measures aimed at growing the UK's current crop of entrepreneurs and providing a launch pad for generating small to medium-sized enterprises of the future that will be so important to the growth of our economy". It welcomed "reductions in corporate tax rates; the extension of the short life asset definition for capital allowances; and improvements to R&D tax breaks".

The accountants were less than kind, however, about disguised remuneration, noting that the result was "an overly complex and lengthy piece of legislation – having grown from 25 to 59 pages – which still has the potential to capture many unintended situations".

What matters is not what accountants, or indeed companies, say but what companies do. Do they move offshore or not? Do they invest or not? The Budget was welcomed by Sir Martin Sorrell, who indicated that WPP would probably move its headquarters back from Ireland to the UK as a result. But North Sea oil operators are furious – the Energy Secretary, Chris Huhne, was meeting them yesterday – and several of them, most notably the Norwegian firm Statoil, have said they will suspend further investment until they can evaluate the impact of the new tax the Chancellor has imposed.

We will have to see, just as we will have to see whether proposed banking rules will encourage Barclays, HSBC and Standard Chartered to move their headquarters, respectively, to New York, back to Hong Kong, and, probably, to Singapore. If that happened, only the two part-nationalised high street banks, Royal Bank of Scotland and Lloyds, would remain as substantial UK-based banking institutions. The country would still get tax revenue from UK-based activities but the "Wimbledonisation" of British banking would have taken a further leap forward.

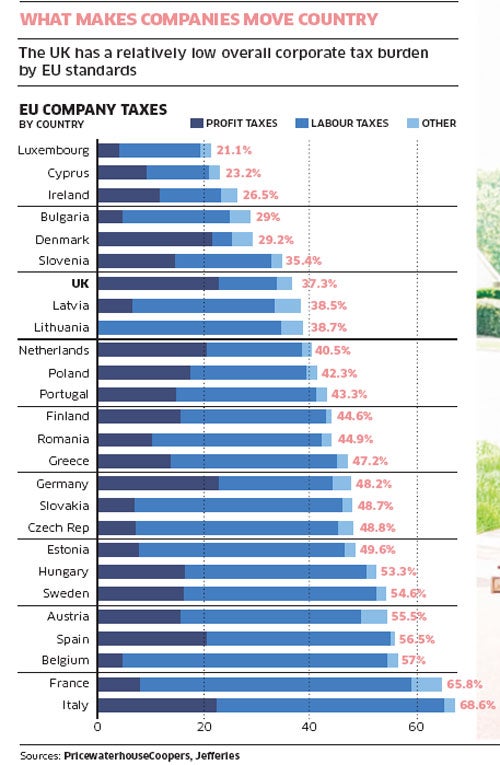

This leads into three wider debates. One is the extent to which countries should use tax as an economic weapon. Ireland has come under the cosh for its 12.5 per cent corporate tax rate, though it is resisting European pressure to change it. But that is not the only tax that businesses have to pay, for they also have labour taxes, business rates and so on. If you add all the different types of taxation together, the picture in Europe varies enormously, ranging as you can see in the chart from little more than 20 per cent in Luxembourg to nearly 70 per cent in Italy. There are, of course, exemptions and most companies do not pay the full headline rates by any means. Headline levels are quite low in the UK – lower than in any of the large EU members.

A second issue is what makes companies move. Tax is one thing but there are many other others. Availability and cost of staff are both crucial. So is the productivity of staff. Infrastructure matters. Political stability matters. And there are costs to moving, so decisions are inevitably based on medium-term assessments of the attractiveness or otherwise of any particular jurisdiction. I suppose the danger arises not so much from companies moving existing operations wholesale, but rather from how they place their future investments: where they expand and where they retreat.

And a third issue is what, in an increasingly mobile world, countries can reliably tax. Some people and some types of business are more mobile than others. You cannot move a steel plant but you can move a hedge fund. You cannot move property, and that may become a more important source of revenue to governments. Spending is easier to tax than income, particularly if the latter comes from multiple sources. And so on. The good news (at least for governments) is that the so-called "race to the bottom", whereby governments are forced to cut rates and get less and less revenue as their tax base is eroded, has not happened.

We will have to wait and see what companies do in response to the Finance Bill. Don't expect anything sudden, except possibly in the case of the North Sea. When, a couple of decades ago, Norway jacked up its tax rates on its sector of the North Sea, companies moved their exploration rigs to British waters; you can't move the oil but you can change where to look for it. You can also change the amount of extra investment you put in to extract the marginal output.

Simplification is good and the proposals on pensions have been welcomed by the National Association of Pension Funds – remember that providing pensions is a major cost on businesses. But I don't think the Coalition should kid itself that it has won back much trust yet. After the tax and regulatory upheavals of the past couple of years Britain remains a less certain place in which to do business than it was 10 or 20 years ago. Watch what companies do, not what they say – and likewise what governments do.

Ireland's sorry saga could be nearly over

The other significant business news yesterday came in the form of the results of the bank stress tests in Ireland. The difficulties of the Irish banking sector have emerged in such a drawn-out way and there have been so many false dawns that it is hard to say with confidence that this sad tale is now moving towards a close. But it does feel that way. Once a market hits a bottom, things can flip round quite fast. That goes for Irish property but it also goes for Irish bonds, not just bank bonds and government bonds but other fixed-interest securities too.

The detail here is hugely important. We are going to hear the word "haircut" a great deal in the coming days, the issue being which bondholders of what seniority get their money back in full. A haircut means they don't. This is about the value of a government guarantee. I was in Ireland earlier this week and a wise financier said to me that what the government should have done was to guarantee Bank of Ireland and Allied Irish Banks, the two big established banks, but not the newcomer, Anglo Irish. "We all knew they were cowboys," he said.

Maybe. We have to wait and see how this develops but there is, I think, a natural cycle to financial disruption. This does not go on for ever and whatever it is – a property crash, a Third World debt default, a company going bust – there is a resolution. A couple of years from now at the latest, probably sooner, Ireland will have reached a resolution and these events will be seen as an important step towards that.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks